Conséquences de la Shoah

La Shoah a provoqué des évolutions profondes sur la société, tant en Europe que dans le reste du monde. Ses conséquences demeurent perceptibles par les enfants et les adultes dont les ancêtres sont des victimes de ce génocide[1].

Accès aux archives en Allemagne

Face à l'immensité des preuves et à l'horreur de la Shoah, une forte proportion de la société allemande a réagi en adoptant une attitude d'auto-justification et de profil bas. Dans les années qui suivent la guerre, des Allemands ont tenté de récrire leur propre histoire pour la rendre plus acceptable[2]. Pendant des décennies, l'Allemagne de l'Ouest, puis l'Allemagne réunifiée, a refusé l'accès à ses archives relatives à la Shoah rassemblées à Bad Arolsen en avançant des inquiétudes sur la vie privée. Après vingt années d'efforts par l'United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, en mai 2006 il est annoncé que 30 à 50 millions de pages deviendraient consultables pour les survivants, les historiens et d'autres personnes[3].

Survivants

Personnes déplacées et État d'Israël

La Shoah laisse des millions de réfugiés, dont de nombreux Juifs qui ont perdu la totalité ou la plupart de leurs proches et de leurs possessions et qui souvent subissent un antisémitisme persistant dans leurs pays d'origine. À l'origine, les Alliés prévoient de rapatrier ces « personnes déplacées » dans leurs patries d'origine mais beaucoup de personnes refusent de rentrer ou ne peuvent plus le faire, car leurs habitations et leurs communautés sont détruites. Par conséquent, plus de 250 000 personnes dépérissent dans les camps de personnes déplacées pendant des années après la fin de la guerre. De nombreux camps tenus par les États-Unis présentaient des conditions de vie effroyables ; les réfugiés y vivaient sous une garde armée permanente, comme l'a révélé le rapport Harrison[4] - [5] - [6].

Comme la plupart des personnes déplacées ne peuvent ou ne veulent pas rentrer dans leurs patries en Europe, et compte tenu des restrictions pesant encore sur l'immigration dans de nombreux pays occidentaux, la Palestine mandataire est devenue la principale destination des nombreux réfugiés juifs. Toutefois, face à l'opposition des arabes locaux, le Royaume-Uni interdit l'entrée des réfugiés juifs sur le territoire de Palestine. Les pays du bloc de l'Est instaurent des obstacles à l'émigration. D'anciens résistants juifs en Europe, en coopération avec la Haganah, organise des efforts massifs pour faire entrer illégalement des Juifs en Palestine : ces opérations, appelées Berih'ah, permettent de transporter 250 000 Juifs (tant les personnes déplacées que celles qui étaient cachées pendant la guerre) vers la Palestine mandataire. En 1948, après la déclaration d'indépendance de l'État d'Israël, les Juifs peuvent migrer légalement et sans restriction en Israël. En 1952, année de la fermeture des camps de personnes déplacées, plus de 80 000 personnes juives ayant vécu dans ces camps se sont installées aux États-Unis ; environ 136 000 en Israël et 1 000 autres dans des pays tiers, y compris le Mexique, le Japon, et des États d'Afrique et d'Amérique latine[7].

Résurgences d'antisémitisme

Les rares Juifs survivants en Pologne voient leurs effectifs augmenter avec le retour des émigrés depuis l'Union soviétique et des rescapés des camps de concentration en Allemagne. Toutefois, des résurgences d'antisémitisme en Pologne, comme le Pogrom de Cracovie le et celui de Kielce le provoquent l'exode d'une part importante de la communauté juive, qui ne se sent plus en sécurité dans le pays[8]. Des émeutes antisémites éclatent dans d'autres villes polonaises causent de nombreux morts parmi les Juifs[9].

Ces atrocités se nourrissent en partie d'une croyance répandue dans la population polonaise, celle du Żydokomuna (judéo-communisme, déclinaison locale du judéo-bolchevisme) qui rejette les Juifs au prétexte qu'ils soutiennent le communisme. L'accusation de Żydokomuna fait partie des causes qui sous-tendent une intensification d'antisémitisme en Pologne dans les années 1945-1948, dont certains estiment qu'il était encore pire que dans les années 1939 ; des centaines de Juifs sont assassinés lors de violences antisémites. Certains sont tués simplement parce qu'ils tentent de recouvrer leurs biens[10]. En conséquence de cet exode, le nombre de Juifs, qui dans les années d'après-guerre s'élève à 200 000 personnes s'est réduit à 50 000 en 1950 et 6 000 dans les années 1980[11].

Des pogroms de moindre envergure ont aussi éclaté après-guerre en Hongrie[10].

Sort des survivants en Israël

En mai 2016, Haaretz rapporte que 45 000 survivants de la Shoah vivent sous le seuil de pauvreté en Israël et qu'ils ont besoin d'une assistance plus solide. De telles situations conduisent à des manifestations vigoureuses et spectaculaires de la part de certains survivants contre le gouvernement israélien (en) et des organismes qui en dépendent. Le taux moyen de cancer chez les survivants est près de deux fois et demie plus élevé que la moyenne nationale ; la fréquence du cancer du colon, imputé aux expériences de famine et de stress extrême chez les victimes, est neuf fois plus élevée. En 2016, la communauté des survivants établis en Israël ne représentait plus que 189 000 personnes[12] - [13] - [14].

Recherche d'archives sur les victimes

Il y a un regain d'intérêt chez les descendants des survivants pour enquêter sur le sort de leur famille. Yad Vashem propose une base de données consultables comportant trois millions de noms, dont la moitié sont des victimes juives recensées. Cette base de données est accessible en ligne ou en personne. Il existe d'autres bases de données et listes recensant les noms des victimes.

Effets sur la culture

Répercussions sur la langue et la culture yiddish

Dans les décennies qui précèdent la Seconde Guerre mondiale, il existait un immense mouvement de reconnaissance du yiddish en tant que langue européenne juive officielle et on assistait même à une « renaissance yiddish (en) », surtout en Pologne. À la veille de la guerre, le yiddish comptait entre onze et treize millions de locuteurs dans le monde[15]. La Shoah a détruit le berceau Est-européen du yiddish, même si la langue connaissait une érosion. Dans les années 1920 et 1930, le grand public soviétique juif rejette l'autonomie culturelle que lui offre le gouvernement et préfère la russification[16] : si 70,4 % des Juifs soviétiques déclarent en 1926 que leur langue maternelle est le yiddish, ils ne sont plus que 39,7 % en 1939. Même en Pologne, où des discriminations féroces faisaient des Juifs un groupe ethnique d'une grande cohésion, le yiddish connaissait un déclin rapide en faveur de la polonisation. En 1931, 80 % de la population juive totale se déclare de langue maternelle yiddish, mais ce taux chute chez les lycéens et atteint 53 % en 1937[17]. Aux États-Unis, la préservation de la langue ne constituait qu'un phénomène unigénérationnel : les enfants des immigrants abandonnaient vite la langue de leurs parents au profil de l'anglais[18].

À partir de l'invasion de la Pologne par les nazis en 1939, et tout au long de la guerre avec la destruction continue de la culture yiddish en Europe, cette langue et cette culture sont pratiquement éradiqués d'Europe. La Shoah a provoqué un déclin catastrophique du yiddish : en effet, les vastes communautés juives, tant séculaires que religieuses, qui utilisaient le yiddish au quotidien sont victimes d'extermination. Près de cinq millions de victimes de la Shoah, soit 85 % du total, étaient locutrices du yiddish[19].

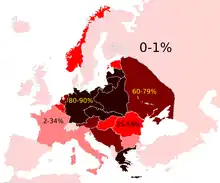

Théologie après la Shoah

La théologie après la Shoah est la somme des débats théologiques et philosophiques sur le rôle de Dieu dans les religions abrahamiques (en) dans l'univers à la lumière de la Shoah perpétrée entre la fin des années 1938 et le milieu des années 1940. Cette question est principalement examinée par le judaïsme car les Juifs ont subi de plein fouet la Shoah, qui a entraîné le génocide de six millions d'entre eux aux mains du Troisième Reich et de ses alliés[note 1] - [21]. L'assassinat des Juifs représente une portion plus élevée que d'autres groupes cibles ; certains experts circonscrivent la portée de la Shoah en la réservant aux seules victimes juives des nazis, seules concernées par la « solution finale ». D'autres experts élargissent sa portée aux cinq millions de victimes non juives, portant le total à 11 millions[22]. La Shoah a provoqué la mort d'un tiers de la population juive mondiale ; les communautés juives d'Europe de l'Est sont les plus touchées, car elles ont perdu 90 % de leurs membres.

Les Juifs orthodoxes estiment que la survenue de la Shoah ne diminue pas leur foi en Dieu. Selon cet avis, une créature ne pourra jamais entièrement comprendre son créateur, de la même manière qu'un enfant dans un bloc chirurgical ne peut comprendre pourquoi des gens découpent le corps d'une personne en vie. Comme le Rebbe Loubavitch l'a déclaré à Elie Wiesel, après avoir été témoin de la Shoah et après avoir compris à quelles bassesses les humains peuvent se réduire, à qui peut-on faire confiance, sinon à Dieu[23] ?

Art et littérature

Theodor Adorno écrit : « écrire des vers après Auschwitz est une barbarie »[24] et que la Shoah produit un effet profond sur les arts et la littérature, tant pour les Juifs que pour les non-Juifs. Certaines des œuvres les plus célèbres sur le sujet émanent de survivants et de victimes de la Shoah, comme Elie Wiesel, Primo Levi, Viktor Frankl aet Anne Frank, mais il existe de nombreuses œuvres dans une grande diversité de langues. D'ailleurs, Paul Celan a composé le poème Todesfuge[25] en réponse à l'avis d'Adorno.

La Shoah est le thème de nombreux films, dont certains ont remporté des récompenses, comme La Liste de Schindler, Le Pianiste et La vie est belle. Compte tenu du vieillissement de la population des survivants de la Shoah, ces dernières années ont vu une attention croissante pour préserver la mémoire de la Shoah en recueillant les récits des rescapés, notamment dans les institutions vouées à la mémoire et à l'étude de la Shoah, comme Yad Vashem en Israël et l'United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Propriété d'œuvres d'art européennes avant 1945

La Shoah a produit des conséquences désastreuses sur les œuvres qui existaient à l'époque. De 1933 à 1945, les nazis ont pillé quelque 600 000 œuvres pour un montant équivalent à 2,5 milliards de dollars (soit 20,5 milliards selon la valeur de 2003) présentes dans des musées et des collections privées issues de toute l'Europe[26]. Les œuvres d'art appartenant à des Juifs étaient ciblées en priorité dans la politique de confiscation[27]. Comme l'a exprimé l'héritier d'un survivant de la Shoah : « Vous m'avez demandé : ont-ils tué ? Oui. Ils tuaient pour acquérir des œuvres, si elles leur plaisaient. Donc tuer des Juifs et confisquer des œuvres allait de pair »"[26]. Il en découle que les œuvres dont l'existence précède l'année 1945 peuvent poser des problèmes de provenance[28].

Cette question pose de graves obstacles quand un acquéreur souhaite obtenir des œuvres d'art européennes créées avant 1945. Pour conjurer le risque de gaspiller des centaines voire des millions de dollars, ces acquéreurs doivent s'assurer (le plus souvent, avec l'aide un historien de l'art et d'un juriste spécialisé dans le droit artistique) que les œuvres convoitées ne proviennent pas du pillage des nazis à l'encontre des victimes de la Shoah. Ce problème difficile a donné lieu à des procès très médiatisés, comme Republic of Austria v. Altmann (2006) et Germany v. Philipp (en) (2021).

Réparations

Dans l'immédiat après-guerre, l'agence juive dirigée par Chaim Weizmann adresse aux Alliés un mémorandum pour exiger des réparations de l'Allemagne en faveur des Juifs mais sa réclamation ne reçoit aucune réponse. En mars 1951, Moshe Sharett (ministre israélien des affaires étrangères) dépose une nouvelle demande en réclamant 1,5 milliard de dollars en faveur d'Israël à titre de compensation pour les frais engagés par l'État pour les soins nécessaires à 500 000 survivants juifs. Konrad Adenauer, chancelier d'Allemagne de l'Ouest, accepte ces conditions et se déclare disposé à négocier d'autres réparations. Nahum Goldmann fonde à New York une conférence sur les demandes à l'Allemagne afin d'aider les requérants individuels. Après des négociations, le montant des compensations est revnu à baisse et correspond à 845 millions de dollars en compensations directes et indirectes, à verser sur une période de quatorze ans. En 1988, l'Allemagne de l'Ouest verse encore 152 millions de dollars à titre de réarations[29].

En 1999, de nombreuses sociétés allemandes comme Deutsche Bank, Siemens et BMW font l'objet de poursuites en raison de leur rôle dans le travail forcé instauré pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale. Pour mettre fin à ces poursuites, l'Allemagne accepte de constituer un fonds de 5 milliards de dollars ; les anciennes victimes juives de travaux forcés encore vivantes peuvent y déposer une requête pour recevoir un versement compris entre 2 500 $ et 7 500 $[29]. En 2012, l'Allemagne accepte de payer une nouvelle réparation de 772 millions d'euros à l'issue de négociations avec Israël[30].

En 2014, la SNCF (société nationale des chemins de fer français) est contrainte de remettre 60 millions de dollars aux survivants juifs américains de la Shoah en raison de son rôle dans le transport de personnes déportées vers l'Allemagne. Ce montant représente environ 100 000 $ par survivant[31]. Ce jugement est prononcé même si la SNCF ait été contrainte de coopérer par les autorités allemandes, en mettant à leur disposition du matériel de transport pour les Juifs français jusqu'à la frontière, et bien qu'elle n'ait tiré aucun bénéfice de ces déportations, d'après Serge Klarsfeld, président de l'association des Fils et filles de déportés juifs de France[32].

Journées en mémoire de la Shoah

.jpg.webp)

Le , l'Assemblée générale des Nations unies adopte une résolution désignant le 27 janvier comme journée internationale dédiée à la mémoire des victimes de l'Holocauste (International Day of Commemoration in Memory of the Victims of the Holocaust). C'est le qu'a lieu la libération du camp de concentration et d'extermination d'Auschwitz. Cette journée était déjà observée en tant que journée en mémoire de la Shoah dans plusieurs pays. L'État d'Israël et la diaspora juive observent Yom HaShoah le 27 du mois de Nissan, qui tombe généralement en avril[33].

Négation de la Shoah

La négation de la Shoah consiste à prétendre que le génocide entrepris contre les Juifs pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale — désigné sous les noms de Shoah ou Holocauste —[1] ne s'est pas produit selon les procédés et avec la portée que les experts actuels décrivent.

Les principaux éléments invoqués dans ces thèses reposent sur le rejet des déclarations suivantes : le gouvernement nazi a appliqué une politique intentionnelle ciblant les Juifs et les personnes de descendance juive pour les exterminer en tant que peuple ; entre cinq et sept millions de Juifs[1] ont été victimes de meurtres systématiques aux mains des nazis et de leurs alliés ; ce génocide a été exécutés dans des centres d'extermination au moyen d'instruments d'assassinat de masse, comme les chambres à gaz[note 2] - [note 3].

De nombreux partisans du négationnisme rejettent le terme « négationnisme » décrivant leur position et y substituent l'expression « révisionnisme de la Shoah »[note 4]. Certains experts, toutefois, préfèrent l'expression « négationnisme » pour opérer une distinction entre négationnistes et révisionnistes, car ces derniers recourent à des méthodes valables dans les études d'histoire[note 5].

La plupart des discours négationnistes laissent entendre, ou déclarent explicitement, que la Shoah est un canular né d'un complot juif intentionnel (en) pour favoriser les Juifs aux dépens d'autres peuples[note 6]. Pour cette raison, la négation de la Shoah est typiquement considérée comme une théorie du complot à caractère antisémite[note 7] - [note 8]. Les méthodes des négationnistes de la Shoah font l'objet de critiques car elles se fondent sur une conclusion prévue par avance sans tenir compte des abondantes preuves historiques qui invalident leur thèse[note 9].

Sensibilisation au thème de la Shoah

Alan Posener (en), journaliste germano-britannique, déclare « ... l'incapacité des films et séries télévisées allemandes de traiter, de manière responsable, le passé du pays et d'attirer les jeunes spectateurs favorise une amnésie croissante chez les jeunes Allemands regardant leur propre histoire... Une étude de 2017 menée par la fondation Körber (en) montre que 40 % des jeunes de 14 ans interrogés ne savent pas ce qu'est Auschwitz »[34].

D'après une enquête publiée en avril 2018, pendant la Journée internationale dédiée à la mémoire des victimes de l'Holocauste, 41 % des 1 350 adultes interrogés et 66 % de la génération Y ne savent pas ce qu'est Auschwitz. Dans cette deuxième tranche d'âge, 41 % déclarent — à tort — que 2 millions de Juifs, voire moins, ont péri pendant la Shoah tandis que 22 % déclarent n'avoir jamais entendu parler de la Shoah. Plus de 95 % de l'ensemble des Américains interrogés ne savent pas que la Shoah a frappé les pays baltes de Lettonie, Lituanie et Estonie. 45 % des adultes de 49 % de la génération Y ne peuvent nommer aucun camp de concentration nazi ou ghetto en Europe occupée pendant la Shoah[35]. En comparaison, une enquête menée en Israël a montré que les jeunes générations s'adonnant aux réseaux sociaux se servent de la Shoah comme argument hors de propos quand elles veulent critiquer et s'opposer à la politique sécuritaire en Israël[36].

Notes et références

- (en) Cet article est partiellement ou en totalité issu de l’article de Wikipédia en anglais intitulé « Aftermath of the Holocaust » (voir la liste des auteurs).

Notes

- Snyder 2010, p. 45. Further examples of this usage can be found in: Bauer 2002, ,[20] - Longerich 2012{

- Key elements of Holocaust denial:

- "Before discussing how Holocaust denial constitutes a conspiracy theory, and how the theory is distinctly American, it is important to understand what is meant by the term "Holocaust denial." Holocaust deniers, or "revisionists," as they call themselves, question all three major points of definition of the Nazi Holocaust. First, they contend that, while mass murders of Jews did occur (although they dispute both the intentionality of such murders as well as the supposed deservedness of these killings), there was no official Nazi policy to murder Jews. Second, and perhaps most prominently, they contend that there were no homicidal gas chambers, particularly at Auschwitz-Birkenau, where mainstream historians believe over 1 million Jews were murdered, primarily in gas chambers. And third, Holocaust deniers contend that the death toll of European Jews during World War II was well below 6 million. Deniers float numbers anywhere between 300,000 and 1.5 million, as a general rule." Mathis, Andrew E. Holocaust Denial, a Definition « https://web.archive.org/web/20110609180542/http://www.holocaust-history.org/denial/abc-clio/ »(Archive.org • Wikiwix • Archive.is • Google • Que faire ?), , The Holocaust History Project, July 2, 2004. Retrieved December 18, 2006.

- "In part III we directly address the three major foundations upon which Holocaust denial rests, including... the claim that gas chambers and crematoria were used not for mass extermination but rather for delousing clothing and disposing of people who died of disease and overwork; ... the claim that the six million figure is an exaggeration by an order of magnitude—that about six hundred thousand, not six million, died at the hands of the Nazis; ... the claim that there was no intention on the part of the Nazis to exterminate European Jewry and that the Holocaust was nothing more than the unfortunate by-product of the vicissitudes of war." Michael Shermer and Alex Grobman. Denying History: : who Says the Holocaust Never Happened and why Do They Say It?, University of California Press, 2000, (ISBN 0-520-23469-3), p. 3.

- "Holocaust Denial: Lies that the mass extermination of the Jews by the Nazis never happened; that the number of Jewish losses has been 'greatly exaggerated'; that the Holocaust was not systematic nor a result of an official policy; or simply that the Holocaust never took place." What is Holocaust Denial, Yad Vashem website, 2004. Retrieved December 18, 2006.

- "Among the untruths routinely promoted are the claims that no gas chambers existed at Auschwitz, that only 600,000 Jews were killed rather than twelve million, and that Hitler had no murderous intentions toward Jews or other groups persecuted by his government." Holocaust Denial « https://web.archive.org/web/20070404130634/http://www.adl.org/hate-patrol/holocaust.asp »(Archive.org • Wikiwix • Archive.is • Google • Que faire ?), , Anti-Defamation League, 2001. Retrieved June 28, 2007.

- "The kinds of assertions made in Holocaust-denial material include the following:

- Several hundred thousand rather than approximately twelve million Jews died during the war.

- Scientific evidence proves that gas chambers could not have been used to kill large numbers of people.

- The Nazi command had a policy of deporting Jews, not exterminating them.

- Some deliberate killings of Jews did occur, but were carried out by the peoples of Eastern Europe rather than the Nazis.

- Jews died in camps of various kinds, but did so as the result of hunger and disease. The Holocaust is a myth created by the Allies for propaganda purposes, and subsequently nurtured by the Jews for their own ends.

- Errors and inconsistencies in survivors’ testimonies point to their essential unreliability.

- Alleged documentary evidence of the Holocaust, from photographs of concentration camp victims to Anne Frank's diary, is fabricated.

- The confessions of former Nazis to war crimes were extracted through torture." The nature of Holocaust denial: What is Holocaust denial? « https://web.archive.org/web/20110718044959/http://www.jpr.org.uk/Reports/CS_Reports/no_3_2000/index.htm »(Archive.org • Wikiwix • Archive.is • Google • Que faire ?), , JPR report #3, 2000. Retrieved December 18, 2006.

- Refer to themselves as revisionists:

- "Holocaust deniers often refer to themselves as ‘revisionists’, in an attempt to claim legitimacy for their activities." (The nature of Holocaust denial: What is Holocaust denial? « https://web.archive.org/web/20110718044959/http://www.jpr.org.uk/Reports/CS_Reports/no_3_2000/index.htm »(Archive.org • Wikiwix • Archive.is • Google • Que faire ?), , JPR report #3, 2000. Retrieved May 16, 2007)

- "The deniers' selection of the name revisionist to describe themselves is indicative of their basic strategy of deceit and distortion and of their attempt to portray themselves as legitimate historians engaged in the traditional practice of illuminating the past." Deborah Lipstadt. Denying the Holocaust—The Growing Assault on Truth and Memory, Penguin, 1993, (ISBN 0-452-27274-2), p. 25.

- "Dressing themselves in pseudo-academic garb, they have adopted the term "revisionism" in order to mask and legitimate their enterprise." Introduction: Denial as Anti-Semitism « https://web.archive.org/web/20110604020743/http://www.adl.org/holocaust/theory.asp »(Archive.org • Wikiwix • Archive.is • Google • Que faire ?), , "Holocaust Denial: An Online Guide to Exposing and Combating Anti-Semitic Propaganda", Anti-Defamation League, 2001. Retrieved June 12, 2007.

- "Holocaust deniers often refer to themselves as ‘revisionists’, in an attempt to claim legitimacy for their activities." The nature of Holocaust denial: What is Holocaust denial? , JPR report #3, 2000. Retrieved May 16, 2007.

- Denial vs. "revisionism":

- "This is the phenomenon of what has come to be known as 'revisionism', 'negationism', or 'Holocaust denial,' whose main characteristic is either an outright rejection of the very veracity of the Nazi genocide of the Jews, or at least a concerted attempt to minimize both its scale and importance... It is just as crucial, however, to distinguish between the wholly objectionable politics of denial and the fully legitimate scholarly revision of previously accepted conventional interpretations of any historical event, including the Holocaust." Bartov, Omer. The Holocaust: Origins, Implementation and Aftermath, Routledge, pp.11-12. Bartov is John P. Birkelund Distinguished Professor of European History at the Watson Institute, and is regarded as one of the world's leading authorities on genocide ("Omer Bartov" « https://web.archive.org/web/20081216115629/http://www.watsoninstitute.org/contacts_detail.cfm?id=97 »(Archive.org • Wikiwix • Archive.is • Google • Que faire ?), , The Watson Institute for International Studies).

- "The two leading critical exposés of Holocaust denial in the United States were written by historians Deborah Lipstadt (1993) and Michael Shermer and Alex Grobman (2000). These scholars make a distinction between historical revisionism and denial. Revisionism, in their view, entails a refinement of existing knowledge about an historical event, not a denial of the event itself, that comes through the examination of new empirical evidence or a reexamination or reinterpretation of existing evidence. Legitimate historical revisionism acknowledges a "certain body of irrefutable evidence" or a "convergence of evidence" that suggest that an event_like the black plague, American slavery, or the Holocaust—did in fact occur (Lipstadt 1993:21; Shermer & Grobman 200:34). Denial, on the other hand, rejects the entire foundation of historical evidence..." Ronald J. Berger. Fathoming the Holocaust: A Social Problems Approach, Aldine Transaction, 2002, (ISBN 0-202-30670-4), p. 154.

- "At this time, in the mid-1970s, the specter of Holocaust Denial (masked as "revisionism") had begun to raise its head in Australia..." Bartrop, Paul R. "A Little More Understanding: The Experience of a Holocaust Educator in Australia" in Samuel Totten, Steven Leonard Jacobs, Paul R Bartrop. Teaching about the Holocaust, Praeger/Greenwood, 2004, p. xix. (ISBN 0-275-98232-7)

- "Pierre Vidal-Naquet urges that denial of the Holocaust should not be called 'revisionism' because 'to deny history is not to revise it'. Les Assassins de la Memoire. Un Eichmann de papier et autres essays sur le revisionisme (The Assassins of Memory—A Paper-Eichmann and Other Essays on Revisionism) 15 (1987)." Cited in Roth, Stephen J. "Denial of the Holocaust as an Issue of Law" in the Israel Yearbook on Human Rights, Volume 23, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1993, (ISBN 0-7923-2581-8), p. 215.

- "This essay describes, from a methodological perspective, some of the inherent flaws in the "revisionist" approach to the history of the Holocaust. It is not intended as a polemic, nor does it attempt to ascribe motives. Rather, it seeks to explain the fundamental error in the "revisionist" approach, as well as why that approach of necessity leaves no other choice. It concludes that "revisionism" is a misnomer because the facts do not accord with the position it puts forward and, more importantly, its methodology reverses the appropriate approach to historical investigation... "Revisionism" is obliged to deviate from the standard methodology of historical pursuit, because it seeks to mold facts to fit a preconceived result; it denies events that have been objectively and empirically proved to have occurred; and because it works backward from the conclusion to the facts, thus necessitating the distortion and manipulation of those facts where they differ from the preordained conclusion (which they almost always do). In short, "revisionism" denies something that demonstrably happened, through methodological dishonesty." McFee, Gordon. "Why 'Revisionism' Isn't" « https://web.archive.org/web/20100428044832/http://www.holocaust-history.org/revisionism-isnt/ »(Archive.org • Wikiwix • Archive.is • Google • Que faire ?), , The Holocaust History Project, May 15, 1999. Retrieved December 22, 2006.

- "Crucial to understanding and combating Holocaust denial is a clear distinction between denial and revisionism. One of the more insidious and dangerous aspects of contemporary Holocaust denial, a la Arthur Butz, Bradley Smith and Greg Raven, is the fact that they attempt to present their work as reputable scholarship under the guise of 'historical revisionism.' The term 'revisionist' permeates their publications as descriptive of their motives, orientation and methodology. In fact, Holocaust denial is in no sense 'revisionism,' it is denial... Contemporary Holocaust deniers are not revisionists — not even neo-revisionists. They are Deniers. Their motivations stem from their neo-nazi political goals and their rampant antisemitism." Austin, Ben S. "Deniers in Revisionists Clothing" « https://web.archive.org/web/20081121021941/http://www.mtsu.edu/~baustin/revision.htm »(Archive.org • Wikiwix • Archive.is • Google • Que faire ?), , The Holocaust\Shoah Page, Middle Tennessee State University. Retrieved March 29, 2007.

- "Holocaust denial can be a particularly insidious form of antisemitism precisely because it often tries to disguise itself as something quite different: as genuine scholarly debate (in the pages, for example, of the innocuous-sounding Journal for Historical Review). Holocaust deniers often refer to themselves as ‘revisionists’, in an attempt to claim legitimacy for their activities. There are, of course, a great many scholars engaged in historical debates about the Holocaust whose work should not be confused with the output of the Holocaust deniers. Debate continues about such subjects as, for example, the extent and nature of ordinary Germans’ involvement in and knowledge of the policy of genocide, and the timing of orders given for the extermination of the Jews. However, the valid endeavour of historical revisionism, which involves the re-interpretation of historical knowledge in the light of newly emerging evidence, is a very different task from that of claiming that the essential facts of the Holocaust, and the evidence for those facts, are fabrications." The nature of Holocaust denial: What is Holocaust denial? « https://web.archive.org/web/20110718044959/http://www.jpr.org.uk/Reports/CS_Reports/no_3_2000/index.htm »(Archive.org • Wikiwix • Archive.is • Google • Que faire ?), , JPR report #3, 2000. Retrieved May 16, 2007.

- "The deniers' selection of the name revisionist to describe themselves is indicative of their basic strategy of deceit and distortion and of their attempt to portray themselves as legitimate historians engaged in the traditional practice of illuminating the past. For historians, in fact, the name revisionism has a resonance that is perfectly legitimate -- it recalls the controversial historical school known as World War I "revisionists," who argued that the Germans were unjustly held responsible for the war and that consequently the Versailles treaty was a politically misguided document based on a false premise. Thus the deniers link themselves to a specific historiographic tradition of reevaluating the past. Claiming the mantle of the World War I revisionists and denying they have any objective other than the dissemination of the truth constitute a tactical attempt to acquire an intellectual credibility that would otherwise elude them." Deborah Lipstadt. Denying the Holocaust -- The Growing Assault on Truth and Memory, Penguin, 1993, (ISBN 0-452-27274-2), p. 25.

- A hoax designed to advance the interests of Jews:

- "The title of App's major work on the Holocaust, The Six Million Swindle, is informative because it implies on its very own the existence of a conspiracy of Jews to perpetrate a hoax against non-Jews for monetary gain." Mathis, Andrew E. Holocaust Denial, a Definition « https://web.archive.org/web/20110609180542/http://www.holocaust-history.org/denial/abc-clio/ »(Archive.org • Wikiwix • Archive.is • Google • Que faire ?), , The Holocaust History Project, July 2, 2004. Retrieved May 16, 2007.

- "Jews are thus depicted as manipulative and powerful conspirators who have fabricated myths of their own suffering for their own ends. According to the Holocaust deniers, by forging evidence and mounting a massive propaganda effort, the Jews have established their lies as ‘truth’ and reaped enormous rewards from doing so: for example, in making financial claims on Germany and acquiring international support for Israel." The nature of Holocaust denial: What is Holocaust denial? « https://web.archive.org/web/20110718044959/http://www.jpr.org.uk/Reports/CS_Reports/no_3_2000/index.htm »(Archive.org • Wikiwix • Archive.is • Google • Que faire ?), , JPR report #3, 2000. Retrieved May 16, 2007.

- "Why, we might ask the deniers, if the Holocaust did not happen would any group concoct such a horrific story? Because, some deniers claim, there was a conspiracy by Zionists to exaggerate the plight of Jews during the war in order to finance the state of Israel through war reparations." Michael Shermer & Alex Grobman. Denying History: : who Says the Holocaust Never Happened and why Do They Say It?, University of California Press, 2000, (ISBN 0-520-23469-3), p. 106.

- "Since its inception in 1979, the Institute for Historical Review (IHR), a California-based Holocaust denial organization founded by Willis Carto of Liberty Lobby, has promoted the antisemitic conspiracy theory that Jews fabricated tales of their own genocide to manipulate the sympathies of the non-Jewish world." Antisemitism and Racism Country Reports: United States « https://web.archive.org/web/20110628184616/http://www.tau.ac.il/Anti-Semitism/asw2000-1/usa.htm »(Archive.org • Wikiwix • Archive.is • Google • Que faire ?), , Stephen Roth Institute, 2000. Retrieved May 17, 2007.

- "The central assertion for the deniers is that Jews are not victims but victimizers. They 'stole' billions in reparations, destroyed Germany's good name by spreading the 'myth' of the Holocaust, and won international sympathy because of what they claimed had been done to them. In the paramount miscarriage of injustice, they used the world's sympathy to 'displace' another people so that the state of Israel could be established. This contention relating to the establishment of Israel is a linchpin of their argument." Deborah Lipstadt. Denying the Holocaust -- The Growing Assault onTruth and Memory, Penguin, 1993, (ISBN 0-452-27274-2), p. 27.

- "They [Holocaust deniers] picture a vast shadowy conspiracy that controls and manipulates the institutions of education, culture, the media and government in order to disseminate a pernicious mythology. The purpose of this Holocaust mythology, they assert, is the inculcation of a sense of guilt in the white, Western Christian world. Those who can make others feel guilty have power over them and can make them do their bidding. This power is used to advance an international Jewish agenda centered in the Zionist enterprise of the State of Israel." Introduction: Denial as Anti-Semitism « https://web.archive.org/web/20110604020743/http://www.adl.org/holocaust/theory.asp »(Archive.org • Wikiwix • Archive.is • Google • Que faire ?), , "Holocaust Denial: An Online Guide to Exposing and Combating Anti-Semitic Propaganda", Anti-Defamation League, 2001. Retrieved June 12, 2007.

- "Deniers argue that the manufactured guilt and shame over a mythological Holocaust led to Western, specifically United States, support for the establishment and sustenance of the Israeli state — a sustenance that costs the American taxpayer over three billion dollars per year. They assert that American taxpayers have been and continue to be swindled..." Introduction: Denial as Anti-Semitism, "Holocaust Denial: An Online Guide to Exposing and Combating Anti-Semitic Propaganda", Anti-Defamation League, 2001. Retrieved June 12, 2007.

- "The stress on Holocaust revisionism underscored the new anti-Semitic agenda gaining ground within the Klan movement. Holocaust denial refurbished conspiratorial anti-Semitism. Who else but the Jews had the media power to hoodwink unsuspecting masses with one of the greatest hoaxes in history? And for what motive? To promote the claims of the illegitimate state of Israel by making non-Jews feel guilty, of course." Lawrence N. Powell, Troubled Memory: Anne Levy, the Holocaust, and David Duke's Louisiana, University of North Carolina Press, 2000, (ISBN 0-8078-5374-7), p. 445.

- Antisemitic:

- "Denying the fact, scope, mechanisms (e.g. gas chambers) or intentionality of the genocide of the Jewish people at the hands of National Socialist Germany and its supporters and accomplices during World War II (the Holocaust)." EUMC Working Definition of Antisemitism« AS Working Definition Draft » [archive du ] (consulté le ). EUMC. Contemporary examples of antisemitism

- "It would elevate their antisemitic ideology — which is what Holocaust denial is — to the level of responsible historiography — which it is not." Deborah Lipstadt, Denying the Holocaust, (ISBN 0-14-024157-4), p. 11.

- "The denial of the Holocaust is among the most insidious forms of anti-Semitism..." Roth, Stephen J. "Denial of the Holocaust as an Issue of Law" in the Israel Yearbook on Human Rights, Volume 23, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1993, (ISBN 0-7923-2581-8), p. 215.

- "Contemporary Holocaust deniers are not revisionists — not even neo-revisionists. They are Deniers. Their motivations stem from their neo-nazi political goals and their rampant antisemitism." Austin, Ben S. "Deniers in Revisionists Clothing" « https://web.archive.org/web/20081121021941/http://www.mtsu.edu/~baustin/revision.htm »(Archive.org • Wikiwix • Archive.is • Google • Que faire ?), , The Holocaust\Shoah Page, Middle Tennessee State University. Retrieved March 29, 2007.

- "Holocaust denial can be a particularly insidious form of antisemitism precisely because it often tries to disguise itself as something quite different: as genuine scholarly debate (in the pages, for example, of the innocuous-sounding Journal for Historical Review)." The nature of Holocaust denial: What is Holocaust denial? « https://web.archive.org/web/20110718044959/http://www.jpr.org.uk/Reports/CS_Reports/no_3_2000/index.htm »(Archive.org • Wikiwix • Archive.is • Google • Que faire ?), , JPR report #3, 2000. Retrieved May 16, 2007.

- "This books treats several of the myths that have made antisemitism so lethal... In addition to these historic myths, we also treat the new, maliciously manufactured myth of Holocaust denial, another groundless belief that is used to stir up Jew-hatred." Schweitzer, Frederick M. & Perry, Marvin. Anti-Semitism: myth and hate from antiquity to the present, Palgrave Macmillan, 2002, (ISBN 0-312-16561-7), p. 3.

- "One predictable strand of Arab Islamic antisemitism is Holocaust denial..." Schweitzer, Frederick M. & Perry, Marvin. Anti-Semitism: myth and hate from antiquity to the present, Palgrave Macmillan, 2002, (ISBN 0-312-16561-7), p. 10.

- "Anti-Semitism, in the form of Holocaust denial, had been experienced by just one teacher when working in a Catholic school with large numbers of Polish and Croatian students." Geoffrey Short, Carole Ann Reed. Issues in Holocaust Education, Ashgate Publishing, 2004, (ISBN 0-7546-4211-9), p. 71.

- "Indeed, the task of organized antisemitism in the last decade of the century has been the establishment of Holocaust Revisionism – the denial that the Holocaust occurred." Stephen Trombley, "antisemitism", The Norton Dictionary of Modern Thought, W. W. Norton & Company, 1999, (ISBN 0-393-04696-6), p. 40.

- "After the Yom Kippur War an apparent reappearance of antisemitism in France troubled the tranquility of the community; there were several notorious terrorist attacks on synagogues, Holocaust revisionism appeared, and a new antisemitic political right tried to achieve respectability." Howard K. Wettstein, Diasporas and Exiles: Varieties of Jewish Identity, University of California Press, 2002, (ISBN 0-520-22864-2), p. 169.

- "Holocaust denial is a contemporary form of the classic anti-Semitic doctrine of the evil, manipulative and threatening world Jewish conspiracy." Introduction: Denial as Anti-Semitism « https://web.archive.org/web/20110604020743/http://www.adl.org/holocaust/theory.asp »(Archive.org • Wikiwix • Archive.is • Google • Que faire ?), , "Holocaust Denial: An Online Guide to Exposing and Combating Anti-Semitic Propaganda", Anti-Defamation League, 2001. Retrieved June 12, 2007.

- "In a number of countries, in Europe as well as in the United States, the negation or gross minimization of the Nazi genocide of Jews has been the subject of books, essay and articles. Should their authors be protected by freedom of speech? The European answer has been in the negative: such writings are not only a perverse form of anti-semitism but also an aggression against the dead, their families, the survivors and society at large." Roger Errera, "Freedom of speech in Europe", in Georg Nolte, European and US Constitutionalism, Cambridge University Press, 2005, (ISBN 0-521-85401-6), pp. 39-40.

- "Particularly popular in Syria is Holocaust denial, another staple of Arab anti-Semitism that is sometimes coupled with overt sympathy for Nazi Germany." Efraim Karsh, Rethinking the Middle East, Routledge, 2003, (ISBN 0-7146-5418-3), p. 104.

- "Holocaust denial is a new form of anti-Semitism, but one that hinges on age-old motifs." Dinah Shelton, Encyclopedia of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity, Macmillan Reference, 2005, p. 45.

- "The stress on Holocaust revisionism underscored the new anti-Semitic agenda gaining ground within the Klan movement. Holocaust denial refurbished conspiratorial anti-Semitism. Who else but the Jews had the media power to hoodwink unsuspecting masses with one of the greatest hoaxes in history? And for what motive? To promote the claims of the illegitimate state of Israel by making non-Jews feel guilty, of course." Lawrence N. Powell, Troubled Memory: Anne Levy, the Holocaust, and David Duke's Louisiana, University of North Carolina Press, 2000, (ISBN 0-8078-5374-7), p. 445.

- "Since its inception in 1979, the Institute for Historical Review (IHR), a California-based Holocaust denial organization founded by Willis Carto of Liberty Lobby, has promoted the antisemitic conspiracy theory that Jews fabricated tales of their own genocide to manipulate the sympathies of the non-Jewish world." Antisemitism and Racism Country Reports: United States « https://web.archive.org/web/20110628184616/http://www.tau.ac.il/Anti-Semitism/asw2000-1/usa.htm »(Archive.org • Wikiwix • Archive.is • Google • Que faire ?), , Stephen Roth Institute, 2000. Retrieved May 17, 2007.

- "There is now a creeping, nasty wave of anti-Semitism ... insinuating itself into our political thought and rhetoric ... The history of the Arab world ... is disfigured ... by a whole series of outmoded and discredited ideas, of which the notion that the Jews never suffered and that the Holocaust is an obfuscatory confection created by the elders of Zion is one that is acquiring too much, far too much, currency." Edward Said, "A Desolation, and They Called it Peace" in Those who forget the past, Ron Rosenbaum (ed), Random House 2004, p. 518.

- Conspiracy theory:

- "While appearing on the surface as a rather arcane pseudo-scholarly challenge to the well-established record of Nazi genocide during the Second World War, Holocaust denial serves as a powerful conspiracy theory uniting otherwise disparate fringe groups..." Introduction: Denial as Anti-Semitism « https://web.archive.org/web/20110604020743/http://www.adl.org/holocaust/theory.asp »(Archive.org • Wikiwix • Archive.is • Google • Que faire ?), , "Holocaust Denial: An Online Guide to Exposing and Combating Anti-Semitic Propaganda", Anti-Defamation League, 2001. Retrieved June 12, 2007.

- "Before discussing how Holocaust denial constitutes a conspiracy theory, and how the theory is distinctly American, it is important to understand what is meant by the term 'Holocaust denial.'" Mathis, Andrew E. Holocaust Denial, a Definition « https://web.archive.org/web/20110609180542/http://www.holocaust-history.org/denial/abc-clio/ »(Archive.org • Wikiwix • Archive.is • Google • Que faire ?), , The Holocaust History Project, July 2, 2004. Retrieved December 18, 2006.

- "Since its inception in 1979, the Institute for Historical Review (IHR), a California-based Holocaust denial organization founded by Willis Carto of Liberty Lobby, has promoted the antisemitic conspiracy theory that Jews fabricated tales of their own genocide to manipulate the sympathies of the non-Jewish world." Antisemitism and Racism Country Reports: United States « https://web.archive.org/web/20110628184616/http://www.tau.ac.il/Anti-Semitism/asw2000-1/usa.htm »(Archive.org • Wikiwix • Archive.is • Google • Que faire ?), , Stephen Roth Institute, 2000. Retrieved May 17, 2007

-

- "'Revisionism' is obliged to deviate from the standard method of historical pursuit because it seeks to mold facts to fit a preconceived result, it denies events that have been objectively and empirically proved to have occurred, and because it works backward from the conclusion to the facts, thus necessitating the distortion and manipulation of those facts where they differ from the preordained conclusion (which they almost always do). In short, "revisionism" denies something that demonstrably happened, through methodical dishonesty." McFee, Gordon. "Why 'Revisionism' Isn't" « https://web.archive.org/web/20100428044832/http://www.holocaust-history.org/revisionism-isnt/ »(Archive.org • Wikiwix • Archive.is • Google • Que faire ?), , The Holocaust History Project, May 15, 1999. Retrieved December 22, 2006.

- Alan L. Berger, "Holocaust Denial: Tempest in a Teapot, or Storm on the Horizon?", in Zev Garber and Richard Libowitz (eds), Peace, in Deed: Essays in Honor of Harry James Cargas, Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1998, p. 154.

Références

- Donald L Niewyk, The Columbia Guide to the Holocaust, Columbia University Press, 2000, p.45: « L'Holocauste est habituellement défini comme le meurtre de plus de cinq millions de Juifs par les Allemands pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale ». Les spécialistes avancent des estimations comprises entre 5,1 millions et 7 millions de morts.

- Margolin, Elaine. "The Post-War West Germans’ Post-Holocaust Distortions." Jewish Journal. 6 February 2014. 9 February 2015.

- Germany to open Holocaust archives Al-Jazeera 19 April 2006.

- Report of Earl G. Harrison. As cited in United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, "Resources," Life Reborn: Jewish Displaced Persons, 1945-1951

- The New York Times, 30 Sept. 1945, "President Orders Eisenhower to End New Abuse of Jews, He Acts on Harrison Report, Which Likens Our Treatment to That of the Nazis,"

- Robert L. Hilliard, "Surviving the Americans: The Continued Struggle of the Jews After Liberation" (New York: Seven Stories Press, 1997) p. 214

- Displaced Persons from the United States Holocaust Museum.

- Columbia University release

- Yad Vashem website

- Wistrich, R.S., Terms of Survival: The Jewish World Since 1945, Routledge, (ISBN 9780415100564, lire en ligne), p. 271

- Bolaffi, G., Dictionary of Race, Ethnicity and Culture, SAGE Publications, (ISBN 9780761969006, lire en ligne), p. 220

- "40% of Holocaust Survivors in Israel Live Below Poverty Line", Haaretz, December 29, 2005.

- "Social Safety Nets" (PDF), In Re Holocaust Victim Assets Litigation (Swiss Bank), September 11, 2000.

- « On Holocaust Remembrance Day, Israel's needy survivors still suffer », sur USA Today

- Jacobs, Neil G. Yiddish: A Linguistic Introduction, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2005, (ISBN 0-521-77215-X).

- David Shneer, Yiddish and the Creation of Soviet Jewish Culture: 1918-1930, Cambridge University Press, 2004. pp 13-14.

- David E. Fishman, The Rise of Modern Yiddish Culture, University of Pittsburgh Press, 2005. pp 84-85.

-

- Jan Schwarz, Survivors and Exiles: Yiddish Culture after the Holocaust, Wayne State University Press, 2015. עמ' 316.

- Solomon Birnbaum, Grammatik der jiddischen Sprache (4., erg. Aufl., Hamburg: Buske, 1984), p. 3.

- Hilberg 1996.

- Dawidowicz 1975, p. 403.

- Donald L. Niewyk et Francis R. Nicosia, The Columbia Guide to the Holocaust, Columbia University Press, , 45–46 p.

- https://www.chabad.org/multimedia/media_cdo/aid/1839019/jewish/Belief-in-G-d-After-the-Holocaust.htm

- « Poetry After Auschwitz: Is John Barth Relevant Anymore? »

- Paul Celan, « Fugue of Death » [archive du ] (consulté le )

- Michael J. Bazyler, Holocaust Justice: The Battle for Restitution in America's Courts, New York, NYU Press, (ISBN 9780814729380, lire en ligne), p. 202

- Lynn H. Nicholas, The Rape of Europa: The Fate of Europe's Treasures in the Third Reich and the Second World War, New York, Vintage Books, , 1st éd. (ISBN 9780307739728, lire en ligne), p. 43

- Michael J. Bazyler, Holocaust Justice: The Battle for Restitution in America's Courts, New York, NYU Press, (ISBN 9780814729380, lire en ligne), p. 204

- Jewish Virtual Library, Holocaust Restitution: German Reparations

- Der Spiegel, Holocaust Reparations: Germany to Pay 772 Million Euros to Survivors

- Le Monde, Pour le rôle de la SNCF dans la Shoah, Paris va verser 100 000 euros à chaque déporté américain

- Serge Klarsfeld, « Analysis of Statements Made During the June 20, 2012 Hearing of the U.S. Senate Committee of the Judiciary » [archive du ], sur Memorial de la Shoah, (consulté le )

- Harran, Marilyn. The Holocaust Chronicles, A History in Words and Pictures, Louis Weber, 2000, p. 697.

- « German TV Is Sanitizing History », Foreign Policy, (lire en ligne)

- « New Survey by Claims Conference Finds Significant Lack of Holocaust Knowledge in the United States », Claims Conference, (lire en ligne [archive du ], consulté le )pb - Maggie Astor, « Holocaust Is Fading From Memory, Survey Finds », The New York Times, (lire en ligne [archive du ], consulté le )

- Avi Marciano, « Vernacular politics in new participatory media: Discursive linkage between biometrics and the Holocaust in Israel », International Journal of Communication, vol. 13, , p. 277–296 (lire en ligne)

Annexes

Articles connexes

- Mémoire de la Shoah

- Antisémitisme secondaire

- Accord de réparations entre l'Allemagne fédérale et Israël (1952)

- Responsabilité de la Shoah (en)

Bibliographie

- Yehuda Bauer, Rethinking the Holocaust, New Haven, CT, Yale University Press, (ISBN 0-300-09300-4)

- (en) Lucy Dawidowicz, The War Against the Jews: 1933–1945, New York, Bantam, , Tenth Anniversary éd. (ISBN 0-553-34532-X)

- Raul Hilberg, The Politics of Memory: The Journey of a Holocaust Historian, Chicago, IL, Ivan R. Dee, (ISBN 1566631165)

- Peter Longerich, Heinrich Himmler, Oxford, Oxford University Press, (ISBN 978-0-19-959232-6, lire en ligne

)

) - Timothy Snyder, Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin, New York, Basic Books, (ISBN 978-0-465-00239-9)

- Bartrop, Paul R. and Michael Dickerman, eds. The Holocaust: An Encyclopedia and Document Collection (4 vol 2017)

- Gutman, Israel, ed. Encyclopedia of the Holocaust (4 Vol 1990)

- Sharon Kangisser Cohen, « What Now? Child Survivors in the Aftermath of the Holocaust » [archive du ], Jerusalem, Yad Vashem, (consulté le )

- Rossoliński-Liebe, Grzegorz. "Introduction: Conceptualizations of the Holocaust in Germany, Poland, Lithuania, Belarus, and Ukraine: Historical Research, Public Debates, and Methodological Disputes." East European Politics & Societies (Feb 2020) 34#1, pp 129–142.

- « A Changed World: The Continuing Impact of the Holocaust », sur United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, D.C.,