École anglaise de Gyantsé

L'école anglaise de Gyantsé est une école laïque moderne, basée sur le modèle de l'école privée anglaise et située dans la ville de Gyantsé au Tibet. Un éducateur britannique, Frank Ludlow, invité par le gouvernement tibétain, en fut le directeur. L'école, fondée par le 13e dalaï-lama, est ouverte en 1923. Elle est fermée trois ans plus tard en 1926[1].

| Fondation | |

|---|---|

| Dissolution | |

| Type | École |

| Directeur | Frank Ludlow |

|---|

| Pays |

|

|---|

| Coordonnées | 28° 57′ 00″ nord, 89° 38′ 00″ est | |

|---|---|---|

| Géolocalisation sur la carte : région autonome du Tibet

| ||

Histoire

Le projet

C'est lors de la Convention de Simla (en 1913) que l'idée de fonder une école britannique au Tibet fut évoquée par le plénipotentiaire tibétain, le premier ministre Paljor Dorje Shatra. Pour faire face aux pressions de la civilisation occidentale, elle semblait indispensable au gouvernement tibétain qui voyait que, sans éducation scolaire générale, on ne pouvait former de Tibétains pour développer le pays selon ses vœux[2]. Un responsable britannique insista pour préciser que l'école serait entièrement fondée par les Tibétains de leur propre initiative et que ce n'était en aucun cas une entreprise britannique augurant une « pénétration pacifique »[3].

Gyantsé est choisie car la ville possède déjà un agent commercial (David Macdonald) et une petite garnison militaire britanniques, formant une communauté susceptible de donner l’occasion aux élèves de fréquenter des Anglais[4]. Le nombre d’élèves serait au début entre 25 et 30 et aucun d’entre eux ne devrait avoir fait des études même en tibétain. Leur scolarité durerait de 5 à 8 ans selon les besoins puis ils seraient envoyés dans des écoles soit en Europe, soit à Darjeeling, Mussoorie, etc., en Inde pendant un an pour se frotter à de jeunes Européens et apprendre à connaître les coutumes, idées et mœurs européennes[5].

Ouverture et enseignements

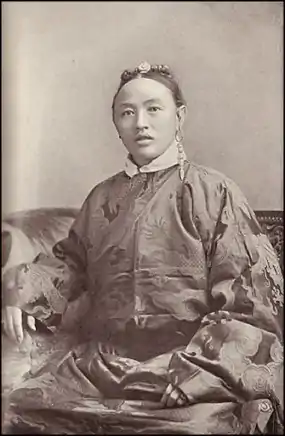

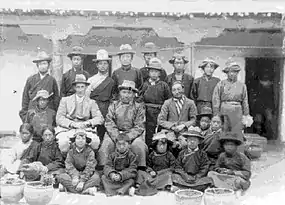

En 1923, le 13e dalaï-lama fonde l'école anglaise de Gyantse sous la direction de Frank Ludlow[6]. L'école ouvre le avec 30 élèves, des garçons âgés de 8 à 18 ans dont aucun ne venait de Lhassa, ni n'était le fils d'un responsable du gouvernement. Certains étaient bien habillés, tandis que d'autres avaient une origine modeste de toute évidence[7]. Ils sont choisis par le Bureau des Finances parmi les familles de l'aristocratie laïque[8]. Les conversations en anglais étaient la priorité, et Ludlow était fier au terme des trois ans de son mandat que la plupart des enfants de sa classe pouvaient tenir une conversation sensée sur tout sujet. Il ajouta ensuite la géographie au programme[9]. En 1926, les garçons plus avancés « faisaient d'excellents progrès en anglais. Leur orthographe et écriture étaient excellentes, ils commençaient à parler couramment et s’intéressaient de près à des livres comme Robin des bois, Guillaume Tell, Les Chevaliers de la table ronde, etc. En arithmétique, ils avaient acquis une bonne compréhension des fractions et des nombres décimaux[10].

Fermeture

Le , la décision de fermeture de l'école est transmise à Ludlow par Frederick Williamson (en), qui lui enverra la copie d'une lettre où le Kashag explique ses raisons. Les parents, déclare le Kashag, « se sont continuellement plaints qu'à moins que leurs garçons n'apprennent leur propre langue à fond au départ, ils ne peuvent pas travailler au service du gouvernement tibétain de façon satisfaisante ». Ils ont réitéré la proposition que des professeurs indiens viennent chez eux enseigner l'anglais, mais ont insisté pour affirmer qu'ils avaient le plus grand respect pour Ludlow [11].

Avis de Ludlow

Ludlow n'a pas imputé la fermeture de l'école qu'aux Tibétains, il pensait aussi que les autorités britanniques en Inde étaient tout aussi coupables. Frederick Markham Bailey pensait aussi que le Foreign Office aurait pu donner beaucoup plus d'encouragements[12]. L'école ferma en , date du départ de Ludlow du Tibet[13].

Avis de David Macdonald

En dehors des raisons officielles invoquées par le gouvernement tibétain pour abandonner le projet, David Macdonald en identifie trois supplémentaires : (i) les parents s'opposaient à l'envoi de leurs enfants si loin de chez eux ; (ii) les lamas y étaient opposés car selon eux, si les enfants devaient apprendre pour moitié de leur temps l'anglais et pour l'autre le tibétain, ils n'apprendraient aucune des deux langues correctement ; et (iii) le gouvernement tibétain était dans l'incapacité de payer régulièrement le salaire du maître d'école[14].

Autres avis

Pour Yangdon Dhondup, l’échec de ce projet est liée aux factions conservatrices du clergé[15]. Pour Robert W. Ford, c'est en raison d'un changement dans la politique extérieure du Tibet, qui amorçait une coopération avec la Chine, que l'école fut fermée[16].

Pour Alex McKay, l'école anglaise dut fermer en raison d'un mouvement tibétain général opposé à la modernisation à cette époque[17].

Pour Jérôme Edou et René Vernadet, c'est l'opposition des grands monastères qui contraignit l'école à fermer[18].

Influence

Pour Alastair Lamb (en), l'école anglaise fut un échec dans la mesure où elle était censée accroître l'influence britannique au Tibet grâce aux élèves appelés à devenir, du moins l'espérait-on, de puissants responsables du gouvernement tibétain. Selon lui, guère de responsables (sinon aucun) ayant été à l'école anglaise ne semblent avoir exercé une influence importante dans les affaires du pays[19]. Pour d'autres auteurs, Ludlow eut une influence considérable, et en 1942 de nombreux hauts responsables tibétains avaient été ses élèves à Gyantsé[20].

Anciens élèves

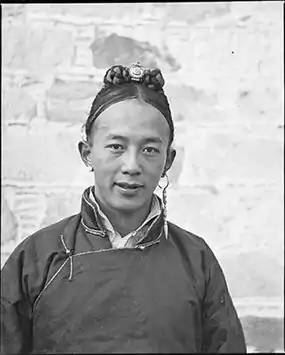

Au nombre des anciens élèves célèbres de l'école, figurent :

- Surkhang Lhawang Topgyal[21], homme politique, militaire et diplomate tibétain.

- Kelsang Wangdu (Dergé Sé)[22], qui devint le gouverneur de Markham Gartok[23].

- Horkhang Sé (Horkhang Sonam Palbar), qui devint ministre laïc des Finances[24].

- Doring Thaiji[25] Tenzin Norbu (1900- mort après 1959), nommé dzongpön de Nyalam en 1932, il fut promu au 4e grade en 1934, et on lui confia la mission délicate de rencontrer le 9e panchen-lama, exilé en Chine à l'époque. De retour en 1938, il fut nommé contrôleur des biens du 13e dalaï-lama[26].

- Doring Se (Dadul Wangyal), devenu responsable tibétain le , il fut nommé assistant du ministre Lhalu Shape en [27].

- Tendong Dzongpon (Palden Gyaltsen) était chargé des propriétés du gouvernement tibétain à Chayul avant de devenir assistant à l'usine hydro-électrique de Drapchi près de Lhassa. Il fut nommé dzongpön de Gyantsé en 1935, et de Trachhen Dzong dans le Kham en 1942. Il fut nommé assistant télégraphe à Lhassa en [28].

- Dhondup Khangsar II (Sonam Wangchhuk) entra au service du gouvernement en 1939, nommé clerc du Kashag en , dzongpön de Chomo Dzong dans le Kongpo en 1942. Devenu rupön du régiment des Kusung, il fut posté dans le district de Naktshang en [29].

- Lhagyari Kelzang Nyendrak (début du XXe - 1952), père de Lhagyari Namgyal Gyatso[30]

Projet de réouverture

Les autorités tibétaines souhaitaient rouvrir l'école. L'agent commercial de Gyantsé rapporte en 1932 qu'il avait été décidé d'ouvrir une école anglaise à Lhassa, les murs avaient été élevés et le gouvernement souhaitait réengager Frank Ludlow. Ce projet ne se concrétisa pas, mais il ne disparut pas totalement. Ainsi, Ludlow écrit en 1937 qu'il avait appris l'année précédente que le gouvernement envisageait de rouvrir l'école de Gyantsé. Il ajoute qu'il est maintenant trop âgé pour rester longtemps à une telle altitude mais espère qu'une personne plus jeune comme Spencer Chapman pourra accepter[31].

Références

- (en) Catriona Bass, Education in Tibet: policy and practice since 1950, Zed Books, 1998, (ISBN 1856496740 et 9781856496742), p. 2.

- (en) Michael Rank, King Arthur comes to Tibet: Frank Ludlow and the English school in Gyantse, 1923-26, Institut de tibétologie Namgyal, 2004, « At the Simla Convention, the idea of setting up a British-run school in Tibet also came up. Sir Charles Bell, doyen of British policy in Tibet, noted that it was the Tibetan Plenipotentiary who broached the subject: “Something of the kind seems indispensable to enable the Tibetan Government to meet the pressure of Western civilization. And they themselves are keen on it. Without such a general school education Tibetans cannot be trained to develop their country in accordance with their own wishes.” »

- Michael Rank, op. cit., « another Government of India official stressed that it should be “made clear that the school is being established by the Tibetans on their own initiative and will be entirely their own affair i.e. it is not in any way a British enterprise betokening ‘peaceful penetration'. »

- Michael Rank, op. cit., p. 50 : « it was eventually decided to open an ‘English school’ at Gyantse, […] where there was already a British trade agent and military escort. The presence of a British community there “offers the opportunity to the students of mixing with a few people of British race.” »

- Michael Rank, op. cit., p. 50 : « “The number of students likely to attend the school at the beginning will be between 25 and 30, none of whom will presumably have had any previous education even in Tibetan. It is proposed to give the boys sound education in both English and Tibetan for 5, 6, 7 or 8 years according to their requirements and send them thereafter to European schools at hill stations, such as Darjeeling, Mussoorie, Naini Tal, etc., for about a year in order for them to mingle with European boys and to learn European ideas, manners and customs.” »

- Melvyn C. Goldstein, A History of Modern Tibet, 1913-1951, p. 421 : « in 1923 he opened an English school in Gyantse under the tutelage of Frank Ludlow, an Englishman ».

- Michael Rank, op. cit., « 30 boys had arrived, aged 8 to 18, though none of them was from Lhasa or hence the son of a Lhasa government official. “Some of them were charming kiddies, well-bred and wellclothed. Others were not so prepossessing and evidently came of more plebeian stock. [...]” (8 November, 1923). »

- Melvyn C. Goldstein, A History of Modern Tibet, 1913-1951: The Demise of the Lamaist State, p. 423

- Michael Rank, op. cit., « English conversation was a top priority, and Ludlow was proud to report that by the end of three years “most of the boys in my class were able to carry on an intelligible conversation on any ordinary topic.” Once his pupils understood enough English, he added geography to the curriculum. »

- Michael Rank, op. cit. : « By 1926, [...] the more advanced boys were “making excellent progress in English. Their spelling and handwriting were excellent, they were beginning to talk with commendable fluency, and were deeply interested in such books as Robin Hood, William Tell, King Arthur’s Knights, etc. In arithmetic they had obtained a good grasp of fractions, decimals [...]” ».

- Michael Rank, op. cit. : « “I got a wire from Williamson to-day definitely stating that the school was to be closed. [...] (20 August, 1926). Williamson sent Ludlow a copy of a letter from the Kashag explaining their reasons for closing the school. The parents, the Kashag stated, “have been continually complaining that unless their boys have learnt their own language thoroughly in the beginning, the boys cannot do the Tibetan Govt service satisfactorily for the present & in future.” They reiterated the proposal that the boys be taught English by Indian babus in their own homes, but stressed they had nothing but the greatest respect for Ludlow. »

- Michael Rank, op. cit. : « Ludlow did not blame the Tibetans entirely for the closure of the school, however, and felt that the British authorities in India were just as culpable. [...] Bailey agreed that the Foreign Office could have offered much more encouragement. He told Ludlow that “if the Foreign Office were to encourage him to go to Lhasa more often something might be done, & also if [sic] a little personal advice & support of Tibet at the present time might save a great deal of trouble later on. I quite agree. [...] »

- Michael Rank, op. cit. : « Ludlow was by now booked to return home on the P&O liner the Ranchi, leaving Bombay on 20 November. The very thought made him miserable. “I hate going down hill. It means India & the plains & heat & I loathe India & the plains & the heat after Tibet,” he wrote on his trek near Yatung (7 November, 1926). »

- (en) H. Louis Fader, Called from obscurity: the life and times of a true son of Tibet, God's humble servant from Poo, Gergan Dorje Tharchin: with particular attention given to his good friend and illustrious co-laborer in the Gospel Sadhu Sundar Singh of India, Volume 2, Tibet Mirror Press, 2004 (ISBN 9993392200 et 9789993392200), p. 117 : « Apart from other, more official reasons put forward by the Tibetan government for abandoning the project, Macdonald identified the following additional explanations for the school's early demise: (i) the parents were opposed to sending their sons so far away from home; (ii) the lamas were against the school because they reasoned that if there was a division in the use of the boys' time between English and Tibetan they would not learn either language properly; and (iii) the Tibetan government was unable to maintain regular payment of the Headmaster's salary. »

- (en) Yangdon Dhondup, Roar of the Snow Lion: Tibetan Poetry in Chinese, in Lauran R. Hartley, Patricia Schiaffini-Vedani, Modern Tibetan literature and social change, Duke University Press, 2008, 382 p., (ISBN 0822342774 et 9780822342779), p. 37 : « There were a number of attempts to establish other schools such as the Gyantsé school and the Lhasa English school but unfortunately these projects were undermined by conservative factions within the clergy. »

- Robert W. Ford, Tibet Rouge, Capturé par l’armée chinoise au Kham, Olizane, 1999 (ISBN 2-88086-241-8) p. 72.

- (en) Alex McKay, “The Birth of a Clinic”? The IMS Dispensary in Gyantse (Tibet), 1904–1910 : « An English school existed in Gyantse in the period 1923–26; it was closed as part of a general Tibetan movement against modernization at that time. »

- Jérôme Edou et René Vernadet, Tibet, les chevaux du vent : une introduction à la culture tibétaine, Paris, L'Asiathèque, , 462 p. (ISBN 978-2-915255-48-5), p. 76-77 : « Durant les quelques années qui suivirent la Convention de Simla, le dalaï-lama tenta de développer un rapprochement avec les Anglais [...]. Une école anglaise fut créée à Gyantsé mais, devant la réaction des grands monastères [...], l'école dut rapidement fermer ses portes. »

- Michael Rank, op. cit., p. 50 : « The main purpose of the school was to increase British influence in Tibet through the students, who, it was hoped, would eventually become powerful officials in the Tibertan government. To this extent, the school was a failure and few if any of Ludlow's officials seem to have exerted a significant degree of influence in their country's affairs [...] 30 The McMahon Line by Alastair Lamb (London, 1966), p. 603. »

- (en) Richard Starks, Miriam Murcutt, Lost in Tibet: The Untold Story of Five American Airmen, a Doomed Plane, and the Will to Survive, Globe Pequot, 2005, (ISBN 1592287859 et 9781592287857) p. 90 : « Ludlow wielded considerable influence; many of Tibet's more senior officials were former pupils of his, having attended the English school Ludlow had set up in Gyantse nearly twenty years before. »

- Surkhang Lhawang Topgyal

- (en) Derge Se Kusho

- Robert W. Ford, Tibet Rouge, p. 72

- Robert W. Ford, Tibet Rouge, p. 73.

- (en) H. Louis Fader, op. cit., p. 117 : « Doring Thaiji, [...] had the opportunity of attending the Ludlow school ».

- (en) Luciano Petech, Aristocracy and government in Tibet, 1728-1959, 1973, p. 64 : « rDo-rih bsTan-'dzin-nor-bu (b. 1900), [...]. In 1932 he was appointed g5Ja'-lam rdzon-dpon and in 1934 he was promoted to the 4th rank and was entrusted with a delicate mission to the Pan-c'en, then living in exile on the Chinese border (HR) 1. He returned in 1938 and was appointed supervisor of the property of the late Dalai-Lama. [...] He died after 1959 at Gyantse. The name of this family, one of the most noble in Tibet, was kept alive by the marriage of dGra-'dul-dbah-rgyal (bc 1913), of the sMon-'ts'o-ba family, to bsTan-'dzin-nor-bu's only sister. He had attended Frank Ludlow's school at Gyantse. About 1944 he was sent to be trained in wireless work at the British mission at Lhasa. »

- (en) Doring Se.

- (en) Tendong Dzongpon.

- (en) Dhondup Khangsar II.

- https://treasuryoflives.org/biographies/view/Kelzang-Nyendrak/TBRC_P8LS4349

- (en) Michael Rank, op. cit., p. 74 : « There were occasional reports that the Tibetan authorities wished to reopen the school. The Trade Agent at Gyantse reported in 1932 that “It has been decided to start an English School in Lhasa and the building has already been erected. The Tibetan Government are anxious to obtain the services of Mr. F. Ludlow who was in charge of the school at Gyantse, as head”32. Nothing became of this plan, but it did not completely evaporate. Ludlow wrote in 1937 that “I learnt last year that the Tibetan Govt meditated re-opening the Gyantse School. I am afraid the job has no attractions for me now (even if I was wanted). They ought to have a younger man - [Spencer] Chapman for instance if he would take it. I’m too old to live at 13,000’ for any prolonged period...” (letter to Bailey, 29 August, 1937). »