Cholangiocarcinome

Le cholangiocarcinome (de chol du gr. χολή : « bile », angi(o) du gr. ἀγγαιον : « capsule, vaisseau » et carcinome du gr. καρκίνωμα : « cancer ») est une tumeur développée à partir de l'épithélium tapissant les voies biliaires. Il peut entraîner une obstruction des voies biliaires, et provoquer l'apparition d'une cholestase. Les symptômes cliniques sont essentiellement ceux provoqués par l'atteinte de la fonction hépatique.

| Médicament | Évérolimus et régorafénib |

|---|---|

| Spécialité | Oncologie |

| CIM-10 | C22.1 |

|---|---|

| CIM-9 | 155.1, 156.1 |

| ICD-O | 8160/3 |

| OMIM | 615619 |

| DiseasesDB | 2505 |

| MedlinePlus | 000291 |

| eMedicine | 277393 |

| MeSH | D018281 |

| Patient UK | Cholangiocarcinoma |

![]() Mise en garde médicale

Mise en garde médicale

C'est un cancer relativement rare. Son pronostic est mauvais et son évolution rapide. Sa prévalence et la mortalité dont il est cause augmentent depuis quelques décennies sans que l'on puisse en déterminer les raisons[1] - [2]. Les causes et facteurs de risques incluent des formes associées à des parasitoses (souvent en Asie du Sud-Est), les nitrosamines, les dioxines, le thorotrast (dioxyde de thorium en solution injectable), le radon[3] et peut-être l'absorption d'amiante via la nourriture et/ou la boisson (alors notamment retrouvée dans le système digestif et des nodules cancéreux du système biliaire)[4] - [5] - [6].

Le traitement classique d'un cholangiocarcinome consiste en une ablation chirurgicale de la tumeur, un traitement par chimiothérapie anticancéreuse, voire en une approche palliative.

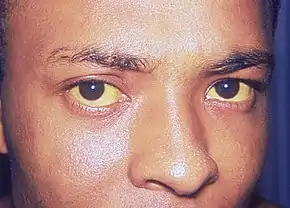

Signes et symptômes

Les signes les plus courants de cholangiocarcinome sont une perturbation du bilan sanguin hépatique due à un fonctionnement anormal du foie (détectable lors du dosage notamment de la bilirubine, l'ASAT, l'ALAT, des phosphatases alcalines et de la gGT), un ictère (communément appelé jaunisse) s'accompagnant de démangeaisons (près de 66 % des cas), des douleurs abdominales (dans 30 % à 50 % des cas). On retrouve un changement de couleur des fèces qui se décolorent à cause de l'absence d'évacuation des sels biliaires vers le tube digestif. Ces derniers sont éliminés par l'urine qui devient alors plus sombre. Une altération de l'état général accompagne de nombreuses tumeurs comme le cholangiocarcinome avec fatigue, anorexie et perte de poids (dans 30 % à 50 % des cas). Dans certains cas, il est détecté de la fièvre (environ 20 % des cas)[7] - [8].

Au-delà de ces signes classiques, les symptômes dépendent de la localisation de la tumeur : les patients avec un cholangiocarcinome des voies biliaires extra-hépatiques (en dehors du foie) sont davantage sujets à un ictère tandis que ceux avec une tumeur des voies biliaires hépatiques (à l'intérieur du foie) présentent souvent des douleurs latéralisées du côté droit de l'abdomen sans signe de jaunisse ni décoloration des selles[9].

Les dosages sanguins des fonctions hépatiques (bilirubine, ASAT, ALAT, etc.) révèlent fréquemment des niveaux élevés de bilirubine, de phosphatase alcaline et de gamma glutamyl transpeptidase (gGT) et des niveaux relativement normaux des transaminases (ALAT & ASAT). De tels résultats indiquent une obstruction des voies biliaires (plus qu'une infection ou une inflammation du foie) comme cause principale de l'ictère par cholestase[10]. Un marqueur biologique tumoral comme l'antigène CA 19.9 présente un taux sanguin élevé dans la majorité des cas.

Épidémiologie

| Pays | IC (hommes/femmes) | EC (hommes/femmes) |

|---|---|---|

| États-Unis | 0.60 / 0.43 | 0.70 / 0.87 |

| Japon | 0.23 / 0.10 | 5.87 / 5.20 |

| Australie | 0.70 / 0.53 | 0.90 / 1.23 |

| Angleterre + pays de Galles | 0.83 / 0.63 | 0.43 / 0.60 |

| Écosse | 1.17 / 1.00 | 0.60 / 0.73 |

| France | 0.27 / 0.20 | 1.20 / 1.37 |

| Italie | 0.13 / 0.13 | 2.10 / 2.60 |

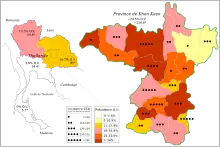

Le cholangiocarcinome est un cancer dont la fréquence est la plus élevée en Asie, notamment à Hong Kong et en Thaïlande, a priori en raison de parasitoses endémiques de ces régions. Il semble 6 fois plus fréquent aux États-Unis — où il touche plus particulièrement les Amérindiens —qu'en France[12] : on en compte environ 2 000 nouveaux cas par an en France[13] (importante augmentation au cours des dernières décennies) et 12 000 aux États-Unis en 2009, la moitié concernant la vésicule biliaire, les deux derniers quarts se répartissant entre voies biliaires intra- et extra-hépatiques[14]. La prévalence (nombre total de malades dans une population générale) varie selon les pays.

De nombreuses études ont montré une augmentation du nombre de cas au fil des années, pour des raisons encore inconnues[1].

Facteurs de risque

Bien que dans la plupart des cas, aucun facteur de risque particulier ne soit trouvé chez les patients atteints de cholangiocarcinome, on distingue plusieurs facteurs favorisant l'apparition de ce cancer.

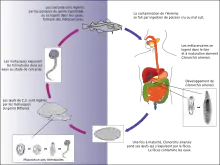

L'angiocholite sclérosante, une maladie inflammatoire rare des canaux biliaires, est communément associée à cette tumeur en Occident[15] - [16] - [17] alors que diverses parasitoses du foie comme la distomatose à Opisthorchis viverrini où l'homme se contamine en mangeant du poisson cru, ou à Clonorchis sinensis sont fréquemment associées en Orient[18] - [19] - [20] - . Le mécanisme de l'effet cancérigène a été mis en évidence en 2009 avec la découverte de la granuline Ov-GRN-1, un facteur de croissance produit par le parasite capable d'induire la prolifération des cellules de l'hôte[21].

Prévalence du cholangiocarcinome et d'Opisthorchis viverrini en Thaïlande entre 1990 et 2001.

Le cholangiocarcinome est aussi associé à des maladies chroniques du foie, que ce soient les hépatites virales[22] - [23] - [24] ou les cirrhoses[25], ou la surcharge en fer pour les formes intrahépatiques. Le VIH a également été mis en cause dans une étude mais il est possible que ce soit en réalité l'augmentation du risque d'infection par le virus de l'hépatite C chez les patients séropositifs qui favorise l'apparition de cholangiocarcinomes[26].

Des pathologies congénitales du foie peuvent se compliquer. La maladie de Caroli, une pathologie héréditaire rare consistant en une dilatation des voies biliaires intra-hépatiques, ou les kystes congénitaux du cholédoque ont été associées à un risque élevé (15 % sur la vie entière) de développer cette tumeur[27] - [28]. D'autres kystes comme les microhamartomes biliaires (MHB) ont été également mis en cause[29] (ils sont également appelés complexes de von Meyenburg[30]). Le syndrome de Lynch et la papillomatose des voies biliaires, tumeur rare avec obstruction à répétition des voies biliaires, sont également soupçonnés de favoriser les cholangiocarcinomes[31] - [32].

Les calculs intra-hépatiques, rares en Occident mais courants en Asie, sont suspectés d'être des éléments à risque de cholangiocarcinome[33] - [34] - [35].

L'usage de Thorotrast, ancien produit de contraste en radiodiagnostic et substance cancérogène, a été incriminé dans la survenue de ce cancer[36] - [37] de même que l'exposition à la dioxine[38].

Physiopathologie

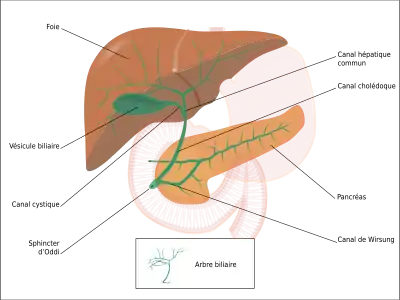

- Schéma 3 :

Arbre biliaire avec ses différentes voies.

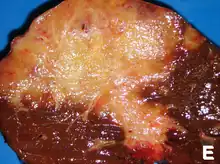

Le cholangiocarcinome peut affecter n'importe quelle zone des voies biliaires, qu'elles soient à l'intérieur du foie dites intra-hépatiques ou à l'extérieur dites extra-hépatiques. Les tumeurs apparaissant à l'endroit où les voies biliaires sortent du foie sont appelées péri-hilaires. Un cholangiocarcinome situé à la jonction où les voies biliaires intra-hépatiques droite et gauche se rencontrent pour former le canal hépatique commun est parfois nommé tumeur de Klatskin[39].

Bien que le cholangiocarcinome soit connu pour être un adénocarcinome des cellules épithéliales des voies biliaires, les cellules où il prend son origine sont inconnues. Néanmoins, des indices récents pointent vers des cellules souches (pluripotentes) du foie[40] - [41] - [42]. On pense que le cancer se développe à travers des séries de stades — depuis l'hyperplasie précoce et la métaplasie, en passant par la dysplasie, jusqu'au développement du carcinome proprement dit — en un processus similaire à celui du cancer du côlon[43]. L'inflammation chronique et l'obstruction des conduits biliaires, et le flux de bile pathologique en résultant, sont considérés comme jouant un rôle dans cette progression[43] - [44] - [45]. Une autre hypothèse serait liée au biofilm formé en particulier par Salmonella typhi[46] - [47] - [48].

Histologiquement, ces tumeurs peuvent varier d'indifférenciées à bien différenciées.

Diagnostic

Le cholangiocarcinome est diagnostiqué histologiquement par l'examen des tissus retirés lors d'un acte chirurgical ou après une biopsie de la tumeur. On peut soupçonner sa présence chez un patient avec un ictère à bilirubine conjuguée obstruant les voies biliaires. Le considérer comme élément de diagnostic en cas d'angiocholite sclérosante (ou cholangite sclérosante primitive) est difficile car, si de tels patients ont un fort risque de développer un cholangiocarcinome, les symptômes sont, par contre, difficiles à distinguer de ceux de l'angiocholite. De plus, chez ces patients, les indices diagnostiques (masse visible à l'imagerie ou dilatation des voies biliaires) peuvent ne pas être évidents. La protéomique des tissus et du sérum, qui, associée aux techniques de désorption-ionisation laser assistée par matrice (SELDI-TOF MS), semble prometteuse pour identifier de potentiels marqueurs biologiques moléculaires spécifiques du cholangiocarcinome et devrait permettre d'améliorer le diagnostic[49].

Tests sanguins

Il n'existe pas d'examen spécifique lié à une prise de sang qui puisse diagnostiquer le cholangiocarcinome par lui-même. Les taux sanguin d'antigène carcino-embryonnaire (ACE en français ou CEA en anglais) et ceux de CA 19.9 sont généralement élevés, mais ne sont pas assez sensibles ou spécifiques pour être utilisés comme un outil de dépistage. En effet, des taux élevés de ces marqueurs se notent dans d'autres maladies du tube digestif, de même tous les cholangiocarcinomes ne s'accompagnent pas d'une élévation de ces taux de marqueurs. Toutefois, les dosages d'ACE et de CA 19.9 peuvent venir en complément des techniques d'imagerie pour soutenir un diagnostic de cholangiocarcinome[50] et aider au suivi thérapeutique.

Imagerie abdominale

L'échographie du foie et des voies biliaires est souvent utilisée comme première méthode d'imagerie auprès des patients chez qui l'on suspecte un ictère (jaunisse) obstructif[51] - [52]. Cette forme d'imagerie peut identifier l'obstruction et/ou une dilatation biliaire, ce qui, dans certains cas, peut s'avérer suffisant pour diagnostiquer un cholangiocarcinome[53]. On peut aussi utiliser l'écho-endoscopie qui permet l'ablation des polypes de petite taille avant leur transformation en carcinome[54] - [55]. Le scanner tomodensitométrique peut aussi donner des informations diagnostiques du cholangiocarcinome[56] - [57] - [58]. La précision du diagnostic par tomodensitométrie est satisfaisante mais peut induire une sous-estimation de la dissémination de la tumeur dans les voies biliaires[59].

Imagerie des voies biliaires

Bien que l'imagerie non invasive abdominale puisse se révéler utile dans l'établissement du diagnostic, l'imagerie locale des voies biliaires s'avère souvent nécessaire. La cholangio-pancréatographie rétrograde par voie endoscopique (CPRE, ou en anglais ERCP — ou cathétérisme endoscopique bilio-pancréatique) est une procédure combinant l'endoscopie et la fluoroscopie réalisée par un gastro-entérologue ou un chirurgien, largement utilisée dans ce but.

Bien qu'invasive et présentant des risques per- et post-opératoires (développement de pancréatite dans 5 % des cas, risques classiques inhérents à l'endoscopie), elle présente l'avantage de permettre un brossage pour examen cytologique, d'obtenir une biopsie et de placer un stent ou de procéder à d'autres interventions pour éliminer l'obstruction biliaire (dilatation des voies biliaires ou lyse d'une éventuelle lithiase)[10]. Une échographie endoscopique peut aussi être réalisée en même temps[60]. L'IRM au niveau pancréatique et biliaire est une alternative non-invasive à l'ERCP[61] - [62] - [63]. Certains auteurs ont suggéré que l'IRM pourrait supplanter l'ERCP dans le diagnostic des cancers biliaires[64] - [65] - [66] - [67].

Chirurgie

Une méthode de chirurgie exploratoire comme une cœlioscopie peut être utilisée pour déterminer le stade d'évolution de la tumeur (qui permet d'éviter des techniques plus invasives comme la laparotomie)[68] - [69]. En traitement du stade précoce, la chirurgie est également le seul traitement permettant la guérison ou rémission[70].

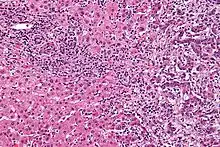

Histologie

Les cholangiocarcinomes sont en général bien différenciés ou modérément différenciés. L'immunohistochimie se révèle utile dans le diagnostic pour différencier les tumeurs primitives des métastases originaires d'autres tumeurs hépato-intestinales[71]. L'intégrine αvβ6 est un bon marqueur immunohistochimique (spécificité : 100 % ; sensibilité 86 % ; meilleur que CK7, CK20, et HepPar 1) pour confirmer un diagnostic de cholangiocarcinome (par rapport à ceux de carcinome hépatocellulaire ou d'autres carcinomes)[72].

Traitement

Le traitement du cholangiocarcinome consiste en différentes modalités, tant chirurgicales, que médicales, et n'exclut pas l'approche par les soins palliatifs devant une évolution létale rapide.

Drainage biliaire

Les cholangiocarcinomes sont souvent responsables d’obstruction des voies biliaires et donc du développement d'un ictère. La prise en charge débute donc souvent par la pose d'un drain biliaire soit en remontant le long des voies biliaires (CPRE) soit par voie transcutanée.

Chirurgie

Considéré comme de pronostic sévère si l'ablation des tumeurs n'est pas totale, cette maladie se traitera donc essentiellement par la chirurgie[70]. L'opérabilité de la tumeur est souvent difficile à déterminer[73] et en particulier tient compte de l'extension biliaire (classification de Bismuth[74]). L'exérèse doit être prioritaire par rapport à tout traitement symptomatique (notamment en cas d'ictère où l'objectif de régression de l'ictère ne doit pas retarder le traitement chirurgical). En règle générale, la résection est possible essentiellement en cas de localisation sur la vésicule biliaire ou sur les voies biliaires extra-hépatiques. Elle est beaucoup plus rarement faisable en cas d'atteinte des voies biliaires intra hépatiques.

Dans le cas d'un cholangiocarcinome intra-hépatique, une hépatectomie partielle mais large est souvent requise. Celle-ci doit laisser un foie d'une taille suffisante (il doit rester plus de 0,5 % du poids corporel en foie sain[75]) pour qu'il puisse se régénérer tout en supprimant complètement la tumeur[76] - [77]. Il existe de nombreuses contre-indications à une opération aussi complexe. Les résultats de ce type d'acte (et les facteurs ayant de l'influence sur ceux-ci) restent incertains mais montrent une amélioration du taux de survie à un, trois et cinq ans[78].

Chimiothérapie et radiothérapie post-opératoire

Si la tumeur peut-être retirée par chirurgie, les patients peuvent recevoir une chimiothérapie adjuvante ou une radiothérapie après l'opération pour améliorer les chances de guérison. Ce traitement est d'effet incertain dans la littérature médicale : des résultats tant positifs[79] - [80] que négatifs[9] - [81] - [82] - [83] ont été rapportés.

Transplantation hépatique

Longtemps controversée (100 % de récidive dans les premières études), la transplantation hépatique semble prometteuse et plusieurs équipes chirurgicales font état de survies à 5 ans entre 30 et 40 % dans le cholangiocarcinome du hile[84]. Compte tenu de la pénurie de greffons, certains auteurs considèrent que ce taux est trop faible pour s'orienter vers cette solution thérapeutique[85].

Traitement des cas à un stade avancé

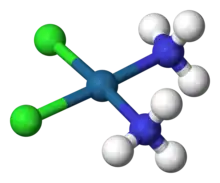

La chimiothérapie est dans ce cas utilisée pour améliorer la qualité de vie des patients[86]. Il n'existe pas une chimiothérapie universelle dans ce cas (produits utilisés : 5-fluorouracile avec de l'acide folinique[87], gemcitabine[88], ou gemcitabine plus cisplatine[89] irinotecan[90], ou capécitabine[91], une petite étude a suggéré un possible bénéfice de l'erlotinib, inhibiteur de la tyrosine kinase chez les patients avec un cholangiocarcinome avancé[92]). Une étude britannique de 2010 a montré l'intérêt d'associer deux produits, le cisplatine et le gemcitabine, en première intention dans les cholangiocarcinomes non opérables[93].

Une étude récente (2021), multicentrique, randomisée, ouverte, de phase 2b, a conclu qu'un traitement par irinotécan (liposomal) en seconde ligne (en ajout au traitement classique de deuxième ligne par fluorouracil plus leucovorine dans cette étude), améliore les chances de survie en phase métastatique du cancer des voies biliaires[94].

Pronostic

Cancer considéré comme de mauvais pronostic parmi les tumeurs hépatiques, son traitement par tumorectomie offre la seule chance de guérison complète (mais sans garantie[95]). Dans le cas de tumeurs non opérables, le taux de survie à cinq ans est très peu encourageant, notamment en cas de localisations secondaires dans les ganglions lymphatiques[96]. Il est inférieur à 5 % dans le cas de métastases[97]. En l'absence de traitement, l'espérance de vie est réduite à seulement six mois[98].

Dans les cas opérables, la probabilité d'une guérison complète varie en fonction de la localisation et de la difficulté à retirer la tumeur. Pour un cholangiocarcinome résécable, les facteurs de mauvais pronostic sont[70] :

- une albuminémie abaissée en préopératoire ;

- la présence de résidu tumoral sur la tranche de section opératoire (la tumeur n'a été que partiellement enlevée) ;

- le stade TNM (T-stage : taille de la tumeur primitive).

Il semble exister une corrélation entre l'expression des marqueurs souches EpCAM et CD44 au niveau du stroma tumoral et dans le tissu fibreux du foie « sain » péri-lésionnel ainsi que le risque de récidive[99].

Différents stades

Bien qu'il y ait au moins trois stades dans l'évolution du cholangiocarcinome, aucun ne permet de prédire les chances de survie du patient[100]. La donnée la plus importante liée aux stades est l'opérabilité ou la non-opérabilité de la tumeur. Souvent, cette information n'est obtenue que lors de l'acte chirurgical lui-même[10].

Les directives générales concernant l'opérabilité incluent[101] - [102] :

- l'absence de ganglion lymphatique ou de métastases du foie ;

- l'absence d'implication de la veine porte ;

- l'absence de prolifération dans les organes adjacents ;

- l'absence de pathologie métastatique étendue.

En 2009, plusieurs études retrouvent un pourcentage de survie de 20 %, à 5 ans, chez des patients opérés[103] (32 % dans une étude de 2007 sur les cholangiocarcinomes périphériques opérables[104]).

Notes et références

- Études indépendantes ayant observé une augmentation ininterrompue de l'incidence du cholangiocarcinome dans le monde :

- (en) T. Patel, « Worldwide trends in mortality from biliary tract malignancies », BMC Cancer, vol. 2, , p. 10. (PMID 11991810, DOI 10.1186/1471-2407-2-10)

- (en) T. Patel, « Increasing incidence and mortality of primary intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States », Hepatology, vol. 33, no 6, , p. 1353–7. (PMID 11391522, DOI 10.1053/jhep.2001.25087)

- (en) Y. Shaib, J. Davila, K. McGlynn, H. El-Serag, « Rising incidence of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States: a true increase? », J Hepatol, vol. 40, no 3, , p. 472-7. (PMID 15123362, DOI 10.1016/j.jhep.2003.11.030)

- (en) J. West, H. Wood, R. Logan, M. Quinn, G. Aithal, « Trends in the incidence of primary liver and biliary tract cancers in England and Wales 1971–2001 », British Journal of Cancer, vol. 94, no 11, , p. 1751-8. (PMID 16736026, DOI 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603127)

- (en) S. Khan, S. Taylor-Robinson, M. Toledano, A. Beck, P. Elliott, H. Thomas, « Changing international trends in mortality rates for liver, biliary and pancreatic tumours », J Hepatol, vol. 37, no 6, , p. 806-13. (PMID 12445422, DOI 10.1016/S0168-8278(02)00297-0)

- (en) T. Welzel, K. McGlynn, A. Hsing, T. O'Brien, R. Pfeiffer, « Impact of classification of hilar cholangiocarcinomas (Klatskin tumors) on the incidence of intra- and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States », J Natl Cancer Inst, vol. 98, no 12, , p. 873–5. (PMID 16788161)

- Patel T (2001). Increasing incidence and mortality of primary intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States. Hepatology, 33(6), 1353-1357.

- Mosconi S, Beretta G.D, Labianca R, Zampino M.G, Gatta G & Heinemann V (2009). Cholangiocarcinoma. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology, 69(3), 259-270.

- Frumkin H & Berlin J (1988). Asbestos Exposure and Gastrointestinal Malignancy Review and Meta‐Analysis. American journal of industrial medicine, 14(1), 79-95|résumé.

- Szendröi, M., Németh, L., & Vajta, G. (1983). Asbestos bodies in a bile duct cancer after occupational exposure. Environmental research, 30(2), 270-280|résumé.

- Brandi, G., Di Girolamo, S., Farioli, A., de Rosa, F., Curti, S., Pinna, A. D., ... & Mattioli, S. (2013). Asbestos: a hidden player behind the cholangiocarcinoma increase? Findings from a case–control analysis. Cancer Causes & Control, 24(5), 911-918.

- (en) D. Nagorney, J. Donohue, M. Farnell, C. Schleck, D. Ilstrup, « Outcomes after curative resections of cholangiocarcinoma », Arch Surg, vol. 128, no 8, , p. 871–7 ; discussion 877–9. (PMID 8393652)

- (en) Bile duct cancer: cause and treatment

- (en) A. Nakeeb, H. Pitt, T. Sohn, J. Coleman, R. Abrams, S. Piantadosi, R. Hruban, K. Lillemoe, C. Yeo, J. Cameron, « Cholangiocarcinoma. A spectrum of intrahepatic, perihilar, and distal tumors », Ann Surg, vol. 224, no 4, , p. 463–73 ; discussion 473–5. (PMID 8857851, DOI 10.1097/00000658-199610000-00005)

- (en) Mark Feldman (éditeur), Lawrence S. Friedman (éditeur) et Lawrence J. Brandt (éditeur), Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease, Saunders, édité chez Elsevier, 8e éd. (ISBN 978-1-4160-0245-1), p. 1493–1496

- (en) S. Khan, S. Taylor-Robinson, M. Toledano, A. Beck, P. Elliott, H. Thomas, « Changing international trends in mortality rates for liver, biliary and pancreatic tumours », J Hepatol, vol. 37, no 6, , p. 806–13. (PMID 12445422, DOI 10.1016/S0168-8278(02)00297-0)

- « Tumeurs de la vésicule biliaire et des voies biliaires - Troubles hépatiques et biliaires », sur Édition professionnelle du Manuel MSD (consulté le )

- C. Housset, Épidémiologie, facteurs de risque et mécanismes de la carcinogenèse biliaire, La Lettre de l'hépato-gastroentérologue; 2007;10(8):181-4.

- (en) A. Jemal, R. Siegel, E. Ward, Y. Hao, J. Xu, M. J. Thun, « Cancer statistics, 2009 », CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:225-49.

- (en) R. Chapman, « Risk factors for biliary tract carcinogenesis », Ann Oncol, vol. 10 Suppl 4, , p. 308–11. (PMID 10436847)

- Études épidémiologiques portant sur l'incidence du cholangiocarcinome chez les personnes avec une cholangite sclérosante primitive :

- (en) A. Bergquist, A. Ekbom, R. Olsson, D. Kornfeldt, U. Broomé et al., « Hepatic and extrahepatic malignancies in primary sclerosing cholangitis », J Hepatol, vol. 36, no 3, , p. 321–7. (PMID 11867174, DOI 10.1016/S0168-8278(01)00288-4)

- (en) A. Bergquist, H. Glaumann, B. Persson, U. Broomé, « Risk factors and clinical presentation of hepatobiliary carcinoma in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis: a case-control study », Hepatology, vol. 27, no 2, , p. 311-6. (PMID 9462625, DOI 10.1002/hep.510270201)

- (en) K. Burak, P. Angulo, T. Pasha, K. Egan, J. Petz, K. Lindor, « Incidence and risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma in primary sclerosing cholangitis », Am J Gastroenterol, vol. 99, no 3, , p. 523-6. (PMID 15056096, DOI 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04067.x)

- (en) C. Rosen, D. Nagorney, R. Wiesner, R. Coffey, N. LaRusso, « Cholangiocarcinoma complicating primary sclerosing cholangitis », Ann Surg, vol. 213, no 1, , p. 21-5. (PMID 1845927, DOI 10.1097/00000658-199101000-00004)

- (en) P. Watanapa, « Cholangiocarcinoma in patients with opisthorchiasis », Br J Surg, vol. 83, no 8, , p. 1062–64. (PMID 8869303, DOI 10.1002/bjs.1800830809)

- (en) P. Watanapa, W. Watanapa, « Liver fluke-associated cholangiocarcinoma », Br J Surg, vol. 89, no 8, , p. 962–70. (PMID 12153620, DOI 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02143.x)

- (en) H. Shin, C. Lee, H. Park, S. Seol, J. Chung, H. Choi, Y. Ahn, T. Shigemastu, « Hepatitis B and C virus, Clonorchis sinensis for the risk of liver cancer: a case-control study in Pusan, Korea », Int J Epidemiol, vol. 25, no 5, , p. 933–40. (PMID 8921477, DOI 10.1093/ije/25.5.933)

- (en) M. J. Smout, T. Laha, J. Mulvenna, B. Sripa, S. Suttiprapa, A. Jones, P. J. Brindley, A. Loukas, « A Granulin-Like Growth Factor Secreted by the Carcinogenic Liver Fluke, Opisthorchis viverrini, Promotes Proliferation of Host Cells », PLoS Pathogens, (DOI 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000611, lire en ligne)

- (en) M. Kobayashi, K. Ikeda, S. Saitoh, F. Suzuki, A. Tsubota, Y. Suzuki, Y. Arase, N. Murashima, K. Chayama, H. Kumada, « Incidence of primary cholangiocellular carcinoma of the liver in Japanese patients with hepatitis C virus-related cirrhosis », Cancer, vol. 88, no 11, , p. 2471-7. (PMID 10861422, DOI 10.1002/1097-0142(20000601)88:11<2471::AID-CNCR7>3.0.CO;2-T)

- (en) S. Yamamoto, S. Kubo, S. Hai, T. Uenishi, T. Yamamoto, T. Shuto, S. Takemura, H. Tanaka, O. Yamazaki, K. Hirohashi, T. Tanaka, « Hepatitis C virus infection as a likely etiology of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma », Cancer Sci, vol. 95, no 7, , p. 592–5. (PMID 15245596, DOI 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb02492.x)

- (en) H. Lu, M. Ye, S. Thung, S. Dash, M. Gerber, « Detection of hepatitis C virus RNA sequences in cholangiocarcinomas in Chinese and American patients », Chin Med J (Engl), vol. 113, no 12, , p. 1138–41. (PMID 11776153)

- (en) H. Sorensen, S. Friis, J. Olsen, A. Thulstrup, L. Mellemkjaer, M. Linet, D. Trichopoulos, H. Vilstrup, J. Olsen, « Risk of liver and other types of cancer in patients with cirrhosis: a nationwide cohort study in Denmark », Hepatology, vol. 28, no 4, , p. 921–5. (PMID 9755226, DOI 10.1002/hep.510280404)

- (en) Y. Shaib, H. El-Serag, J. Davila, R. Morgan, K. McGlynn, « Risk factors of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States: a case-control study », Gastroenterol, vol. 128, no 3, , p. 620–6. (PMID 15765398, DOI 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.12.048)

- (en) P. Lipsett, H. Pitt, P. Colombani, J. Boitnott, J. Cameron, « Choledochal cyst disease. A changing pattern of presentation », Ann Surg, vol. 220, no 5, , p. 644–52. (PMID 7979612, DOI 10.1097/00000658-199411000-00007)

- (en) M. Dayton, W. Longmire, R. Tompkins, « Caroli's Disease: a premalignant condition? », Am J Surg, vol. 145, no 1, , p. 41–8. (PMID 6295196, DOI 10.1016/0002-9610(83)90164-2)

- L. Droy, C. Sagan, J. Paineau, J. Gournay, J. F. Mosnier, « Cholangiocarcinomes sur syndrome des microhamartomes biliaires multiples », Annales de pathologie, vol. 29, no 1, , p. 24-7. (PMID 19233090, résumé)

- Cholangiocarcinome sur complexes de von Meyenburg au cours d'une hémochromatose

- (en) J. Mecklin, H. Järvinen, M. Virolainen, « The association between cholangiocarcinoma and hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal carcinoma », Cancer, vol. 69, no 5, , p. 1112–4. (PMID 1310886)

- (en) S. Lee, M. Kim, S. Jang, M. Song, K. Kim, H. Kim, D. Seo, D. Song, E. Yu, Y. Min, « Clinicopathologic review of 58 patients with biliary papillomatosis », Cancer, vol. 100, no 4, , p. 783–93. (PMID 14770435, DOI 10.1002/cncr.20031)

- (en) C. Lee, C. Wu, G. Chen, « What is the impact of coexistence of hepatolithiasis on cholangiocarcinoma? », J Gastroenterol Hepatol, vol. 17, no 9, , p. 1015–20. (PMID 12167124, DOI 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2002.02779.x)

- (en) C. Su, Y. Shyr, W. Lui, F. P'Eng, « Hepatolithiasis associated with cholangiocarcinoma », Br J Surg, vol. 84, no 7, , p. 969–73. (PMID 9240138, DOI 10.1002/bjs.1800840717)

- (en) F. Donato, U. Gelatti, A. Tagger, M. Favret, M. Ribero, F. Callea, C. Martelli, A. Savio, P. Trevisi, G. Nardi, « Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and hepatitis C and B virus infection, alcohol intake, and hepatolithiasis: a case-control study in Italy », Cancer Causes Control, vol. 12, no 10, , p. 959–64. (PMID 11808716, DOI 10.1023/A:1013747228572)

- (en) D. Sahani, S. Prasad, K. Tannabe, P. Hahn, P. Mueller, S. Saini, « Thorotrast-induced cholangiocarcinoma: case report », Abdom Imaging, vol. 28, no 1, , p. 72–4. (PMID 12483389, DOI 10.1007/s00261-001-0148-y)

- (en) A. Zhu, G. Lauwers, K. Tanabe, « Cholangiocarcinoma in association with Thorotrast exposure », J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg, vol. 11, no 6, , p. 430–3. (PMID 15619021, DOI 10.1007/s00534-004-0924-5)

- Xavier Causse, « Diagnostic et prise en charge du cholangiocarcinome », paragraphe Étiologie

- (en) G. Klatskin, « Adenocarcinoma Of The Hepatic Duct At Its Bifurcation Within The Porta Hepatis. An Unusual Tumor With Distinctive Clinical And Pathological Features », American Journal of Medicine, vol. 38, , p. 241–56. (PMID 14256720, DOI 10.1016/0002-9343(65)90178-6)

- (en) T. Roskams, « Liver stem cells and their implication in hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma », Oncogene, vol. 25, no 27, , p. 3818–22. (PMID 16799623, DOI 10.1038/sj.onc.1209558)

- (en) C. Liu, J. Wang, Q. Ou, « Possible stem cell origin of human cholangiocarcinoma », World J Gastroenterol, vol. 10, no 22, , p. 3374–6. (PMID 15484322)

- (en) S. Sell, H. Dunsford, « Evidence for the stem cell origin of hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma », American Journal of Pathology, vol. 134, no 6, , p. 1347–63. (PMID 2474256)

- (en) A. Sirica, « Cholangiocarcinoma: molecular targeting strategies for chemoprevention and therapy », Hepatology, vol. 41, no 1, , p. 5–15. (PMID 15690474, DOI 10.1002/hep.20537)

- (en) F. Holzinger, K. Z'graggen, M. Büchler, « Mechanisms of biliary carcinogenesis: a pathogenetic multi-stage cascade towards cholangiocarcinoma », Ann Oncol, vol. 10 Suppl 4, , p. 122–6. (PMID 10436802)

- (en) G. Gores, « Cholangiocarcinoma: current concepts and insights », Hepatology, vol. 37, no 5, , p. 961–9. (PMID 12717374, DOI 10.1053/jhep.2003.50200)

- "2017:Biofilm Producing Salmonella Typhi: Chronic Colonization and Development of Gallbladder Cancer"

- "2018:The Typhoid Toxin Produced by the Nontyphoidal Salmonella enterica Serotype Javiana Is Required for Induction of a DNA Damage Response In Vitro and Systemic Spread In Vivo"

- "2017:Biofilm Producing Salmonella Typhi: Chronic Colonization and Development of Gallbladder Cancer"

- (en) C. J. Scarlett, A. J. Saxby, A. Q. Nielsen, C. Bell, J. S. Samra, T. Hugh, R. C. Baxter, R. C. Smith, « Proteomic profiling of cholangiocarcinoma: Diagnostic potential of SELDI-TOF MS in malignant bile duct structure », Hepatology, vol. 44, no 3, , p. 658-66. (DOI 10.1002/hep.21294)

- Études sur la performance des marqueurs sériques (tels l'antigène carcino-embryonnaire ou CA 19.9) dans le dépistage du cholangiocarcinome :

- (en) D. Marrelli et al., « CA19-9 serum levels in obstructive jaundice: clinical value in benign and malignant conditions », Am J Surg, vol. 198, no 3, , p. 333-9. (DOI 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.12.031)

- (en) O. Nehls, M. Gregor, B. Klump, « Serum and bile markers for cholangiocarcinoma », Semin Liver Dis, vol. 24, no 2, , p. 139–54. (PMID 15192787, DOI 10.1055/s-2004-828891)

- (en) E. Siqueira, R. Schoen, W. Silverman, J. Martin, M. Rabinovitz, J. Weissfeld, K. Abu-Elmaagd, J. Madariaga, A. Slivka, J. Martini, « Detecting cholangiocarcinoma in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis », Gastrointest Endosc, vol. 56, no 1, , p. 40–7. (PMID 12085033, DOI 10.1067/mge.2002.125105)

- (en) C. Levy, J. Lymp, P. Angulo, G. Gores, N. Larusso, K. Lindor, « The value of serum CA 19-9 in predicting cholangiocarcinomas in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis », Dig Dis Sci, vol. 50, no 9, , p. 1734–40. (PMID 16133981, DOI 10.1007/s10620-005-2927-8)

- (en) A. Patel, D. Harnois, G. Klee, N. LaRusso, G. Gores, « The utility of CA 19-9 in the diagnoses of cholangiocarcinoma in patients without primary sclerosing cholangitis », Am J Gastroenterol, vol. 95, no 1, , p. 204–7. (PMID 10638584, DOI 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.01685.x)

- (en) S. Saini, « Imaging of the hepatobiliary tract », N Engl J Med, vol. 336, no 26, , p. 1889–94. (PMID 9197218, DOI 10.1056/NEJM199706263362607)

- (en) M. Sharma, V. Ahuja, « Aetiological spectrum of obstructive jaundice and diagnostic ability of ultrasonography: a clinician's perspective », Trop Gastroenterol, vol. 20, no 4, , p. 167–9. (PMID 10769604)

- (en) C. Bloom, B. Langer, S. Wilson, « Role of US in the detection, characterization, and staging of cholangiocarcinoma », Radiographics, vol. 19, no 5, , p. 1199–218. (PMID 10489176)

- "Youtube, echo-endoscopie"

- "2005,Place de l'écho-endoscopie dans les maladies de la vésicule biliaire"

- (en) C. Valls, A. Gumà, I. Puig, A. Sanchez, E. Andía, T. Serrano, J. Figueras, « Intrahepatic peripheral cholangiocarcinoma: CT evaluation », Abdom Imaging, vol. 25, no 5, , p. 490–6. (PMID 10931983, DOI 10.1007/s002610000079)

- (en) M. Tillich, H. Mischinger, K. Preisegger, H. Rabl, D. Szolar, « Multiphasic helical CT in diagnosis and staging of hilar cholangiocarcinoma », AJR Am J Roentgenol, vol. 171, no 3, , p. 651–8. (PMID 9725291)

- (en) Y. Zhang, M. Uchida, T. Abe, H. Nishimura, N. Hayabuchi, Y. Nakashima, « Intrahepatic peripheral cholangiocarcinoma: comparison of dynamic CT and dynamic MRI », J Comput Assist Tomogr, vol. 23, no 5, , p. 670–7. (PMID 10524843, DOI 10.1097/00004728-199909000-00004)

- (en) N. Akamatsu, Y. Sugawara et al., « Diagnostic accuracy of multidetector-row computed tomography for hilar cholangiocarcinoma », Hepatology, (DOI 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.06113.x)

- (en) M. Sugiyama, H. Hagi, Y. Atomi, M. Saito, « Diagnosis of portal venous invasion by pancreatobiliary carcinoma: value of endoscopic ultrasonography », Abdom Imaging, vol. 22, no 4, , p. 434–8. (PMID 9157867, DOI 10.1007/s002619900227)

- (en) L. Schwartz, F. Coakley, Y. Sun, L. Blumgart, Y. Fong, D. Panicek, « Neoplastic pancreaticobiliary duct obstruction: evaluation with breath-hold MR cholangiopancreatography », AJR Am J Roentgenol, vol. 170, no 6, , p. 1491–5. (PMID 9609160)

- (en) S. Zidi, F. Prat, O. Le Guen, Y. Rondeau, G. Pelletier, « Performance characteristics of magnetic resonance cholangiography in the staging of malignant hilar strictures », Gut, vol. 46, no 1, , p. 103–6. (PMID 10601064, DOI 10.1136/gut.46.1.103)

- (en) M. Lee, K. Park, Y. Shin, H. Yoon, K. Sung, M. Kim, S. Lee, E. Kang, « Preoperative evaluation of hilar cholangiocarcinoma with contrast-enhanced three-dimensional fast imaging with steady-state precession magnetic resonance angiography: comparison with intraarterial digital subtraction angiography », World J Surg, vol. 27, no 3, , p. 278–83. (PMID 12607051, DOI 10.1007/s00268-002-6701-1)

- (en) T. Yeh, Y. Jan, J. Tseng, C. Chiu, T. Chen, T. Hwang, M. Chen, « Malignant perihilar biliary obstruction: magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatographic findings », Am J Gastroenterol, vol. 95, no 2, , p. 432–40. (PMID 10685746, DOI 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.01763.x)

- (en) M. Freeman, T. Sielaff, « A modern approach to malignant hilar biliary obstruction », Rev Gastroenterol Disord, vol. 3, no 4, , p. 187–201. (PMID 14668691)

- (en) J. Szklaruk, E. Tamm, C. Charnsangavej, « Preoperative imaging of biliary tract cancers », Surg Oncol Clin N Am, vol. 11, no 4, , p. 865–76. (PMID 12607576, DOI 10.1016/S1055-3207(02)00032-7)

- Image d'une cholangiopancréatographie IRM d'un cholangiocarcinome

- (en) S. Weber, R. DeMatteo, Y. Fong, L. Blumgart, W. Jarnagin, « Staging laparoscopy in patients with extrahepatic biliary carcinoma. Analysis of 100 patients », Ann Surg, vol. 235, no 3, , p. 392–9. (PMID 11882761, DOI 10.1097/00000658-200203000-00011)

- (en) M. Callery, S. Strasberg, G. Doherty, N. Soper, J. Norton, « Staging laparoscopy with laparoscopic ultrasonography: optimizing resectability in hepatobiliary and pancreatic malignancy », J Am Coll Surg, vol. 185, no 1, , p. 33–9. (PMID 9208958)

- Ramacciato G et al., « Facteurs pronostiques après résection pour cholangiocarcinome hilaire », Annales de Chirurgie, vol. 131, nos 6-7, , p. 379-85. (DOI 10.1016/j.anchir.2006.03.006)

- (de) F. Länger, R. von Wasielewski, H. H. Kreipe, « Bedeutung der Immunhistochemie für die Diagnose des Cholangiokarzinoms », Pathologie, vol. 27, no 4, , p. 244–50. (PMID 16758167, DOI 10.1007/s00292-006-0836-z)

- (en) E. Patsenker, L. Wilkens, V. Banz, C.H. Österreicher, R. Weimann, S. Eisele, A. Keogh, D. Stroka, A. Zimmermann, F. Stickel, « The αvβ6 integrin is a highly specific immunohistochemical marker for cholangiocarcinoma », Journal of Hepatology, (DOI 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.12.006)

- (en) C. Su, S. Tsay, C. Wu, Y. Shyr, K. King, C. Lee, W. Lui, T. Liu, F. P'eng, « Factors influencing postoperative morbidity, mortality, and survival after resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma », Ann Surg, vol. 223, no 4, , p. 384–94. (PMID 8633917, DOI 10.1097/00000658-199604000-00007)

- Cas de l'opérabilité d'un cholangiocarcinome hilaire

- Voir Le traitement du cholangiocarcinome intrahépatique, section La chirurgie.

- (en) W. Kenneth Washburn, W. David Lewis, Roger L. Jenkins, « Aggressive Surgical Resection for Cholangiocarcinoma », Arch Surg, vol. 130, no 3, , p. 270-276 (ISSN 0004-0010, PMID 7534059)

- (en) M. Ohtsuka, H. Ito, F. Kimura, H. Shimizu, A. Togawa, H. Yoshidome, Dr M. Miyazaki, « Results of surgical treatment for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and clinicopathological factors influencing survival », British Journal of Surgery, vol. 89, no 12, , p. 1521-1535 (DOI 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02268.x)

- (en) Zhong Chen, Jianjun Yan, Liang Huang, Yiqun Yan, « Prognostic analysis of patients suffering from intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma », The Chinese-German Journal of Clinical Oncology, vol. 10, no 3, , p. 150-152 (DOI 10.1007/s10330-011-0738-2)

- (en) T. Todoroki, K. Ohara, T. Kawamoto, N. Koike, S. Yoshida, H. Kashiwagi, M. Otsuka, K. Fukao, « Benefits of adjuvant radiotherapy after radical resection of locally advanced main hepatic duct carcinoma », Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, vol. 46, no 3, , p. 581–7 (PMID 10701737)

- (en) M. Alden, M. Mohiuddin, « The impact of radiation dose in combined external beam and intraluminal Ir-192 brachytherapy for bile duct cancer », Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, vol. 28, no 4, , p. 945–51 (PMID 8138448)

- (en) D. González, D. Gouma, E. Rauws, T. van Gulik, A. Bosma, C. Koedooder, « Role of radiotherapy, in particular intraluminal brachytherapy, in the treatment of proximal bile duct carcinoma », Ann Oncol, vol. 10 Suppl 4, , p. 215–20 (PMID 10436826)

- (en) H. Pitt, A. Nakeeb, R. Abrams, J. Coleman, S. Piantadosi, C. Yeo, K. Lillemore, J. Cameron, « Perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. Postoperative radiotherapy does not improve survival », Ann Surg, vol. 221, no 6, , p. 788–97; discussion 797–8 (PMID 7794082, DOI 10.1097/00000658-199506000-00017)

- (en) T. Takada, H. Amano, H. Yasuda, Y. Nimura, T. Matsushiro, H. Kato, T. Nagakawa, T. Nakayama, « Is postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy useful for gallbladder carcinoma? A phase III multicenter prospective randomized controlled trial in patients with resected pancreaticobiliary carcinoma », Cancer, vol. 95, no 8, , p. 1685–95 (PMID 12365016, DOI 10.1002/cncr.10831)

- [PDF] Traitement chirurgical du cholangiocarcinome du hile

- [PDF] Traitement chirurgical du cholangiocarcinome périphérique

- (en) B. Glimelius, K. Hoffman, P. Sjödén, G. Jacobsson, H. Sellström, L. Enander, T. Linné, C. Svensson, « Chemotherapy improves survival and quality of life in advanced pancreatic and biliary cancer », Ann Oncol, vol. 7, no 6, , p. 593–600 (PMID 8879373)

- (en) C. Choi, I. Choi, J. Seo, B. Kim, J. Kim, C. Kim, S. Um, Y. Kim, « Effects of 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin in the treatment of pancreatic-biliary tract adenocarcinomas », Am J Clin Oncol, vol. 23, no 4, , p. 425–8 (PMID 10955877, DOI 10.1097/00000421-200008000-00023)

- (en) J. Park, S. Oh, S. Kim, H. Kwon, J. Kim, H. Jin-Kim, Y. Kim, « Single-agent gemcitabine in the treatment of advanced biliary tract cancers: a phase II study », Jpn J Clin Oncol, vol. 35, no 2, , p. 68–73 (PMID 15709089, DOI 10.1093/jjco/hyi021)

- (en) F. Giuliani, V. Gebbia, E. Maiello, N. Borsellino, E. Bajardi, G. Colucci, « Gemcitabine and cisplatin for inoperable and/or metastatic biliary tree carcinomas: a multicenter phase II study of the Gruppo Oncologico dell'Italia Meridionale (GOIM) », Ann Oncol, vol. 17 Suppl 7, , vii73-vii77 (PMID 16760299)

- (en) P. Bhargava, C. Jani, D. Savarese, J. O'Donnell, K. Stuart, C. Rocha Lima, « Gemcitabine and irinotecan in locally advanced or metastatic biliary cancer: preliminary report », Oncology (Williston Park), vol. 17, no 9 Suppl 8, , p. 23–6 (PMID 14569844)

- (en) J. Knox, D. Hedley, A. Oza, R. Feld, L. Siu, E. Chen, M. Nematollahi, G. Pond, J. Zhang, M. Moore, « Combining gemcitabine and capecitabine in patients with advanced biliary cancer: a phase II trial », J Clin Oncol, vol. 23, no 10, , p. 2332–8 (PMID 15800324, DOI 10.1200/JCO.2005.51.008)

- (en) P. Philip, M. Mahoney, C. Allmer, J. Thomas, H. Pitot, G. Kim, R. Donehower, T. Fitch, J. Picus, C. Erlichman, « Phase II study of erlotinib in patients with advanced biliary cancer », J Clin Oncol, vol. 24, no 19, , p. 3069–74 (PMID 16809731, DOI 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.3579)

- (en) Valle, Juan, Wasan, Harpreet, Palmer, H. Daniel, Cunningham, David, Anthoney, Alan, Maraveyas, Anthony, Madhusudan, Srinivasan, Iveson, Tim, Hughes, Sharon, Pereira, P. Stephen, Roughton, Michael, Bridgewater, John, the ABC-02 Trial Investigators, Cisplatin plus Gemcitabine versus Gemcitabine for Biliary Tract Cancer N Engl J Med 2010;362:1273-81.

- Dr Hubert Claes, « Un traitement par irinotécan liposomal en deuxième ligne améliore la survie en cas de cancer métastatique des voies biliaires », Belgian oncology & hematology news, (lire en ligne, consulté le )

- J. M. Regimbeau, D. Fuks, D. Chatelain, M. Riboulot, R. Delcenserie, T. Yzet, « Prise en charge chirurgicale du cholangiocarcinome hilaire résécable », Gastroentérologie clinique et biologique, vol. 32, nos 6-7, , p. 620-631 (ISSN 0399-8320)

- (en) M. Yamamoto, K. Takasaki, T. Yoshikawa, « Lymph Node Metastasis in Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma », Japanese Journal of Clinical Oncology, vol. 29, no 3, , p. 147–150 (PMID 10225697, DOI 10.1093/jjco/29.3.147)

- (en) D. Farley, A. Weaver, D. Nagorney, « « Natural history » of unresected cholangiocarcinoma: patient outcome after noncurative intervention », Mayo Clin Proc, vol. 70, no 5, , p. 425–9 (PMID 7537346, DOI 10.4065/70.5.425)

- (en) M. K. Grove, R. E. Hermann, D. P. Vogt, T. A. Broughan, « Role of radiation after operative palliation in cancer of the proximal bile ducts », Am J Surg, vol. 161, , p. 454–458 (DOI 10.1016/0002-9610(91)91111-U)

- Sulpice, L. (2014). Rôle du microenvironnement dans la progression du cholangiocarcinome intrahépatique: mécanismes moléculaires impliqués et recherche de biomarqueurs pronostiques (Doctoral dissertation, Rennes 1).

- (en) E. Zervos, D. Osborne, S. Goldin, D. Villadolid, D. Thometz, A. Durkin, L. Carey, A. Rosemurgy, « Stage does not predict survival after resection of hilar cholangiocarcinomas promoting an aggressive operative approach », Am J Surg, vol. 190, no 5, , p. 810–5 (PMID 16226963, DOI 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.07.025)

- (en) J. Tsao, Y. Nimura, J. Kamiya, N. Hayakawa, S. Kondo, M. Nagino, M. Miyachi, M. Kanai, K. Uesaka, K. Oda, R. Rossi, J. Braasch, J. Dugan, « Management of hilar cholangiocarcinoma: comparison of an American and a Japanese experience », Ann Surg, vol. 232, no 2, , p. 166–74 (PMID 10903592, DOI 10.1097/00000658-200008000-00003)

- (en) V. Rajagopalan, W. Daines, M. Grossbard, P. Kozuch, « Gallbladder and biliary tract carcinoma: A comprehensive update, Part 1 », Oncology (Williston Park), vol. 18, no 7, , p. 889–96 (PMID 15255172)

- Chirurgie radicale des cholangiocarcinomes périphériques

- Cholangiocarcinome périphérique, voir le tableau au paragraphe Résultats, par Yves-Patrice Le Treut.

Articles connexes

Bibliographie

- Patel T (2014) New insights into the molecular pathogenesis of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Journal of gastroenterology, 49(2), 165-172.