Légation chinoise à Lhassa

La Légation chinoise à Lhassa[3] - [4], ou Mission chinoise à Lhassa, ouverte en 1934 et fermée en 1949, était devenue peu à peu, selon Hugh Richardson, une véritable mission diplomatique[5] de la République de Chine au Tibet.

| Mission chinoise à Lhassa | ||

République de Chine (1912-1949) |

||

|---|---|---|

Un lion de pierre devant l'ancienne résidence chinoise, 1939[2] | ||

| Lieu | Lhassa | |

| Coordonnées | 29° 39′ nord, 91° 06′ est | |

| Nomination | 1934 | |

| Géolocalisation sur la carte : région autonome du Tibet

| ||

| Voir aussi : Bureau du Tibet | ||

Histoire

La mission chinoise de « condoléances » envoyée par le gouvernement de la République de Chine et dirigée par le général Huang Musong et les quatre-vingts personnes de son escorte arrive à Lhassa le [6] avec l'autorisation du gouvernement tibétain[7], après le décès du 13e dalaï-lama.

Après le retour en Chine de Huang Musong, elle laissa derrière elle deux agents de liaison munis d'un émetteur-récepteur radio[8]. L'installation par des responsables chinois d'une station de radio permanente à Lhassa fut autorisée par le régent du Tibet, Réting Rinpoché, et la mission chinoise, composée de Jiang Zhiyu et de Liu Puchen, commença à se constituer[9].

En 1939, Chang Wei-pei, technicien radio de la légation et alors représentant par intérim de la République de Chine, salua à l'extérieur de Lhassa Ernst Schäfer, chef de l'expédition allemande au Tibet (1938-1939)[10] - [11]. La légation chinoise permit à Ernst Schäfer d'utiliser la radio de la légation[3].

Le [12], le représentant de la République de Chine, les membres de la mission et tous les Chinois furent expulsés du Tibet. Si la raison officielle était que la mission n'avait plus de rapports avec le gouvernement nationaliste chinois et qu'elle ne pouvait être accréditée par le nouveau gouvernement communiste, la raison véritable était le gouvernement tibétain craignait qu'une partie, voire la totalité des membres de la mission ne se rallient au nouveau gouvernement [13].

Représentants de la République de Chine

Entre 1934 et 1949, se succédèrent à Lhassa les représentants suivants de la République de Chine[14] :

- Liu Puchen : - (jusqu'à son décès à Lhassa) ;

- Chiang Chu-yi (Jiang Zhiyu) : - (quitta son poste en pour rejoindre la Chine via l'Inde)[15] ;

- Gao Changhzu : (retenu à la frontière sino-tibétaine et ne fut jamais en mesure d'atteindre Lhassa) ;

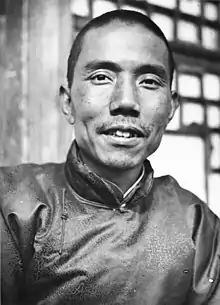

- Chang Wei-pei (Zhang Weibai, Zhang Ziyi, Tang Fe-tang): - (technicien radio de la légation, officia durant la vacance en tant que représentant ad interim) ;

- Kong Qingzong: - ;

- Shen Tsung-lien (Shen Zonglian): - ;

- Chen Xizhang : - (représentant ad interim de jusqu'à son expulsion en ).

Notes et références

- « Lhasa, die Steinlöwen und Landschaft des alten chinesischen Jamens »

- « Lhasa, die Steinlöwen und Landschaft des alten chinesischen Jamens »

- (en) John J. Reilly, Compte rendu du livre de Christopher Hale, Himmler's Crusade. The Nazi Expedition to Find the Origins of the Origins of the Aryan Race : « Not that mail was Schäfer’s only means of communication: the Chinese legation let him use their radio ».

- (en) Heinrich Harrer, Seven years in Tibet : « Soon we had collected quite a number of players. Incontestably the best was Mr. Liu, the secretary of the Chinese Legation »

- (en) Hugh Richardson, A short history of Tibet, 1962, p. 143 : « General Huang's mission was successful in making the first breach in the exclusion of Chinese officials from Tibet which had lasted for twenty years. He contrived to leave behind him two liaison officers with a wireless set and that foothold gradually turned into a regular diplomatic mission. »

- Roland Barraux, Histoire des Dalaï-Lamas - Quatorze reflets sur le Lac des Visions, préface de Dagpo Rinpotché, Albin Michel, 1993 ; réédité en 2002, Albin Michel (ISBN 2226133178), p. 307.

- (en) Robert Barnett, Lhasa: Streets with Memories, Columbia University Press, 2006, (ISBN 9780231136808), p. 21.

- (en) Heather Spence, British Policy and the 'development' of Tibet 1912-1933, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, Department of History and Politics, Faculty of Arts, University of Wollingong [Australia], 1993, x + 362 p. : « The Nanking government saw in the Thirteenth Dalai Lama's death the opportunity to send a 'condolence' mission to Lhasa. When the mission returned to China, two liaison officers with a wireless transmitter remained at Lhasa. In a counter-move, a rival British Mission was quickly established by Hugh Richardson ».

- Thomas Laird, avec le Dalaï-Lama, Christophe Mercier, Une histoire du Tibet : Conversations avec le Dalaï Lama, Plon, 2007, (ISBN 2259198910), p. 293.

- (en) Hsiao-Ting Lin, Tibet And Nationalist China's Frontier: Intrigues And Ethnopolitics, 1928-49, p. 82 : « List of Nationalist Chinese Representatives at Lhasa. [...] Technician of the Chinese wireless station in Lhassa. Served as acting representative. »

- (en) Christopher Hale, Himmler's Crusade. The Nazi Expedition to Find the Origins of the Aryan Race, p. 150 « Huang did not go away empty-handed. Since he could claim that his mission had led to 'dialogue', he persuaded the Tibetans to allow some of his colleagues to remain in Lhasa with their wireless. One of them would greet the humiliated Ernst Schäfer outside Lhasa five years later. His name was Chang Wei-pei, and he was said to be something of an oddball and an opium addict. »

- Roland Barraux, op. cit., p. 323.

- Claude Arpi, Tibet, le pays sacrifié, Bouquineo, 2011, 388 p., p. 252.

- (en) Hsiao-Ting Lin, Tibet And Nationalist China's Frontier: Intrigues And Ethnopolitics, 1928-49, p. 82

- (en) Alastair Lamb, Tibet, China & India, 1914-1950: a history of imperial diplomacy, 1989, p. 282 : « Meanwhile Chiang Chu-yi had defied his instructions and left Lhasa for India and China via Sikkim in late November 1937. The Chinese, well aware that they were unlikely to slip in a new representative through India without, at least, reopening discussions on Tibet with the British Embassy in Peking, decided to confirm the Chinese wireless operator in Lhasa, Chang Wei-pei (in some British sources referred to as Tang Fe-tang), as head of the Chinese Mission and Chiang's successor. Chang was said to smoke opium and be rather eccentric in behaviour. »