Quatre Tibétains de Rugby

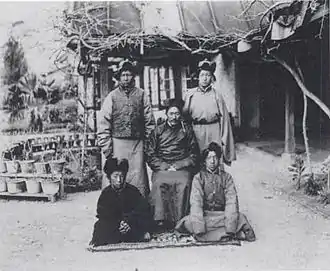

Les « quatre Tibétains de Rugby » (« the four Rugby boys ») sont, dans les années 1910, quatre jeunes Tibétains[1] qui devaient être éduqués dans la public school de Rugby en Grande-Bretagne puis suivre une formation professionnelle dans un domaine scientifique ou technique particulier avant de rentrer au Tibet[2] afin de constituer l'avant-garde des modernisateurs du pays. Lungshar, un conseiller du 13e dalaï-lama, avait été chargé d'accompagner, en 1913, ces quatre jeunes gens (W. N. Kyipuk, K. K. Möndro, S. G. Gokharwa et R. D. Ringang). Ayant appris beaucoup lui aussi lors de son séjour, il modernisa l'armée à son retour[3].

Pour Lhalu Tsewang Dorje, un des fils de Lungshar, « l'expérience ne [fut] pas un franc succès »[4], pour l'historien Peter Hopkirk, elle fut une réussite partielle[5]. Pour Robert W. Ford, un opérateur radio britannique au Tibet, Ringang est le seul qui eût réussi au Tibet, en construisant une station hydroélectrique et une ligne électrique jusqu'à Lhassa[6]. Pour l'historien Alastair Lamb, les jeunes diplômés furent par la suite incapables ou empêchés de contribuer de façon notable au développement du Tibet[7].

Selon le 14e dalaï-lama, ils firent un excellent travail à leur retour. L'un (Ringang) mit en place un réseau électrique dans une partie de Lhassa, et un autre (Kyipup) une liaison télégraphique entre Gyantsé et Lhassa[3].

L’expérience

En , le 13e dalaï-lama demanda à ce qu’un certain nombre de « fils de bonne famille, vigoureux et intelligents », reçoivent une éducation hors pair en Angleterre. Les jeunes gens choisis se retrouvèrent à l’agence commerciale britannique à Gyantsé, accompagnés d’un de ses conseillers, Lungshar. Il s’agissait de W. N. Kyipup, âgé de 16 ans, K. K. Möndro (un moine), 17 ans, S. G. Gokharwa, 16 ans, et R. D. Ringang, 11 ans. Le gouvernement indien décida que Basil Gould, qui était sur le point de rentrer en Angleterre, les accompagnerait pendant la durée du trajet et les aiderait pendant les premières semaines de leur séjour en Angleterre en [8].

Lungshar était aussi accompagné de sa femme, de Laden La, un policier sikkimais, et du fils de ce dernier, Sonam Topge[9], et de deux serviteurs.

Dès le départ, les Britanniques trouvèrent Lungshar plutôt embêtant. Alors qu'en théorie il n'était guère plus que le chaperon des enfants, dans les faits il se considérait comme ambassadeur tibétain itinérant[10].

Le , Lungshar fut reçu, avec les quatre garçons, par le roi George V et la reine Mary de Teck, ainsi que par les principaux ministres. Il leur remit des cadeaux de la part du 13e dalaï-lama et en reçut en échange[11] - [12].

Les quatre jeunes Tibétains s’installèrent à Farnham, dans le Surrey, où ils commencèrent à apprendre l’anglais sous la houlette de l’école Berlitz tandis que l'épouse de Lungshar parvenait à séduire l'un d'entre eux[13], Gongkar[14]. Après avoir exclu les écoles de Harrow, Eton et Wellington, et le collège de Cheltenham (lequel devait accueillir trois fils du président chinois Yuan Shikai), leurs hôtes britanniques décidèrent de les envoyer étudier à Rugby[15].

W. N. Kyipup

Né en 1896, Wangdu Norbu Kyipup avait étudié la télégraphie, l'arpentage et la cartographie et, à son retour au Tibet en 1917, s'était vu confier la tâche de développer le réseau télégraphique. Martin Brauen précise qu'il installa une ligne télégraphique entre Gyantsé et Lhassa, permettant au Tibet de communiquer avec le reste du monde[16]. Selon Lhalu Tsewang Dorje, il n'aurait pas réussi dans les télégraphes, et fut affecté au poste de magistrat ou maire de Lhassa, à celui de chef de la police. Il servit aussi au Bureau des Affaires étrangères du Tibet, où il aurait notamment fait office d'interprète et de guide pour les visiteurs anglophones, et il lut aussi les nouvelles en tibétain à Radio Lhassa[17].

K. K. Möndro

Né en 1897, Khenrab Kunzang Möndro étudia l'ingénierie minière aux houillères de Grimethorpe (en) dans le sud du Yorkshire, et la minéralogie à Camborne dans les Cornouailles. À son retour en 1917, il se lança dans la prospection minière[12]. Accusé de déranger les esprits et de gâter les récoltes, il finit par renoncer[18]. Cependant, en 1922, il se remit à chercher de l'or au Tibet avec un Britannique, sir Henry Hubert Hayden (1869–1923), dont l'intervention avait été sollicitée par le gouvernement tibétain pour la prospection de mines[12]. Il devint ensuite l'interprète personnel du 13e dalaï-lama et occupa, en 1923[12], le poste de chef de la police de Lhassa[19]. Plus tard cependant, il fut rétrogradé au niveau d'agent de sixième rang et envoyé à Ngari comme dzongpön de Rudok[12]. En 1930, il fut rappelé à Lhassa pour représenter les habitants de Rudok. Il fut également conservateur des objets sacrés au Norbulingka et au Potala et nommé mipön (maire) du village de Shöl[12].

S. G. Gokharwa

Sonam Gompo Gokharwa (ou Gongkar) alla à l'académie militaire de Woolwich puis suivit une formation d'officier auprès de l'armée de l'Inde britannique car on comptait sur lui pour réorganiser l'armée tibétaine. Pour des raisons politiques, il fut affecté à un poste frontière du Kham[20]. Selon David Macdonald, Gongkar serait tombé amoureux d'une jeune Anglaise et aurait voulu l'épouser mais permission de convoler en justes noces lui aurait été refusée par le 13e dalaï-lama. Selon Alastair Lamb, Gongkar succomba, encore jeune, à une pneumonie en 1917, privant l'armée tibétaine de l'expérience qu'il avait acquise[21] - [22]. Selon K. Dhondup, un historien tibétain, il est retourné au Tibet en et est mort de la malaria en à Lhassa[23].

R. D. Ringang

Né en 1904 et le plus jeune des quatre, Rinzin Dorji Ringang était resté plus longtemps en Angleterre et avait fait des études de génie électrique à l'université de Londres et à celle de Birmingham avant de rentrer au pays en 1924[24]. Il construisit, dans la vallée de Dodé, la première centrale hydroélectrique du Tibet à partir d'équipements acheminés depuis l’Angleterre et posa une ligne électrique jusqu'à la ville et au palais d'été du dalaï-lama, une entreprise colossale pour un Tibétain. Hormis pendant les mois d'hiver où la rivière gelait, la centrale fournissait de l'électricité à la ville. En 1935, il fonda également Drapchi Lekhung, une usine hydroélectrique située à Drapchi près de Lhassa, alimentée par la centrale[25]. Selon Robert W. Ford, après la mort de Ringang, la centrale de la vallée de Dodé ne fut plus entretenue faute d’argent[26] - [27]. Peter Aufschnaiter, un évadé autrichien arrivé à Lhassa le , fut chargé par le gouvernement tibétain d'évaluer si l'ancienne centrale électrique pouvait être agrandie[28]. À l'aide de Reginald Fox, qui en conçut les plans, Aufschnaiter construisit une centrale beaucoup plus performante que la précédente[29].

Bilan

Pour le fils de Lungshar, Lhalu Tsewang Dorje, qui s'en ouvrit à l'opérateur radio britannique Robert W. Ford, « l'expérience n'[avait] pas été un franc succès ». Pour ce dernier, la faute n’en incombait pas entièrement aux anciens élèves tibétains de Rugby[4]. Ringang est le seul qui eût réussi au Tibet, ayant construit une station hydroélectrique et établi une ligne électrique jusqu'à Lhassa et au Norbulingka[6]. Pour Alastair Lamb, les deux autres élèves, Möndö et Kyipup, furent aiguillés sur une voie de garage par le pouvoir tibétain[30].

Pour l'historien Peter Hopkirk, l'expérience fut une réussite partielle. Un fonctionnaire britannique déclara que ces enfants « étaient sortis du Tibet timides et frustes ; ils y revinrent parlant l'anglais à la perfection et faits aux usages du monde. »[5]

Pour Alastair Lamb, l'apport des « quatre Tibétains de Rugby » au développement du Tibet fut minime et leur expérience ne rendit pas les Tibétains plus anglophiles pour autant. Elle ne fut pas renouvelée pendant les ultimes décennies de la présence britannique dans le sous-continent indien[31]. L'une des raisons est que les parents ne souhaitaient pas envoyer leur enfant au loin, aussi, le gouvernement tibétain invita un éducateur britannique, Frank Ludlow, qui dirigea l'école anglaise de Gyantsé (1923 - 1926)[32] - [33].

Selon le 14e dalaï-lama, ils firent un excellent travail à leur retour. L'un d'eux (Ringang) mit en place un réseau électrique dans une partie de Lhassa, et un autre (Kyipup) une liaison télégraphique entre Gyantsé et Lhassa, raccordant ainsi Lhassa au réseau anglo-indien et au reste du monde[34]. Lungshar lui-même apprit beaucoup lors de son séjour. À son retour, il commença à moderniser l'armée tibétaine[3]. Il fut nommé ministre des finances après son retour en , puis commandant en chef de l'armée en 1925 ou 1929[35].

Alex McKay, pour sa part, fait remarquer qu'avec leurs compatriotes qui avaient fait des études en Inde britannique ou à l'école anglaise de Gyantsé de Frank Ludlow, ils formaient un cercle grandissant de penseurs progressistes (en règle générale) dont la fréquentation était agréable pour les visiteurs européens et qui étaient considérés comme un important relais des idées occidentales[36].

En 1946, lorsque l'Autrichien Heinrich Harrer, évadé du camp britannique de Dehradun en Inde, gagna Lhassa, il ne restait plus qu'un seul des anciens élèves de Rugby, à savoir Kyipup, à l'époque haut responsable du bureau des affaires étrangères. Évoquant ce dernier, Peter Fleming le qualifie de « seul survivant d'une expérience sensée mais que les Tibétains ne parvinrent jamais à renouveler »[37].

Notes et références

- Ils sont désignés dans divers ouvrages sous les appellations de the four Rugby boys, the four young Tibetans, the four Tibetan youths, the four Tibetans in England, the Rugby party.

- (en) British Intelligence on China in Tibet, 1903-1950, Formerly classified and confidential British intelligence and policy files, Editor: A.J. Farrington, Former Deputy Director, OIOC, British Library, London, IDC Publishers, 2002, p. 2 : « A fascinating group of files offers minute detail in an attempt to turn four young Tibetans into a vangard of "modernisers" through the medium of an English public school education ».

- Thomas Laird, Dalaï-Lama, Christophe Mercier, Une histoire du Tibet : Conversations avec le Dalaï Lama, Plon, 2007, (ISBN 2259198910), p. 251, 264 : « Lungshar les a accompagnés, et lui aussi a appris beaucoup en Angleterre. », « Lungshar était un fonctionnaire laïque qui avait conduit en Angleterre les quatre étudiants, et était revenu avec eux. À leur retour, ces quatre garçons ont très bien réussi. L'un a installé l’électricité dans une partie de Lhassa, et l'autre un télégraphe. Puis Lungshar, après son retour, a commencé la modernisation de l'armée, essayé de créer une armée moderne »

- (en) Robert W. Ford, Wind Between the Worlds, David McKay Company, Inc, New York, 1957, pp. 107-110, p. 109 (ce livre contient l'histoire des quatre élèves de Rugby telle que l'avait racontée à Robert Ford Lhalu Tsewang Dorje, le fils de Lungshar) : « "The experiment was not a great success," said Lhalu. That was not entirely the boys'faults. », (fr) Tibet rouge: capturé par l'armée chinoise au Kham, p. 99

- Peter Hopkirk (trad. de l'anglais par Christine Corniot), Sur le toit du monde : Hors-la-loi et aventuriers au Tibet, Arles, Philippe Picquier, , 279 p. (ISBN 2-87730-204-0), p. 217

- (fr) Robert W. Ford, op cit., p. 100.

- (en) Alastair Lamb, The McMahon line: a study in the relations between India, China and Tibet, 1904-1914, Volume 2, Routledge & K. Paul, 1966, repris sous le titre Tom Browns from Central Asia, in The History of Tibet: The modern period : 1895-1959, the encounter with modernity, ss la dir. de Alex Mackay, Routledge, 2003, 737 p., pp. 325-328, p. 327 : « The experiment of the education of the four Tibetan boys can hardly be described as a success. The boys made no significant contribution in later life to the development of Tibet, [...]. The experiment was not repeated during the remaining period of British rule in the Indian subcontinent. »

- Alastair Lamb, op. cit., p. 325 : « the Dalai Lama in August 1912 proposed that 'some energetic and clever sons of respectable families' in Tibet be sent to England. [...] At this time Basil Gould was about to go to England on leave. The Indian government, therefore, decided that he should guide the four Tibetans through the difficult first few weeks of their journry away from the roof of the world'. »

- Alastair Lamb, op. cit., p. 325 : « The boys were also to be accompanied on their trip by Lungshar and his wife and by the Sikkimese policeman Laden La, whose son, Sonam Topge, was also going to the United Kingdom for his schooling. »

- Alastair Lamb, op. cit., pp. 326 : « From the outset the British found Lungshar something of a nuisance. In theory no more than the official escort for the boys, in fact Lungshar regarded himself [...] as a Tibetan embassador at large. »

- Patrick French, Tibet, Tibet, une histoire personnelle d'un pays perdu, traduit de l'anglais par William Oliver Desmond, Albin Michel, 2005, (ISBN 978-2-226-15964-9), p. 192.

- (en) Tibet Album, British photography in Central Tibet 1920-1950, Mondo Biography.

- Alastair Lamb, op. cit., pp. 326 : « his wife undertook, with considerable success, the seduction of one of the Tibetan boys. »

- Michael Harris Goodman, Le Dernier Dalaï-Lama ?, p. 127

- Alastair Lamb, op. cit., pp. 326-327 : « The Tibetan boys settled down at The Warren Heath, Farnham, where they began to learn English under the supervision of the Berlitz School of Languages, while their future movements were being considered [...]. Gould records that, after a discussion between Sir A. Hirtzl, J. E. Shuckburgh and Gould, Harrow, Eton and Wellington were rejected and Rugby decided upon as just the place to educate Tibetans.10 This story is not entirely borne out by the archives, which suggest that the first school considered was Cheltenham.11 This was rejected only when it was discovered that three sons of President Yuan Shih-k'ai and a son of the Chinese Minister in London were also down for this establishment. The India Office asked the Foreign Office whether the headmaster of Cheltenham might be persuaded to refuse the Chinese boys; but the Foreign Office opinion that Yuan's sons were certainly a more prestigious addition to the school enrolment than four Tibetans ended this official attempt to meddle in public school politics. Rugby was then decided upon. »

- (en) Martin Brauen, Patrick A. McCormick, Shane Suvikapakornkul, Edwin Zehner, Janice Becker, The Dalai Lamas: a visual history, Serindia Publications, 2005, (ISBN 1932476229 et 9781932476224), p. 147 : « Kyibu, who had studied telegraphy, established a telegraph line from Lhasa to Gyantse, thus enabling Tibet to communicate with the outside world. »

- Robert W. Ford, op. cit., p. 108 : « He failed with the telegraph, and was then appointed City Magistrate and Chief of Police. [...] Then he went into the Foreign Office, and acted as interpreter and guide for English-speaking visitors. He also sometimes read the news in Tibetan on Radio Lhasa, and he was the speaker. »

- Robert Ford, op. cit., p. 108 : « One of them, a monk named Möndö, had [...] showed some aptitude for mining engineering, which he studied after leaving school. [...] Möndö came back and began prospecting. At once the local abbot protested that he was upsetting the spirits and would cause the crops to fail. Möndö did not want to be blamed for a possible bad harvest, so he moved to another district and began digging there. The same thing happened. After a few more attempts he abandoned prospecting [...]. »

- (en) Tsepon W. D. Shakabpa, Tibet: A Political History, Yale University Press, 1967, 369 p., p. 249 : « Khenrab Kunzang Mondrog majored in mining engineering, but on his return to Tibet he did not have the opportunity to put his specialty in practice. Instead, he became the Dalai Lama's interpreter and also served as superintendent of the Lhassa police. »

- Robert W. Ford, op. cit., p. 109 : « Ghonkar had gone to Woolwich, and was expected to remodel the Tibetan army. But for political reasons he had been posted to a frontier station in Kham, and he died young. »

- Alastair Lamb, op. cit., pp. 327-328 : « Gongkar went on to a short period of officer training with the Indian army, but his death of pneumonia in 1917 deprived the Tibetan armed forces of the benefit of his experience. [...] Gongkar is said to have fallen in love and tried to marry an English girl, but to have been refused permission for such a match by the Dalai Lama. »

- Robert W. Ford, op. cit., p. 109 : « I had heard a rumor that he had fallen in love with an English girl and been forbidden to marry her by the dalai Lama, and that he had died of a broken heart or somme other more sinister cause. »

- (en) K. Dhondup, The Thirteenth Dalai Lama's Experiment in Modern Education. The Tibet Journal, 1984, 9(3): 38-58. p. 46 : « Gongkar returned to Tibet by the middle of March 1919. A telegram dated 17.12.1919 from the Political Officer Sikkim to Secretary Foreign & Political Department, Government of India, reads: "Tibetan trade agent at Gyantse reported that Mr. Gongkar died at Lhasa from malaria about a month ago. »

- Alaister Lamb, op. cit., p. 327 : « Richengang, the youngest of the four boys, after Rugby was sent to the Universities of London and Birmingham. »

- (en) Tibet Album, British photography in Central Tibet 1920-1950, Ringang Biography

- (en) Robert W. Ford, op. cit., pp. 109-110 : « Ringang was the only one who achieved anything in Tibet. [...]. When he came back to Lhasa he built a hydroelectric power station at the foot of a mountain stream and laid a power line to the city and to the Dalai Lama's summer Palace. [...] It was a tremendous undertaking for a Tibetan — and it worked. Except for a few months in the winter, when the stream was frozen, it provided the city with electric light. But nothing was spent on maintenance, and after Ringang died the plant fell into disrepair. When I was in Lhasa it produced only enough power to drive the machines in the Mint. »

- (en) brève description physique et photographies, Tibet Album, British photography in Central Tibet 1920-1950.

- (en) Peter Aufschnaiter et Martin Brauen, Peter Aufschnaiter's eight years in Tibet, 2002, p. 90 : « The Tibetan government commissioned me to find out whether the old power station on the Doti River could be expanded. »

- Robert W. Ford, op. cit., p. 110 : « It was to replace this that Reginald Fox and Peter Aufschnaiter were building a new hydroelectric station on much more ambitions lines. »

- Alastair Lamb, op. cit., p. 327 : The other boys all returned to Tibet, where they were effectively sidetracked by the Tibetan establishment.

- Alastair Lamb, op. cit., p. 327 : « The boys made no significant contribution in later life to the development of Tibet, and they certainly made the Tibetan no more pro-British than would have been the case had they remained at home. The experiment was not repeated during the remaining period of British rule in the Indian subcontinent. »

- (en) Catriona Bass, Education in Tibet: policy and practice since 1950, Zed Books, 1998, (ISBN 1856496740 et 9781856496742), p. 2.

- Sam van Schaik, Tibet: A History, 2011, p. 203 : « In 1924, the Dalai Lama had extended his experiment of sending Tibetan boys to English schools by setting up a modern school based on British methods at Gyantse. »

- Roland Barraux Histoire des Dalaï-Lamas - Quatorze reflets sur le Lac des Visions, Albin Michel, 1993; réédité en 2002, Albin Michel (ISBN 2226133178), p. 291.

- (en) Alex McKay, The History of Tibet: The modern period : 1895-1959, the encounter with modernity, Routledge, 2003, (ISBN 0415308445 et 9780415308441), p. 521.

- (en) Alex McKay, [https://books.google.fr/books?id=mMP7HTbD-BEC&pg=PA136 Tibet and the British Raj: the frontier cadre, 1904-1947, Curzon Press, Richmond, 1997, 293 p., p. 136 : « They formed a growing circle of generally progressive thinkers, in whose company European visitors felt comfortable. [...] the cadre [...] recognised that 'the pupils from these schools ... constitute a major propaganda channel'. »

- (en) Heinrich Harrer, Seven Years in Tibet, translated from the German by Richard Graves; with an introduction by Peter Fleming; foreword by the Dalai Lama, E. P. Dutton, 1954. Introduction, p. X : « the only survivor of a sensible experiment that the Tibetans never got around to repeating ».