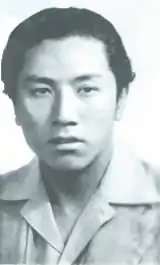

Phuntsok Wangyal

Phuntsok Wangyal (Goranangpa) tibétain : ཕུན་ཚོགས་དབང་རྒྱལ, Wylie : phun tshogs dbang rgyal, aussi Bapa Phuntsok Wangyal ou Phünwang (né le [1] à Bathang, district de Batang, actuelle préfecture autonome tibétaine de Garzê, Sichuan, et mort le à Pékin[2])[3], est un homme politique tibétain (Bapa ou Bapa est la désignation traditionnelle des habitants de Bathang)[4].

Il commença à militer dès l'école, fondant le Parti communiste tibétain en secret en 1939.

Arrêté en 1960 et incarcéré pendant 18 ans à la prison de Qincheng en République populaire de Chine, il fut libéré en 1978 et progressivement réhabilité.

Naissance à Bathang

Phuntsok Wangyal est né en 1922 à Bathang, petite ville de la province du Kham (Tibet oriental), à quelque 500 km à l'est de Lhassa, dans ce qui est maintenant le Sichuan oriental mais qui était à l'époque sous le contrôle du seigneur de guerre chinois Liu Wenhui[5].

Contexte politique

Au début du XVIIIe siècle, l'empire Qing établit un protectorat au Tibet, délimitant les frontières par le fleuve Drichu (Yangtsé supérieur) et Dzachu. Les Mandchous intègrent Bathang à la Chine, sans toutefois y exercer le pouvoir laissé aux chefs khampas. Au début du XXe siècle, ils décident d'intégrer le Kham et le Tibet central à la Chine, entraînant des résistances et des guerres. Quand le gouvernement tibétain reprend le Tibet central et une partie du Kham, Bathang reste sous contrôle chinois. L'effondrement de l'empire Qing laisse place à la République mais aussi aux seigneurs de la guerre[6].

Années de formation

Phuntsok Wangyal commence, à l'âge de quatre ans, son éducation monastique dans un monastère sous la conduite de son oncle, un moine réputé pour avoir fait ses études à Ganden. Mais ce dernier meurt subitement et, faute de tuteur, le jeune garçon doit quitter le monastère[6] - [7].

De l'âge de sept ans à l'âge de 12 ans, Phuntsok Wangyal est élève de l'école chinoise de Bathang, créée en 1907 par le gouvernement chinois et obligatoire pour les Tibétains. Il y étudie le chinois, le tibétain et les mathématiques. Un de ses camarades étant également élève dans l'école missionnaire chrétienne de Bathang, Phuntsok Wangyal apprend de celui-ci quelques chansons en anglais[8] - [9].

Selon A. Tom Grunfeld, Phunwang fréquente l'académie gérée par la commission des affaires mongoles et tibétaines de Tchang Kaï-chek à Bathang, école censée former les Tibétains pour qu’ils servent le gouvernement du Guomindang (GMD). À mesure qu’il avance dans ses études, Phunwang est de plus en plus déçu par le GMD et, n’ayant guère d’affinités, en tant que Khampa, avec le gouvernement tibétain à Lhassa, il s’intéresse à d’autres idéologies. Un de ses professeurs à l'académie lui prête des livres communistes russes, comme On Nationalities de Joseph Staline, dont la lecture l’amène à professer le communisme[10] - [11].

À 16 ans, Phuntsok Wangyal entre à l'école pour les minorités de Nankin. C'est là qu'il découvre les idées communistes au contact de ses camarades de classes et de certains professeurs. Selon Kim Yeshi, La lecture de Lénine et de Staline lui permet d'identifier l'oppression des Tibétains de Bathang, et les positions de ces auteurs sur le droit à l'identité et à l'autodétermination des minorités l'impressionnent[6].

Fondation du parti communiste tibétain (1939)

En 1939, avec cinq camarades il fonde clandestinement le parti communiste tibétain[12], tous s'engageant à consacrer leur vie à la révolution et la démocratie au Kham et au Tibet. Il est finalement exclu de l'école des minorités de Nankin en Chine où ses positions politiques déplaisent[6].

Phuntsok Wangyal voulait libérer Bathang, le Kham et toutes les régions tibétaines, du gouvernement nationaliste chinois et unifier le Tibet en une seule nation. Les Chinois ayant eu connaissance de son projet, il dût fuir au Tibet en traversant le Drichu. À Chamdo, il devint l'ami de Yuthok Tashi Dhondup, le gouverneur général du Kham, qu'il impressionna par ses idées progressistes et à qui il déclare que l'avenir du Tibet passait par une réforme de son système politique, la construction de routes, d'usines et des moyens modernes de production[6].

Selon A. Tom Grunfeld, ils passent la décennie suivante à essayer vainement de déclencher la révolution dans le Tibet oriental dans l’espoir de créer un grand Kham socialiste puis un grand Tibet socialiste[13].

Selon Tsering Shakya, la stratégie du petit parti communiste tibétain sous sa direction pendant les années 1940 est double : gagner les éléments progressistes parmi les étudiants et l'aristocratie du Tibet politique – le royaume du dalaï-lama – au programme de modernisation et de réforme démocratique, tout en soutenant une lutte de guérilla pour renverser dans le Kham le régime de Liu Wenhui, un des seigneurs de la guerre chinois. Son but est un Tibet indépendant unifié, et la transformation fondamentale de sa structure sociale féodale[14].

Quand le Guomindang est mis au courant, il lance un mandat d'arrêt contre Ngawang Kesang et lui-même et ils doivent s’enfuir au Tibet[15].

Selon Tsering Shakya, Phunwang voit d'un œil critique l'arrogance de certains membres de l'élite traditionnelle, la cruauté de certains moines rencontrés dans ses périples et la pauvreté des paysans – pire qu'en Chine – ployant sous les lourds impôts et le système des corvées[16].

En effet, à l'est du Drichu, le gouvernement chinois n'exerçait qu'un contrôle relâché en payant des fonctionnaires tibétains sans imposer sa présence dans le Kham. À l'ouest du Drichu, les fonctionnaires et les militaires tibétains mal payés pesaient sur les populations[6].

Il se rend à Lhassa où il rencontre d'autres communistes et Surkhang, membre du Khachag qui s’intéresse aux réformes dont Phuntsok Wangyal lui parle, mais ne peut initier de changement[6].

Quelques mois après son arrivée à Lhassa, fin 1943, il y est rejoint par son ami Ngawang Kesang, arrivant de Dartsedo[17].

En 1943, il se rend en Inde pour contacter le Parti communiste indien et chercher le moyen de rejoindre l'Union soviétique, un projet contrecarré par la Seconde Guerre mondiale.

En 1945, il retourne à Chamdo, y réunit des armes et des munitions pour expulser les Chinois et placer la région sous contrôle tibétain[6].

Selon la présentation éditoriale de la biographie de Phuntsok Wangyal, après son expulsion en 1940 et jusqu'en 1949, il a travaillé à organiser un soulèvement de guérilla contre les Chinois qui contrôlaient sa patrie[18].

En 1946, à Lhassa, Phuntsok Wangyal et Nganwang Kesang mettent en garde le gouvernement du Tibet de l'époque contre les risques d’une invasion par les communistes chinois, une fois la guerre civile terminée et en l’absence de changements au Tibet. La seule issue passe par l'aide de l’armée britannique. Le gouvernement ne leur prête aucune attention. Ils étaient inconnus et sans titre à l'époque. Phuntsok et Nganwang se rendent alors à Kalimpong, en Inde, pour rencontrer Gergan Dorje Tharchin, fondateur du Miroir du Tibet, un journal mensuel en tibétain qui informe l'élite tibétaine de ce qui se passe dans le monde. Phuntsok, qui souhaite rencontrer un représentant britannique, est mis en rapport par Tarchin avec sir Basil Gould à Gantok, à qui il remet une note personnelle de 12 pages, dont un exemplaire est envoyé à Lhassa. Comprenant que l’Angleterre fera la sourde oreille, Wangyal cherche l’appui des communistes indiens en contactant Jyoti Basu à Calcutta, mais les promesses de ce dernier sont vagues et non suivies d’effet »[19] - [20].

Après avoir soumis sa note personnelle, Phuntsok Wangyal dit en plaisantant à Tarchin : « Si le gouvernement tibétain ne m’écoute pas, j’amènerai l’armée chinoise au Tibet. Alors, je vous écrirai. » Au début de 1951, Tarchin reçoit un télégramme indiquant « Arrivé sain et sauf à Lhassa - Phuntsok Wangyal »[21].

Second séjour à Lhassa

À Lhassa, pendant une courte période, il donne des cours de chinois à l'école républicaine chinoise sise au Tromzikhang (en), dans le quartier du Barkhor[22]. Selon Robert Barnett, on lui permet également de tenir, sans révéler son engagement communiste, un salon non officiel d’intellectuels et d’aristocrates progressifs[23].

Expulsion des Chinois et de leurs sympathisants

Selon le témoignage de Phuntsok Wangyal lui-même, en , alors que les communistes chinois sont sur le point de gagner la guerre contre Tchang Kaï-chek, le Conseil des ministres du Tibet déclare qu'il est membre du parti communiste et l'expulse de Lhassa vers le Kham en passant par l'Inde, escorté de soldats tibétains. Les Chinois du gouvernement nationaliste sont également expulsés à la même période[24] ainsi que leurs sympathisants de Lhassa et du reste du Tibet sous l'administration du gouvernement tibétain[25].

Fusion du parti communiste tibétain avec le parti communiste chinois (1949)

Selon A. Tom Grunfeld, Phunwang et ses camarades abandonnent leur objectif d’un Tibet indépendant et font cause commune avec les communistes chinois[26]. Il rejoint la guérilla des communistes chinois contre le Kuomintang mais doit fusionner le Parti communiste tibétain avec le Parti communiste chinois de Mao Zedong à la demande des militaires chinois, et donc abandonner son projet d'un Tibet communiste indépendant autogouverné[27].

Rôle dans les négociations sur l'accord en 17 points (1951)

En 1951, Phuntsok Wangyal est interprète officiel chinois lors des négociations sur l'accord en 17 points sur la libération pacifique du Tibet entre Pékin et Lhassa[28]. Phunwang admet que ces négociations ont eu lieu sous la menace implicite de l'invasion du Tibet par les forces de l'Armée populaire de libération, mais il défend le document comme une solution raisonnable aux relations entre le Tibet et la Chine[29]. Non seulement il joue un rôle diplomatique décisif dans les tractations mais contribue à faire accepter l'accord par des membres de l'aristocratie tibétaine[30].

Rôle et activités au sein du parti communiste (1949-1957)

De retour dans sa ville natale, son engagement, ses capacités d’organisateur sont immédiatement repérées par le Front Uni si bien qu’au bout de quelques mois il est nommé membre du Comité de travail du Tibet, l’organisation qui régit le Tibet de 1951 à 1959, membre du Conseil politico-militaire du Sud-ouest, directeur du Département de la propagande militaire de la région et directeur adjoint du Front Uni du Tibet central[31].

Il joue un rôle administratif important dans l'organisation du parti à Lhassa et sert de traducteur au jeune 14e dalaï-lama pendant les célèbres rencontres de ce dernier avec Mao Zedong en 1954-1955, veillant entre autres à ce que le jeune homme de 19 ans n'aille pas danser le foxtrot avec les dames de la troupe de danse de l'État comme le faisaient les cadres du PCC[32]. Dans les années 1950, Phünwang est le responsable tibétain le plus haut placé du Parti communiste chinois[18].

La purge de 1957

Fin 1957, le dalaï-lama confie à Phuntsok Wangyal une lettre à l’attention du président Mao Zedong, d’autres envoyées précédemment étant restées sans réponse[33]. À Pékin, le dalaï-lama, qui a un grand respect pour Phuntsok Wangyal, demande qu’il soit nommé secrétaire du parti communiste chinois au Tibet[33] - [34]. Cette requête, présentée au général Chang Ching-wu, est acceptée, mais fin 1957, un fonctionnaire chinois informe le dalaï-lama que Phuntsok Wangyal ne reviendra plus au Tibet, car on le juge dangereux. On lui reproche principalement d’avoir fondé et organisé, lorsqu’il vivait dans le Kham, un parti communiste tibétain séparé[34]. En 1958, le dalaï-lama apprend que Phuntsok Wangyal a été déchu de son poste et mis en prison. Désolé de cette nouvelle, il en déduit que les dirigeants chinois de l’époque ne sont pas réellement des marxistes soucieux d’un monde meilleur, mais des nationalistes évoquant le chauvinisme Han[34].

Selon Robert Barnett, dès 1957, Phuntsok fait les frais d’une purge lors de la campagne anti-droitiste ayant pour cible les dirigeants du Front Uni et leur chef Li Weihan[35].

Années de détention (1958-1978)

Bien que Phuntsok Wangyal parlât chinois couramment, que la culture chinoise lui fût familière et qu'il fût dévoué au socialisme et au Parti communiste, son engagement profond pour le bien-être des Tibétains le rendit suspect aux yeux de puissants collègues Han[18] - [36].

En 1958, qualifié de « nationaliste local » (expression désignant une personne plaçant les intérêts d'un groupe ethnique avant ceux de l'État), Phuntsok Wangyal est confiné, ou mis au secret[18], à Pékin. En 1960, à la suite du soulèvement tibétain de 1959, il est emprisonné à la prison de Qincheng à Pékin. Il y passe 18 années en isolement cellulaire[37].

Selon la politologue indienne Swarn Lata Sharma, tous les membres de sa famille, y compris sa fille âgée de 2 ans furent mis en prison. Sa femme y est morte. Il fut maintenu dans un isolement tel qu’il ignorait avant sa libération que son frère avait été incarcéré dans la même prison que lui pendant 14 ans[38].

Selon Kim Yeshi, pour détruire leur volonté et leur moral, les prisonniers politiques ont été soumis à diverses tortures physiques et psychiques en Chine. Comme Phuntsok Wangyal s'inquiétait pour ses enfants, des bébés en pleurs furent placés sous sa fenêtre. Les gardiens crachaient dans sa nourriture et venait le passer à tabac la nuit. On lui administrait une substance qui lui provoqua des acouphènes[6]. Il eut plusieurs accès de folie. La pire des tortures dont il se souvient fut d'être bombardé d'« ondes électroniques » dans sa cellule, ce qui lui occasionna d'atroces migraines. Les mois qui suivront sa libération, il ne pourra pas s'empêcher de baver[39].

Phuntsok s'est marié à une Tibétaine musulmane[33]. Pour obtenir la permission de l'épouser, il s'était converti, sans grande difficulté, étant plus marxiste que bouddhiste[40]. Son épouse est décédée alors qu'il était en prison. Quand ses enfants rendirent visite à leur père en hôpital psychiatrique en 1975, il n'osèrent pas lui dire qu'elle avait eu une mort effroyable quelques années plus tôt[6]. Elle avait préféré se suicider[29].

Libération et réhabilitation (1978)

En 1978, il est libéré mais reste à Pékin sans contact avec l'extérieur pendant plusieurs années[41] - [42]. Plus tardivement, il retourna fréquemment au Tibet[43].

Progressivement réhabilité[44], il occupe de hauts postes mais de nature surtout honorifique[45].

Il vit dans une résidence pour hauts responsables gouvernementaux à la retraite[46].

Il est resté fidèle à ses idéaux socialistes, Phuntsok est convaincu que la pensée de Lénine et de Staline peut être bénéfique au développement de la société tibétaine[47].

Rencontre avec la délégation tibétaine du gouvernement tibétain en exil de 1979

En 1979, Phuntsok Wangyal qui n'occupait alors qu'un modeste poste administratif sans grand pouvoir, rencontra les membres de la première mission d'enquête au Tibet du dalaï-lama (entre le et le ), en visite en Chine et au Tibet, dont Juchen Thupten Namgyal[48]. La délégation, composée de cinq personnes, était conduite par Lobsang Samten[49]. Au cours de ses conversations avec les membres de la délégation, il déclara qu'il rendait responsables de son emprisonnement non pas le parti communiste mais des gens qui avaient enfreint les lois, violé la discipline du parti et les lois du pays[50].

Lettres à Hu Jintao et à Xi Jinping

Dans les années 2000, Phuntsok Wangyal a écrit plusieurs lettres à Hu Jintao. Aucune de ces lettres n'avait toutefois été rendue publique avant quand l'agence Reuters en obtint des copies par deux sources proches de Wangyal[51] - [52]. Elles ont été publiées courant 2007 par les éditions Paljor Publications, une branche de la Library of Tibetan Works and Archives (Dharamsala), dans un ouvrage intitulé Witness to Tibet’s History[53].

En 2004, il écrit notamment une lettre importante à Hu Jintao et au directeur du Centre de recherche tibétologique de Chine et porte parole tibétain nommé par l'Etat Lhagpa Phuntshogs où il exhorte Pékin à dialoguer au plus vite avec le dalaï-lama et à autoriser son retour au Tibet. Il explique que cela ne concerne pas seulement l'harmonie et le développement durable des régions tibétaines, mais aussi tous les groupes ethniques. Sa requête n'a pas été entendue[54].

Lettre de 2004

Dans sa lettre du , il espère infléchir la politique chinoise[55] et écrit : « [...] quand le gouvernement central et le Dalaï Lama auront atteint un stade de compréhension mutuelle sur les principes de la souveraineté nationale, des ajustements appropriés à la politique de répartition administrative et sur l'application du droit à l’autodétermination, les deux parties devraient déclarer dans un rapport politique officiel que des relations amicales ont été restaurées entre eux »[56]. Il a aussi écrit que Hu Jintao devrait permettre le retour du dalaï-lama au Tibet, suggérant que cela serait « [...] bien pour stabiliser le Tibet ».

Lettre de 2006

Dans une 3e lettre, datée du , il a écrit : « Si la solution de la question du Tibet continue à être retardée, il est tout à fait probable que cela aboutira à la création d'un "Vatican oriental du bouddhisme tibétain" à côté du Gouvernement tibétain en exil. La "question du Tibet", au niveau national ou international, deviendra alors plus compliquée et plus dérangeante »[57].

Lettre de 2007

Selon le site TibetInfoNet, dans une lettre adressée en 2007 au président Hu Jintao, Phuntsok Wangyal critiqua les faucons du Parti communiste chinois qui, rivalisant pour soutenir les adeptes de Dordjé Shugden, « gagnent leur vie, sont promus et s'enrichissent en s'opposant au séparatisme »[58].

Dans une de ces lettres qui lui sont attribuées, Phuntok Wangyal note que le Tibet dépend de l'aide fournie par le gouvernement central et les autres provinces et villes du pays pour 95 % de ses ressources financières et que cette assistance englobe l'aide financière directe ainsi que l'assistance au développement économique[59].

Lettre de 2011

En , il écrit une lettre à Xi Jinping, qui sera publiée en 2013 en tibétain dans un ouvrage comportant certains de ses écrits publiés par le Centre culturel tibétain Khawa Karpo à Dharamsala[60].

Accueil critique

Billy Wharton (en), rédacteur en chef de The Socialist, magazine du Parti socialiste des États-Unis, fit une lecture critique de ses mémoires. Pour lui, l'ouvrage peut servir à dissiper les mythes qui circulent à la fois dans le camp pro-tibétain et celui pro-chinois. L'argument de Phunwang concernant les droits à l'autodétermination comme le préconise la tradition léniniste est convaincant et met en évidence la dérive générale de la révolution chinoise. Mais surtout, Phunwang illustre la manière dont les politiques conçues au cours de la période ultra-gauche de 1957-1976 ont continué à être employées par le PCC. Pris ensemble, ces arguments portent gravement atteinte à l'affirmation chinoise selon laquelle le mouvement tibétain est produit par les agitations des exilés[29].

La revendication indépendantiste pro-tibétaine n'est en rien facilitée par le témoignage de Phünwang. Celui-ci indique de façon tout à fait explicite que dans les années 1950, le désir ou l'exigence d'indépendance se faisaient entendre uniquement dans les secteurs les plus conservateurs de l'aristocratie religieuse et économique tibétaine. Selon Billy Wharton, pour Phunwang, le dalaï-lama reste une figure centrale de la résolution du conflit entre le Tibet et la Chine : « Il n'y a pas de raison d'avoir des soupçons concernant les intentions du dalaï-lama, et aucune raison de fausser sa pensée sincère et altruiste et d'attaquer son caractère incomparable »[29].

Sa mort

À sa mort le , le 14e dalaï-lama adresse un message de condoléance à sa femme et ses enfants, qualifiant Phuntsok Wangyal de vrai communiste, sincérement motivé pour réaliser les intérêts du peuple tibétain, regrettant de n'avoir pu le revoir[2].

Œuvre

- Liquid Water Does Exist on the Moon, Beijing, China, Foreign Languages Press, 2002, (ISBN 7-119-01349-1)

- Witness to Tibet's History, édité par Jane Perkins, avant-propos de Kasur Sonam Topgyal, préface de Serta Tsultrim, traduit par Tenzin Losel, New Delhi, Paljor Publication, 2007, (ISBN 81-86230-58-0)

Notes et références

- (en) Veteran Tibetan Communist Phunwang dies, Dalai Lama expresses grief

- (en) Condolence Message from His Holiness the Dalai Lama at the Passing Away of Baba Phuntsog Wangyal, uspolitics.einnews.com, 30 mars 2014

- « Tibetan Communist who urged reconciliation with Dalai Lama dies », Daily News and Analysis, Reuters, Beijing, Chine, (consulté le )

- (en) Robert Barnett, The Babas are Dead: Street Talk and Contemporary Views of Leaders in Tibet, in Proceedings of the International Association of Tibetan Studies (ed. Elliot Sperling), University of Indiana, Bloomington, p. 5 : « Babas are Tibetans from Bathang, the town in eastern Kham on the main route that runs through western Sichuan (or Xikang, as it was known between 1935 until 1955 when it was a separate province) to the eastern border of central Tibet ».

- (en) Tsering Shakya on Melvyn Goldstein et al, A Tibetan Revolutionary. Memoirs of an indigenous Lenin from the Land of Snows, and his long imprisonment by the Mao government : « Phünwang was born in 1922 in Batang, a small town—‘remote and beautiful’—in the Kham province of Eastern Tibet, some 500 miles east of Lhasa in what is now eastern Sichuan, then under the control of the Chinese warlord Liu Wenhui. »

- Kim Yeshi, Tibet. Histoire d'une tragédie, Édition La Martinière, février 2009, chapitre sur Phuntsok Wangyal (p 200-207) - (ISBN 978-2-7324-3700-2).« En 1975, on le transféra dans un hôpital psychiatrique où il rencontra ses enfants. Il ne les avait pas vu depuis quinze ans et ceux-ci ignoraient que leur père était toujours vivant [...] Ils ne lui dire pas qu'ils avaient eux aussi terriblement souffert et que leur mère avait connu une mort effroyable quelques années plus tôt. »

- (en) Melvyn Goldstein, Dawei Sherap, William Siebenschuh, A Tibetan Revolutionary. The political life of Bapa Phüntso Wangye, University of California Press, 2004, p. 7.

- (en) Melvyn Goldstein, Dawei Sherap, William Siebenschuh, op. cit., p. 8.

- Roland Barraux, op. cit., p. 336.

- (en) A. Tom Grunfeld, compte rendu de A Tibetan Revolutionary: The Political Life and Times of Bapa Phuntso Wangye (Melvyn C. Goldstein, Dawei Sherap, and William R. Siebenschuh), in China Review International, Vol. 11, 2004, pp. 351-354 : « As a child Phunwang attended a Chinese government-sponsored school in Batang that had been established to prepare ethnic Tibetans for work in the Guomindang (GMD) government. As his education progressed Phunwang became increasingly disillusioned with the GMD and, coupled with a traditional Khampa (a person from Kham) disenchantment with the Tibetan government in Lhasa, he sought alternative ideologies. It was one of his teachers who introduced Phunwang to socialist ideas, lending him Russian communist books such as Joseph Stalin's On Nationalities, and it wasn't long before Phunwang had embraced communism ».

- Tserin Shakya, The Prisoner, in New Left Review, July-August 2005 : « It was a teacher, Mr Wang, at the special academy run by Chiang Kaishek’s Mongolian and Tibetan Affairs Commission, who first introduced the sixteen-year-old Phünwang to Lenin’s Nationality and the Right to Self-Determination ».

- (en) A. Tom Grunfeld, op. cit. : « He founded the Tibetan Communist Party in 1939 along with five comrades. »

- (en) A. Tom Grunfeld, op. cit. : « they spent the next decade in a vain attempt to spark a revolution in eastern Tibet in the hopes of creating a greater socialist Kham, and ultimately a greater socialist Tibet. »

- (en) Tsering Shakya, The prisoner, New Left Review, 34, July-August 2005 : « The strategy of the tiny Tibetan Communist Party under his leadership during the 1940s was twofold: to win over progressive elements among the students and aristocracy in ‘political Tibet’— the kingdom of the Dalai Lama — to a programme of modernization and democratic reform, while building support for a guerrilla struggle to overthrow Liu Wenhui’s rule in Kham. The ultimate goal was a united independent Tibet, its feudal social structure fundamentally transformed ».

- Melvyn C. Goldstein, Dawei Sherap, William R. Siebenschuh, Political Life and Times of Bapa Phüntso Wangye, op. cit. : « The minute they learned this, the GMD formally issued a warrant for the arrest of Ngawang Kesang and myself. At that point, we knew we couldn’t stay in Sadam much longer. We had to go back into Tibet proper, where the Chinese could not get us. »

- (en) Tsering Shakya, The prisoner, New Left Review, 34, July-August 2005 : « Phünwang gives a lively critical account of the arrogance of certain members of the traditional elite, the cruelty of some of the monks he encountered during his travels and the poverty of the peasants — worse than in China itself — under the heavy taxes and corvée labour system. »

- Melvyn C. Goldstein, Dawei Sherap, William R. Siebenschuh Political Life and Times of Bapa Phüntso Wangye, op. cit., p. 70 : « Then a few months later, at the end of 1943, my trusted comrade Ngawang Kesang arrived on business from Tartsedo, and soon afterward we decided to rename our revolutionary organization to better fit the situation in Lhasa, »

- (en) Biography of a Tibetan Revolutionary Highlights Complexity of Modern Tibetan Politics, Phayul.com 19 juin 2004. voir aussi A Tibetan Revolutionary: The Political Life and Times of Bapa Phüntso Wangye, University of California Press « According to the University of California Press, "[...]. He was expelled in 1940, and for the next nine years he worked to organize a guerrilla uprising against the Chinese who controlled his homeland. »

- (en) Tsering Shakya, The dragon in the land of snows: a history of modern Tibet since 1947, 1999, p. 10 : « He came to Lhasa in 1946 and tried to warn the Lhasa authorities that after the civil war the Communists would invade Tibet. »

- Thubten Samphel, op. cit. : « in 1946, two visitors from Tibet landed at Tharchin Babu's doorstep: Baba Phuntsog Wangyal and his friend. (...) Earlier the two had visited Lhasa to warn the Tibetan government that unless it brought about changes in Tibet, the country would succumb to an imminent Chinese invasion after the Chinese civil war. (...) They warned Lhasa that the only way out was to obtain British military aid. The two said Lhasa had ignored them. They were 'nobody', had no names, no titles. So they came to Kalimpong in the hope of directly approaching the British government in India. Tharchin Babu travelled with them to Gangtok and introduced them to Sir Basil Gould, the British Political Officer (...). The 12-page memorandum, which Baba Phuntsog Wangyal wrote, was transmitted to London through the office of the Political Officer. A copy was sent to Lhasa. Realising Britain would ignore his pleas for help, Baba Phuntsog Wangyal made a trip to Calcutta and met with Jyoti Basu for Indian communist help in securing arms. But his promises of help then were vague and in the end not forthcoming. »

- (en) Thubten Samphel, Virtual Tibet: The Media, in Exile as challenge: the Tibetan diaspora (sous la direction de Dagmar Bernstorff, Hubertus von Welck), Orient Blackswan, 2003, 488 pages, en part. pp. 172-175 (ISBN 81-250-2555-3 et 978-81-250-2555-9).

- (en) Hartley, Lauren R.,Schiaffini-Vedani, Patricia, Modern Tibetan literature and social change, Durham, Duke University Press, , 382 p., poche (ISBN 978-0-8223-4277-9, LCCN 2007047887, lire en ligne), p. 37 : « The Republican school started enrolling students in 1938 and was in the Tromzikhang, on the north side of the Barhor. The staff comprised Chinese, Hui, and Tibetan teachers. Baba Püntsok Wanggyel, a progressive pro-Communist Tibetan from Batang (Kham), also taught for a short period in that school. »

- Robert Barnett, op. cit., p. 7 : « In the late 1930s and early 1940s he had tried to establish a communist party among Tibetans in Kham, but later had to flee to Lhasa, where he had been allowed to teach Chinese and to head, without revealing his commitment to communism, an informal salon of progressive intellectuals and aristocrats ».

- Melvyn C. Goldstein, Dawei Sherap, William R. Siebenschuh Political Life and Times of Bapa Phüntso Wangye, op. cit. : « From the newspaper articles, it was becoming clearer that the Chinese communists were eventually going to win the war against Chiang Kaishek, and the Tibetan government was becoming increasingly nervous about the prospect that the atheist socialists would soon rule China. [...] One day in July 1949, I answered a knock at the door to find the lay official Changöpa together with another lay official, a monk official, and about nine or ten armed Tibetan soldiers. With the soldiers standing by and Changopa, who had been to England, taking photographs, the monk official read a formal letter from the Council of Ministers stating that I was a member of the Communist Party and had to leave Lhasa within three days. [...] The officials just listened, and then told me that I had to go back to Kham through India (not Tibet) and that they would send soldiers to accompany me. [...] Li and the others in the Nationalist Government office had also been expelled and were preparing to leave themselves via India. »

- Robert Barnett, op. cit., p. 7 : « he had been forced to return to his hometown when the declaration of the PRC in July 1949 led the Tibetan government to expel all Chinese and their sympathisers from Lhasa and from as much of Tibet as it administered. »

- A. Tom Grunfeld, op. cit. « It was only in 1949 that he and his fellow Tibetan communists abandoned their goal for an independent Tibet and joined up with the Chinese communists ».

- Tsering Shakya, op. cit. : « Forced to abandon his goal of ‘self-rule as an independent communist Tibet’ ».

- (en) ‘Agreement on Measures for the Peaceful Liberation of Tibet’ or the ‘17-Point Agreement’, Context and Consequences, Department of Information and International Relations, Dharamsala - 2001.

- (en) Billy Wharton, (editor of The Socialist, monthly magazine of the Socialist Party USA), MEMOIRS OF A TIBETAN MARXIST. Middle Ground Between Mao and the Dalai Lama?, World War Report 4.

- Tsering Shakya, op. cit. : « He played a key diplomatic role in negotiations over the Seventeen-Point Agreement between Beijing and Lhasa, and in winning acceptance for it from members of the Tibetan aristocracy ».

- Robert Barnett, op. cit., p. 7 : « Back in Bathang his organisational skills and commitment were immediately recognised by the United Front, so that within months he had been appointed to the 15-member Tibet Working Committee, the shadow body that in reality controlled Tibet for nine years after the 1950 invasion. (…). Phuntsog Wangyal was also placed on the South-west Military-Political Council, appointed a director of the Military Propaganda Department in the region, and named as a deputy director of the United Front in Central Tibet. »

- Tsering Shakya, op. cit. : « Phünwang was the trusted translator for talks between Mao and the 19-year-old Dalai Lama in Beijing in 1956 (taking it as his duty to make sure the boy did not get up to dance the foxtrot with the ladies of the State Dance troupe, as the ccp cadres liked to do). »

- Roland Barraux - "Histoire des Dalaï Lamas - Quatorze reflets sur le Lac des Visions", Albin Michel, 1993. Réédité en 2002, Albin Michel, (ISBN 2226133178).

- Dalaï Lama, Au loin la liberté, autobiographie, Livre de poche, 1993 (ISBN 225306498X).

- Robert Barnett, op. cit., p. 8 : « by 1957 Phuntsog Wangyal had been purged, an early victim of the anti-Rightist campaign and its particular targetting of the United Front leadership under Li Weihan ».

- (en) « Though he was fluent in Chinese, comfortable with Chinese culture, and devoted to socialism and the Communist Party, Phünwang's deep commitment to the welfare of Tibetans made him suspect to powerful Han colleagues. »

- (en) Jeff Bendix, op. cit. : « In 1958 he was labeled a "local nationalist" (someone who put the interests of his ethnic group above the interests of the state) and ordered to remain in Beijing. Two years later, following the Tibetan uprising against the Chinese, he was arrested and spent the next 18 years in solitary confinement ».

- (en) Swarn Lata Sharma, Tibet, self-determination in politics among nations, 1988, Criterion Publications, 1988, p. 193 : « Mr Phuntsok Wangyal — one of the first Tibetan communists to collaborate with the Chinese had been put in prison in 1957 because he had opposed their treachery in Tibet. Every member of his family including his two years old daughter was put in prison. His wife died there and since he was released only about a year and a half ago, he said he found it very difficult to speak in Tibetan because he had never been allowed to talk during his imprisonment. He was kept in such isolation that he did not know until released that his brother had been in the same prison for fourteen years. »

- Tsering Shakya, op. cit. : « When he was finally released from the ‘Beijing Bastille’, after several periods of insanity, he was fifty-seven. The worst of many tortures he recalled was being bombarded by ‘electronic waves’ in his cell, which produced excruciating headaches. For months after his release he could not stop himself drooling ».

- (en) Hisao Kimura, Scott Berry, Japanese agent in Tibet: my ten years of travel in disguise, Serinda Publications Inc, 1990, p. 206 : « Her only objection to my friend was that he was not of their faith. More of a Marxist than a Buddhist anyway, Phuntsok Wangyel found a change of religion no great problem, and he quickly arranged to meet four Muslim elders of Wobaling to undergo the necessary initiation ceremony. »

- Fabienne Jagou, compte rendu de A Tibetan Revolutionary. The Political Life and Times of Bapa Phüntso Wangye, Lectures critiques, in China perspectives, No 58 (march-april 2005).

- Claude Arpi, Le dernier caravanier. La vie d’Abdul Wahid Radhu, La Revue de l'Inde, no 7 (2007).

- (en) Jeff Bendix Case anthropologist tells story of Tibet Communist Party founder, New book is oral history, autobiography titled "A Tibetan Revolutionary", July 2, 2004 : « After his release he was rehabilitated and continues to live in Beijing, although he frequently visits Tibet ».

- Jeff Bendix, op. cit. : « Finally, in 1978, Phunwang was released from prison and gradually rehabilitated in the Chinese Communist Party ».

- Robert Barnett, op. cit., p. 8 : « even when finally released in 1978 he had to remain in the Chinese capital, fulfilling senior but largely honorary positions, some of which he still holds ».

- Jeff Bendix, op. cit. : « he lives in a residence of retired high government officials. »

- Fabienne Jagou, op. cit. : « Today, Phünwang is still faithful to his socialist ideals and convinced that the thinking of Lenin and Stalin may benefit the development of Tibetan society. »

- Claude Arpi, Interview with Kasur Thubten Juchen Namgyal, 15 mars 1997.

- Stéphane Guillaume, La question du Tibet en droit international, p. 52.

- (en) Andy Newman, Phüntso Wangye - The Tragdy of Tibet's First Communist, Socialist Unity, 1 April, 2008 : « In 1979, in a conversation with a delegation sent by the Dalai Lama, Phuntso Wangye declared, “I was and am still a communist who believes in Marxism… I am a communist, true, but I was also in solitary confinement in a communist prison for as long as 18 years and suffered from both mental and physical torture” but then he does not blame party, at all, rather he says, “I was put into prison by people who broke the laws and violated party discipline and the laws of the country.” »

- (en) Hawks blocking Dalai Lama’s return, TibetInfoNet (TIN), 7 mars 2007 : « Phuntsog Wangyal, the 84-year-old Tibetan Communist veteran, has written to President Hu Jintao and condemned "hawks" for blocking the Dalai Lama's return and criticised them as they "make a living, are promoted and become rich by opposing splittism". Phuntsog Wangyal's three letters to Hu have never been made public, however, Reuters has obtained copies of the letters ».

- (en) Former Tibetan Communist official asks Hu to allow return of the Dalai Lama, The New York Times, 7 mars 2007

- Witness to Tibet's History.

- (en) Tsering Woeser, Wang Lixiong, Tibetans are ruined by hope, in Voices from Tibet: Selected Essays and Reportage, traduit par Violet Law, Hong Kong University Press, 2014, (ISBN 988820811X et 9789888208111), p. 15

- Tibet, otage de la Chine Claude B Levenson,

- (en) CTA's response to Chinese government allegations: Part One, 15 mai 2008 : « [...] after the Central Government and the Dalai Lama have reached a mutual understanding on the principles regarding national sovereignty, appropriate adjustments to the domestic administrative division policy and implementing the right to self-determination, both sides should officially declare in a political statement that friendly relations between them have been restored. ».

- (en) Baba Phuntsok: Witness to Tibet's History, Where Tibetans Write, 26 décembre 2007 : « [...] Hu should welcome back the Dalai Lama to Tibet which Phunwang suggests will be "…good for stabilizing Tibet". In his Third Letter of August 1 2006, Phunwang writes: "If the inherited problem with Tibet continues to be delayed, it is most likely going to result in the creation of ’The Eastern Vatican of Tibetan Buddhism’ alongside the Exile Tibetan Government. Then the ’Tibet Problem’, be it nationally or internationally, will become more complicated and more troublesome." »

- (en) Allegiance to the Dalai Lama and those who "become rich by opposing splittism", TibetInfoNet (TIN), 7 mars 2007 : « The worship of the deity has the ostensible support of both the regional and central party leadership, which have been generous with both financial and administrative support to the pro-Shugden groups and programmes. The rush in championing the Shugden cause gives those cadres supporting it privileged access to funds and enhances their personal stature. In a recently publicised letter to Chinese president Hu Jintao, Communist Party veteran Phuntsog Wangyal spoke of these cadres as people who "make a living, are promoted and become rich by opposing splittism" ».

- (en) Hui Wang, Theodore Huters, The Politics of Imagining Asia, 2011, 368 p., p. 197 : « In a letter he wrote to Hu Jintao, the first-generation Tibetan revolutionary, Phuntsok Wangyal, noted that Tibet depended upon aid from the central government and from the provinces and other cities for 95 % of its financial resources, (93) and that this assistance includes direct financial aid as well as assistance for Tibetan economic development. Note 93 : Phuntsok Wangyal [...], "Xiegei Hu Jintao de Xin" (A letter written to Hu Jintao, http://www.washeng.net.) »

- (en) Bawa Phuntsok Wangyal Book Launch, Voice of America, 19 septembre 2013.

Voir aussi

Bibliographie

- Melvyn Goldstein, Dawei Sherap, William Siebenschuh, A Tibetan Revolutionary. The political life of Bapa Phüntso Wangye, University of California Press, 2004

- Kim Yeshi, Tibet. Histoire d'une tragédie, Édition La Martinière, , chapitre sur Phuntsok Wangyal (p. 200-207) - (ISBN 978-2-7324-3700-2).

Articles connexes

- Parti communiste tibétain

- Liste de prisonniers d'opinion tibétains

- Gu-Chu-Sum Mouvement du Tibet (association d'anciens prisonniers politiques tibétains)

Liens externes

- Première lettre de Phuntsok Wangyal à Hu Jintao en octobre 2004

- Baba Phuntsok: Witness to Tibet’s History Book Release: October 26 2007, Lhakpa Tsering Hall, DIIR, Dharamsala, INDIA