Chenopodium

Chenopodium, les Chénopodes, sont un genre de plantes dicotylédones, annuelles, herbacées, très odorantes de la famille des Amaranthaceae ou, des Chenopodiaceae, en fonction de la classification retenue. Les chénopodes sont largement répandu dans le monde entier, principalement en zone tempérée et subtropicale[2]. L'Europe en compte plusieurs dizaines d'espèces (trente, rien qu'en Pologne)[3].

C'est un exemple de plante hémérochore en provenance d'Australie, plutôt qu'ayant transité d'Europe vers l’Australie.

Étymologie

Le genre doit son nom à la ressemblance des feuilles avec la trace d'une patte d'oie (du latin scientifique chenopodium, formé à partir des mots grecs χήν,-νός, chéinos [oie] et πόδῖον, podios [petit pied], littéralement patte-d'oie)[4].

Usages

Diverses espèces de chénopodes sont cultivées et mangées, et/ou ont été utilisées par les médecines traditionnelles. On sait qu'ils sont riches en flavonoides (glucosides de type kaempférol et quercétine), en acides phénoliques et en terpénoïdes[5] - [6]. Leurs feuilles sont riches en caroténoïdes et leurs graines sont riches en protéines et lipides[7].

Plusieurs propriétés médicinales ont été confirmées en laboratoire et d'autres récemment découvertes ou à l'étude (activités antiprurit, antibactérienne, antifongiques et anticancer…)[7] - [8] - [9] - [10] - [11].

Classification

Ce genre a été décrit par le naturaliste suédois Carl von Linné (1707-1778).

Dans la classification de Cronquist il est classé dans la famille des Chenopodiaceae, tandis que dans la classification APG III, il fait partie des Amaranthaceae.

Liste d'espèces

Selon GRIN (27 septembre 2015)[12] :

Notez que le Chénopode bon-Henri, espèce bien connue des francophones, auparavant nommé Chenopodium bonus-henricus L. est considéré par GRIN comme synonyme de Blitum bonus-henricus[13].

- Chenopodium acuminatum Willd.

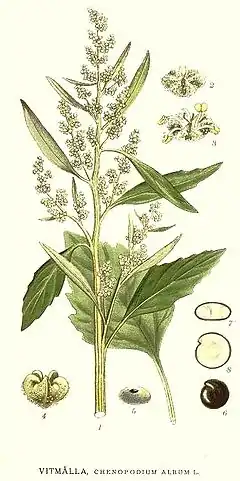

- Chenopodium album L. - Chénopode blanc

- Chenopodium atrovirens Rydb.

- Chenopodium baccatum Labill.

- Chenopodium berlandieri Moq.

- Chenopodium bolivianum Murr

- Chenopodium carnosulum Moq.

- Chenopodium desiccatum A. Nelson

- Chenopodium ficifolium Sm.

- Chenopodium formosanum Koidz.

- Chenopodium fremontii S. Watson

- Chenopodium gaudichaudianum (Moq.) Paul G. Wilson

- Chenopodium giganteum D. Don

- Chenopodium hastatum Phil.

- Chenopodium hians Standl.

- Chenopodium hircinum Schrad.

- Chenopodium hybr.

- Chenopodium incanum (S. Watson) A. Heller

- Chenopodium leptophyllum (Moq.) Nutt. ex S. Watson

- Chenopodium neomexicanum Standl.

- Chenopodium nevadense

- Chenopodium nutans (R. Br.) S. Fuentes & Borsch

- Chenopodium oahuense (Meyen) Aellen

- Chenopodium opulifolium Schrad. ex W. D. J. Koch & Ziz

- Chenopodium pallescens Standl.

- Chenopodium pallidicaule Aellen

- Chenopodium parabolicum (R. Br.) S. Fuentes & Borsch

- Chenopodium petiolare Kunth

- Chenopodium philippianum Aellen

- Chenopodium pilcomayense Aellen

- Chenopodium pratericola Rydb.

- Chenopodium preissii (Moq.) Diels

- Chenopodium purpurascens B. Juss. ex Jacq.

- Chenopodium querciforme Murr

- Chenopodium quinoa Willd.

- Chenopodium spinescens (R. Br.) S. Fuentes & Borsch

- Chenopodium standleyanum Aellen

- Chenopodium strictum Roth

- Chenopodium vulvaria L.

- Chenopodium watsonii A. Nelson

Selon Tropicos (27 septembre 2015)[14] (Attention liste brute contenant possiblement des synonymes) :

- Chenopodium acerifolium Andrz.

- Chenopodium acicularis (Paul G. Wilson) S. Fuentes & Borsch

- Chenopodium acuminatum Willd.

- Chenopodium acutifolium Sm.

- Chenopodium adpressifolium Pandeya & A.Pandeya

- Chenopodium aegyptiacum Hasselq.

- Chenopodium agreste E.H.L. Krause

- Chenopodium albescens Small

- Chenopodium album L.

- Chenopodium alexandrinum Desf. ex Moq.

- Chenopodium allanii Aellen

- Chenopodium altissimum L.

- Chenopodium amaranticolor (H.J. Coste & A. Reyn.) H.J. Coste & A. Reyn.

- Chenopodium ambiguum R. Br.

- Chenopodium amboanum Aellen

- Chenopodium ambrosioides L.

- Chenopodium ameghinoi Speg.

- Chenopodium amurense Ignatov

- Chenopodium andicola (Phil.) Reiche

- Chenopodium angulatum Curtis ex Steud.

- Chenopodium angulosum Lam.

- Chenopodium angustatum All.

- Chenopodium angustifolium Gilib.

- Chenopodium anidiophyllum Aellen

- Chenopodium antarcticum (Hook. f.) Hook. f.

- Chenopodium anthelminticum L.

- Chenopodium arenarium G. Gaertn., B. Mey. & Scherb.

- Chenopodium aridum A. Nelson

- Chenopodium aristatum L.

- Chenopodium arizonicum Standl.

- Chenopodium astracanium Ledeb.

- Chenopodium astrachanicum Ledeb.

- Chenopodium atriplicifolium (Spreng.) A. Ludw. ex Asch. & Graebn.

- Chenopodium atripliciforme Murr

- Chenopodium atriplicinum (F. Muell.) F. Muell.

- Chenopodium atriplicis L. f.

- Chenopodium atrovirens Rydb.

- Chenopodium augustanum All.

- Chenopodium auricomiforme Murr & Thellung

- Chenopodium auricomum Lindl.

- Chenopodium australasicum Moq.

- Chenopodium australe R. Br.

- Chenopodium ayare Toro Torrico

- Chenopodium baccatum Labill.

- Chenopodium badachschanicum Tzvelev

- Chenopodium baryosmon Schult.

- Chenopodium baryosmum Roem. & Schult.

- Chenopodium benghalense Spielm. ex Steud.

- Chenopodium berlandieri Moq.

- Chenopodium bernburgense (Murr) Druce

- Chenopodium betaceum Andrz.

- Chenopodium bicolor Bojer ex Moq.

- Chenopodium biforme Nees

- Chenopodium bipinnatifidum Moric. ex Moq.

- Chenopodium bisaeriale Menyh.

- Chenopodium blackianum Aellen

- Chenopodium blitoides Lej.

- Chenopodium blitum F. Muell.

- Chenopodium blomianum Aellen

- Chenopodium bohemicum F. Dvořák

- Chenopodium bolivianum Murr

- Chenopodium bonariense (Hook. f.) Hassl.

- Chenopodium bonus-henricus L.

- Chenopodium borbasiforme Druce

- Chenopodium borbasii Murr

- Chenopodium borbasioides generic LUDWIG ex Asch. & Graebn.

- Chenopodium boscianum Moq.

- Chenopodium botrydium St.-Lag.

- Chenopodium botryodes Sm.

- Chenopodium botryoides Raf. ex Moq.

- Chenopodium botrys L.

- Chenopodium browneanum Roem. & Schult.

- Chenopodium bryoniifolium Bunge

- Chenopodium buchananii Kirk

- Chenopodium burkartii (Aellen) Vorosch.

- Chenopodium bushianum Aellen

- Chenopodium calceoliforme Hook.

- Chenopodium californicum (S. Watson) S. Watson

- Chenopodium camphoratifolium Pourr.

- Chenopodium camphorosmoides Moq.

- Chenopodium candicans Lam.

- Chenopodium candolleanum (Moq.) S. Fuentes & Borsch

- Chenopodium canihua Cook

- Chenopodium capillare M.E. Jones

- Chenopodium capitatum (L.) Ambrosi

- Chenopodium carinatum R. Br.

- Chenopodium carnosulum Moq.

- Chenopodium carthagenense Zucc.

- Chenopodium catenulatum Schleich. ex Steud.

- Chenopodium caudatum Jacq.

- Chenopodium ccoyto Toro Torrico

- Chenopodium ccuchi-huila Toro Torrico

- Chenopodium centrorubrum Nakai

- Chenopodium chaldoranicum Rahimin. & Ghaemm.

- Chenopodium chenopodioides (L.) Aellen

- Chenopodium chilense Schrad.

- Chenopodium chrysomelanospermum Zuccagni

- Chenopodium chrysomenalospermum Zuccani

- Chenopodium cinereum Moq.

- Chenopodium citriodorum Steud.

- Chenopodium clemente Spreng.

- Chenopodium cochlearifolium Aellen

- Chenopodium conardii A. Nelson

- Chenopodium concatenatum Thuil

- Chenopodium congestum Hook. f.

- Chenopodium congolanum (Hauman) Brenan

- Chenopodium cordobense Aellen

- Chenopodium cornutum (Torr.) Benth. & Hook. f. ex S. Watson

- Chenopodium coronopodum St.-Lag.

- Chenopodium coronopus Moq.

- Chenopodium covillei Aellen

- Chenopodium crassifolium Hornem.

- Chenopodium cristatum (F. Muell.) F. Muell.

- Chenopodium crusoeanum Skottsb.

- Chenopodium cuneifolium Vahl

- Chenopodium curvispicatum Paul G. Wilson

- Chenopodium cyanifolium Pandeya, Singhal & A.K.Bhatn.

- Chenopodium cycloides A. Nelson

- Chenopodium dacoticum Standl.

- Chenopodium deltaphyllum Osterh.

- Chenopodium deltoideum Lam.

- Chenopodium densifoliatum F. Dvořák

- Chenopodium desertorum (J. Black) J. Black

- Chenopodium desiccatum A. Nelson

- Chenopodium detestans Kirk

- Chenopodium dissectum Standl.

- Chenopodium diversifolium (Aellen) Dvořák

- Chenopodium drummondii (Moq.) S. Fuentes & Borsch

- Chenopodium dunosum L. Simón

- Chenopodium effusum M. Martens & Galeotti

- Chenopodium elatum Shuttlew. ex Moq.

- Chenopodium elegantissimum Koidz.

- Chenopodium eremaea (Paul G. Wilson) S. Fuentes & Borsch

- Chenopodium erosum R. Br.

- Chenopodium eustriatum F. Dvořák

- Chenopodium exocarpum Griseb.

- Chenopodium exsuccum (C. Loscos) Uotila

- Chenopodium farinosum (S. Watson) Standl.

- Chenopodium fasciculosum Aellen

- Chenopodium ferulatum Lunell

- Chenopodium ficifoliiforme Dvořák

- Chenopodium ficifolium Sm.

- Chenopodium filifolium Krock.

- Chenopodium filiforme Dumort.

- Chenopodium flabellifolium Standl.

- Chenopodium flavescens (Cav.) Schult.

- Chenopodium flavum Forssk.

- Chenopodium foetidum Lam.

- Chenopodium foggii Wahl

- Chenopodium foliosum (Moench) Asch.

- Chenopodium fremontii S. Watson

- Chenopodium frigidum Phil.

- Chenopodium frutescens C.A. Mey.

- Chenopodium fruticosum L.

- Chenopodium fueguianum Speg.

- Chenopodium furfuraceum Moq.

- Chenopodium fursajewii Aellen & Iljin

- Chenopodium gaudichaudianum (Moq.) Paul G. Wilson

- Chenopodium giganteum D. Don

- Chenopodium gigantospermum Aellen

- Chenopodium gigantum D. Don

- Chenopodium glabrescens (Aellen) Wahl

- Chenopodium glandulosum (Moq.) F. Muell.

- Chenopodium glaucophyllum Aellen

- Chenopodium glaucum L.

- Chenopodium glochidatum Gillies ex Moq.

- Chenopodium glomerulosum Rchb.

- Chenopodium gracilispicum H.W. Kung

- Chenopodium graveolens Willd.

- Chenopodium griseochlorinum F. Dvořák

- Chenopodium gubanovii Sukhor.

- Chenopodium guineense Jacq.

- Chenopodium halimus (L.) Thunb.

- Chenopodium halophilum Phil.

- Chenopodium hastatifolium Pandeya & A.Pandeya

- Chenopodium hastatum (L.) Dumort.

- Chenopodium haumanii Ulbr.

- Chenopodium hederiforme (Murr) Aellen

- Chenopodium helenense Aellen

- Chenopodium hians Standl.

- Chenopodium hircinum Schrad.

- Chenopodium hirsutum L.

- Chenopodium holopterum (Thell.) Thell. & Aellen

- Chenopodium hookerianum Moq.

- Chenopodium hortense Raddi ex Moq.

- Chenopodium hostii Ledeb.

- Chenopodium huanghoense C.P. Tsien & C.G. Ma

- Chenopodium hubbardii Aellen

- Chenopodium hubertusii F. Dvořák

- Chenopodium humile Hook.

- Chenopodium hybridum L.

- Chenopodium hypsophilum Hauman

- Chenopodium ilicifolium Griff.

- Chenopodium iljinii Golosk.

- Chenopodium inamoenum Standl.

- Chenopodium incanum (S. Watson) A. Heller

- Chenopodium incisum Poir.

- Chenopodium incognitum Wahl

- Chenopodium inflatum Aellen

- Chenopodium insulare J. Black

- Chenopodium integrifolium Vorosch.

- Chenopodium intermedium Mert. & W.D.J. Koch

- Chenopodium inurale L.

- Chenopodium jacquinii Ten.

- Chenopodium jenissejense Aell. & Iljin

- Chenopodium karoi (Murr) Aellen

- Chenopodium klinggraeffii (Abrom.) Aellen

- Chenopodium koraiense Nakai

- Chenopodium korshinskyi (Litv.) Minkw.

- Chenopodium laciniatum Roxb.

- Chenopodium lanceolatum Muhl. ex Willd.

- Chenopodium lanuginosum Moench

- Chenopodium laterale Aiton

- Chenopodium latifolium (Wahlenb.) E.H.L. Krause

- Chenopodium leiospermum DC.

- Chenopodium lenticulare Aellen

- Chenopodium leptophyllum (Moq.) B.D. Jacks.

- Chenopodium leucospermum Schrad.

- Chenopodium lhasaense C.P. Tsien & C.G. Ma

- Chenopodium linciense J. Murr

- Chenopodium lineare Steud.

- Chenopodium linifolium (Pall.) Roem. & Schult.

- Chenopodium littorale (L.) Thunb.

- Chenopodium littoreum Benet-Pierce & M.G. Simpson

- Chenopodium litwinowii (Paulsen) Uotila

- Chenopodium lobatum F. Dvořák

- Chenopodium lobodontum H. Scholz

- Chenopodium longidjawense Peter

- Chenopodium loureirei Steud.

- Chenopodium lucidum Gilib.

- Chenopodium lycioides Gand.

- Chenopodium macrocalycium Aellen

- Chenopodium macrocarpum Desv.

- Chenopodium macrospermum Hook. f.

- Chenopodium magellanicum Benth. & Hook. f.

- Chenopodium mairei H. Lév.

- Chenopodium mandonii (S. Watson) Aellen

- Chenopodium marginatum Spreng. ex Hornem.

- Chenopodium maritimum L.

- Chenopodium maroccanum Pau

- Chenopodium matthioli Bertol. ex Moq.

- Chenopodium mediterraneum F. Dvořák

- Chenopodium melanocarpum (J. Black) J. Black

- Chenopodium melanospermum Wallr.

- Chenopodium mexicanum Moq.

- Chenopodium microcarpum (Phil.) A. Tronc.

- Chenopodium microphyllum Thunb.

- Chenopodium microspermum Wallr.

- Chenopodium minimum P.Y. Fu & Wang-Wei

- Chenopodium minuatum Aellen

- Chenopodium missouriense Aellen

- Chenopodium moquinianum Aellen

- Chenopodium mucronatum Thunb.

- Chenopodium multifidum L.

- Chenopodium multiflorum Moq.

- Chenopodium murale L.

- Chenopodium myriocephalum (Benth.) Aellen

- Chenopodium neglectum Dumort.

- Chenopodium neoalbum F. Dvořák

- Chenopodium neomexicanum Standl.

- Chenopodium nepalense Colla

- Chenopodium nesodendron Skottsb.

- Chenopodium nevadense Standl.

- Chenopodium nidorosum Ochiauri

- Chenopodium nitens Benet-Pierce & M.G. Simpson

- Chenopodium nitrariaceum (F. Muell.) F. Muell. & Benth.

- Chenopodium novopokrovskyanum (Aellen) Uotila

- Chenopodium nudiflorum F. Muell. ex Murr

- Chenopodium nutans (R. Br.) S. Fuentes & Borsch

- Chenopodium nuttalliae Saff.

- Chenopodium oahuense Aellen

- Chenopodium oblanceolatum (Speg.) Giusti

- Chenopodium oblongifolium (S. Watson) Rydb.

- Chenopodium obovatum Moq.

- Chenopodium obscurum Aellen

- Chenopodium olidum Curtis

- Chenopodium olukondae Murr

- Chenopodium opulaceum Neck.

- Chenopodium opulifolium Schrad. ex W.D.J. Koch & Ziz

- Chenopodium orphanidis Murr

- Chenopodium osbornianum Aellen

- Chenopodium ovalifolium (Aellen) F. Dvořák

- Chenopodium overi Aellen

- Chenopodium paganum Rchb.

- Chenopodium pallasianum Schult.

- Chenopodium pallescens Standl.

- Chenopodium pallidicaule Aellen

- Chenopodium pallidum Moq.

- Chenopodium palmeri Standl.

- Chenopodium pamiricum Iljin

- Chenopodium paniculatum Hook.

- Chenopodium papulosum Moq.

- Chenopodium parabolicum (R. Br.) S. Fuentes & Borsch

- Chenopodium parodii Aellen

- Chenopodium parryi Standl.

- Chenopodium parvifolium Schult.

- Chenopodium patagonicum Phil.

- Chenopodium patulum Mérat

- Chenopodium paucidentatum (Aellen) F. Dvořák

- Chenopodium payco Molina

- Chenopodium pedunculare Bertol.

- Chenopodium pedunculatum (L.) E.H.L. Krause

- Chenopodium pekeloi Deg.,deg. & Aellen

- Chenopodium petiolare Kunth

- Chenopodium petiolariforme Aellen

- Chenopodium philippianum Aellen

- Chenopodium phillipianum Aellen

- Chenopodium phillipsianum Aellen

- Chenopodium physophora Moq. ex Boiss.

- Chenopodium physophorum (Pall.) Moq.

- Chenopodium pilcomayense Aellen

- Chenopodium pinnatum Moq.

- Chenopodium plantaginellum (F. Muell.) Aellen

- Chenopodium platyphyllum Issler

- Chenopodium polispermum Neck.

- Chenopodium polygonoides (Murr) Aellen

- Chenopodium polyspermum L.

- Chenopodium populifolium Moq.

- Chenopodium portulacoides (L.) Thunb.

- Chenopodium praeacutum Murr

- Chenopodium praecox C.P. Tsien

- Chenopodium pratericola Rydb.

- Chenopodium preissii (Moq.) Diels

- Chenopodium preissmannii Murr

- Chenopodium pringlei Standl.

- Chenopodium probstii Aellen

- Chenopodium procerum Hochst. ex Moq.

- Chenopodium prostratum (L.) Moq.

- Chenopodium pseudo-borbasii Murr

- Chenopodium pseudo-microphyllum Aellen

- Chenopodium pseudomultiflorum Uotila

- Chenopodium pseudopulifolium Murr. ex Hayward & Druce

- Chenopodium pueblense H.S. Reed

- Chenopodium pumilio R. Br.

- Chenopodium punctulatum Scop.

- Chenopodium purpurascens B. Juss. ex Jacq.

- Chenopodium pusillum Hook. f.

- Chenopodium pygmaeum Menyh.

- Chenopodium querciforme Murr

- Chenopodium quinoa Willd.

- Chenopodium radiatum Schrad.

- Chenopodium rafaelense Chodat & Wilczek

- Chenopodium reticulatum Aellen

- Chenopodium retortum Wang-Wei & P.Y. Fu

- Chenopodium retusum (Moq.) Moq.

- Chenopodium rhadinostachyum F. Muell.

- Chenopodium rhombifolium Muhl. ex Willd.

- Chenopodium rigidum Lingelsh.

- Chenopodium riparium Boenn. ex Moq.

- Chenopodium roseum (L.) E.H.L. Krause

- Chenopodium rostratum A.I. Baranov & Skvortsov

- Chenopodium rubrum L.

- Chenopodium ruderale Kit. ex Moq.

- Chenopodium ruiz-lealii Aellen

- Chenopodium sagittatum Lam.

- Chenopodium salinum Standl.

- Chenopodium salsum Guss.

- Chenopodium sancta-maria Vell.

- Chenopodium sanctae-clarae Johow

- Chenopodium sancti-ambrosii Skottsb.

- Chenopodium sandwicheum Moq.

- Chenopodium santamaria Vell.

- Chenopodium santoshei Pandeya, Singhal & A.K.Bhatn.

- Chenopodium savatieri Aellen

- Chenopodium saxatile Paul G. Wilson

- Chenopodium scabricaule Speg.

- Chenopodium schraderianum Schult.

- Chenopodium scoparia L.

- Chenopodium scoparium L.

- Chenopodium secundiflorum Viv.

- Chenopodium sericeum Spreng.

- Chenopodium serotinum L.

- Chenopodium setigerum DC.

- Chenopodium simplex (Torr.) Raf.

- Chenopodium simulans (F. Muell. & Tate ex Tate) F. Muell. & Tate ex F. Muell.

- Chenopodium sinense hort. ex Moq.

- Chenopodium sinuatum Thunb.

- Chenopodium solitarium Murr

- Chenopodium sooanum Aellen

- Chenopodium sosnowskyi Kapeller

- Chenopodium sparsiflorum Phil.

- Chenopodium spathulatum (Moq.) Sieber ex Moq.

- Chenopodium spegazzinii Dvořáková

- Chenopodium spicatum Schult.

- Chenopodium spinacifolium Stokes

- Chenopodium spinescens (R. Br.) S. Fuentes & Borsch

- Chenopodium spinosum Hook.

- Chenopodium standleyanum Aellen

- Chenopodium stellatum S. Watson

- Chenopodium stellulatum Aellen

- Chenopodium stenophyllum (Makino) Koidz.

- Chenopodium stramoniifolium Chev.

- Chenopodium striatiforme Murr

- Chenopodium striatum (Krašan) Murr

- Chenopodium strictum Roth

- Chenopodium stuckertii Gand.

- Chenopodium subaphyllum Phil.

- Chenopodium suberifolium Murr

- Chenopodium subficifolium (Murr) Druce

- Chenopodium subglabrum (S. Watson) A. Nelson

- Chenopodium subhastatum F. Dvořák

- Chenopodium subopulfolium Murr

- Chenopodium subspicatum Nutt.

- Chenopodium succosum A. Nelson

- Chenopodium suecicum J. Murr

- Chenopodium suffruticosum Willd.

- Chenopodium superalbum F. Dvořák

- Chenopodium tataricum (L.) E.H.L. Krause

- Chenopodium texanum Murr

- Chenopodium tibeticum A.J. Li

- Chenopodium tomentosum Thouars

- Chenopodium tonkinense Courchet

- Chenopodium tournefortianum Moq.

- Chenopodium tournefortii Moq.

- Chenopodium triandrum G. Forst.

- Chenopodium triangulare Forssk.

- Chenopodium triangularifolia Gilib.

- Chenopodium tridentinum Murr

- Chenopodium trigonon Schult.

- Chenopodium trigynum Schult.

- Chenopodium trilobum Schult. ex Moq.

- Chenopodium truncatum Paul G. Wilson

- Chenopodium tuberosum Ruiz

- Chenopodium tweedii Moq.

- Chenopodium ugandae Aellen

- Chenopodium ulbrichii Aellen

- Chenopodium ulicinum Gand.

- Chenopodium uljinii Golosk.

- Chenopodium urbicum L.

- Chenopodium vachelii Hook. & Arn.

- Chenopodium vachellii Hook. & Arn.

- Chenopodium variabile Aellen

- Chenopodium variegatum Gouan

- Chenopodium venturii (Aellen) Cabrera

- Chenopodium vestitum Thunb.

- Chenopodium villosum Lam.

- Chenopodium virgatum Thunb.

- Chenopodium virginicum L.

- Chenopodium viride L.

- Chenopodium viridescens Dalla Torre & Sarnth.

- Chenopodium vulgare Gueldenst. ex Ledeb.

- Chenopodium vulvaria L.

- Chenopodium watsonii A. Nelson

- Chenopodium wilsonii S. Fuentes see Fuentes-Bazan Susy, Borsch & Uotila

- Chenopodium wolffii Simonk.

- Chenopodium wolfii Simonk.

- Chenopodium x Bontei Aell.

- Chenopodium zachae F. Dvořák

- Chenopodium zerovii Iljin

- Chenopodium zobelli A. Ludw. & Aellen

- Chenopodium zoellneri Aellen

- Chenopodium zosterifolium Hook.

- Chenopodium zschackei Murr

- Chenopodium × binzianum Aellen & Thell.

- Chenopodium × bohemicum F. Dvořák

- Chenopodium × bontei Aellen

- Chenopodium × brunense F. Dvořák

- Chenopodium × christii Aellen

- Chenopodium × covillei Aellen

- Chenopodium × dadakovae F. Dvořák

- Chenopodium × densifoliatum (Ludw. & Aellen) F. Dvořák

- Chenopodium × densifolium (Ludwig & Aellen) F. Dvořák

- Chenopodium × fallax F. Dvořák

- Chenopodium × hubertusii F. Dvořák

- Chenopodium × humiliforme F. Dvořák

- Chenopodium × jedlickae F. Dvořák

- Chenopodium × jehlikii F. Dvořák

- Chenopodium × leptophylliforme Aellen

- Chenopodium × linciense Murr

- Chenopodium × mendelii F. Dvořák

- Chenopodium × podperae F. Dvořák

- Chenopodium × praeacutum Murr

- Chenopodium × pseudoleptophyllum Aellen

- Chenopodium × pseudostriatum (Zschacke) Druce

- Chenopodium × rhombicum (Murr) F. Dvořák

- Chenopodium × schulzeanum Murr

- Chenopodium × schwarzovae F. Dvořák

- Chenopodium × smardae F. Dvořák

- Chenopodium × subhastatum (Issler ex Murr) F. Dvořák

- Chenopodium × tapolczense F. Dvořák

- Chenopodium × tkalcsicsii H. Melzer

- Chenopodium × trigonocarpum Aellen

- Chenopodium × unarii F. Dvořák

- Chenopodium × variabile Aellen

Les chénopodes dans le langage courant

Dans le langage courant ces plantes sont connues sous des noms tels que le chénopode blanc (Chenopodium album L.), tandis que d'autres chénopodes sont éventuellement classés par les botanistes dans d'autres genres comme le chénopode bon-Henri ou épinard sauvage (Blitum bonus-henricus (L.) Rchb.[12], syn. Chenopodium bonus-henricus L.) ou l'épazote (Dysphania ambrosioides (L.) Mosyakin & Clemants[15], syn. Chenopodium ambrosioides L.).

Notes et références

- IPNI. International Plant Names Index. Published on the Internet http://www.ipni.org, The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Harvard University Herbaria & Libraries and Australian National Botanic Gardens., consulté le 13 juillet 2020

- (en) Aly M. El-Sayed, M. A. Al-Yahya et Mahmoud M. A. Hassan, « Chemical Composition and Antimicrobial Activity of the Essential Oil of Chenopodium botrys Growing in Saudi Arabia », International Journal of Crude Drug Research, vol. 27, no 4, , p. 185–188 (ISSN 0167-7314, DOI 10.3109/13880208909116900, lire en ligne, consulté le )

- (en) Renata Nowak, Katarzyna Szewczyk, Urszula Gawlik-Dziki et Jolanta Rzymowska, « Antioxidative and cytotoxic potential of some Chenopodium L. species growing in Poland », Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences, vol. 23, no 1, , p. 15–23 (PMID 26858534, PMCID PMC4705297, DOI 10.1016/j.sjbs.2015.01.017, lire en ligne, consulté le )

- Paul Fournier, Les quatre flores de France : Corse comprise (Générale, Alpine, Méditerranéenne, Littorale), Paris, Lechevalier, , 1104 p. (ISBN 978-2-7205-0529-4), p. 251

- (en) Ahmed A. Gohara et M. M. A. Elmazar, « Isolation of hypotensive flavonoids fromChenopodium species growing in Egypt », Phytotherapy Research, vol. 11, no 8, , p. 564–567 (ISSN 0951-418X et 1099-1573, DOI 10.1002/(sici)1099-1573(199712)11:8<564::aid-ptr162>3.0.co;2-l, <564::aid-ptr162>3.0.co;2-l lire en ligne, consulté le )

- (en) Ritva Repo-Carrasco-Valencia, Jarkko K. Hellström, Juha-Matti Pihlava et Pirjo H. Mattila, « Flavonoids and other phenolic compounds in Andean indigenous grains: Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa), kañiwa (Chenopodium pallidicaule) and kiwicha (Amaranthus caudatus) », Food Chemistry, vol. 120, no 1, , p. 128–133 (ISSN 0308-8146, DOI 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.09.087, lire en ligne, consulté le )

- (en) A. Bhargava, S. Shukla et D. Ohri, « Analysis of Genotype × Environment Interaction for Grain Yield in Chenopodium spp. », Czech Journal of Genetics and Plant Breeding, vol. 41, no No. 2, , p. 64–72 (ISSN 1212-1975 et 1805-9325, DOI 10.17221/3673-cjgpb, lire en ligne, consulté le )

- (en) Menka Khoobchandani, B. K. Ojeswi, Bhavna Sharma et Man Mohan Srivastava, « Chenopodium AlbumPrevents Progression of Cell Growth and Enhances Cell Toxicity in Human Breast Cancer Cell Lines », Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, vol. 2, no 3, , p. 160–165 (ISSN 1942-0900 et 1942-0994, DOI 10.4161/oxim.2.3.8837, lire en ligne, consulté le )

- (en) Ashish Baldi et NaveenKumar Choudhary, « In vitro antioxidant and hepatoprotective potential of chenopodium album extract », International Journal of Green Pharmacy, vol. 7, no 1, , p. 50 (ISSN 0973-8258, DOI 10.4103/0973-8258.111614, lire en ligne, consulté le )

- (en) Urszula Gawlik-Dziki, Michał Świeca, Maciej Sułkowski et Dariusz Dziki, « Antioxidant and anticancer activities of Chenopodium quinoa leaves extracts – In vitro study », Food and Chemical Toxicology, vol. 57, , p. 154–160 (ISSN 0278-6915, DOI 10.1016/j.fct.2013.03.023, lire en ligne, consulté le )

- (en) Margarita Miranda, José Delatorre-Herrera, Antonio Vega-Gálvez et Evelyn Jorquera, « Antimicrobial Potential and Phytochemical Content of Six Diverse Sources of Quinoa Seeds (<i>Chenopodium quinoa</i> Willd.) », Agricultural Sciences, vol. 05, no 11, , p. 1015–1024 (ISSN 2156-8553 et 2156-8561, DOI 10.4236/as.2014.511110, lire en ligne, consulté le )

- USDA, Agricultural Research Service, National Plant Germplasm System. Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN-Taxonomy). National Germplasm Resources Laboratory, Beltsville, Maryland., consulté le 27 septembre 2015

- Chenopodium bonus-henricus L. sur le site du National Plant Germplasm System, consulté le 18 février 2016.

- Tropicos.org. Missouri Botanical Garden., consulté le 27 septembre 2015

- The Plant List (2013). Version 1.1. Published on the Internet; http://www.theplantlist.org/, consulté le 27 septembre 2015

Voir aussi

Liens externes

- (en) Référence IPNI : Chenopodium

- (en) Référence Flora of North America : Chenopodium (consulté le )

- (en) Référence Flora of China : Chenopodium (consulté le )

- (en) Référence Madagascar Catalogue : Chenopodium (consulté le )

- (en) Référence FloraBase (Australie-Occidentale) : classification Chenopodium (+ photos + répartition + description) (consulté le )

- (en) Référence GRIN : genre Chenopodium L. (+liste d'espèces contenant des synonymes) (consulté le )

- (fr+en) Référence ITIS : Chenopodium L. (consulté le )

- (en) Référence NCBI : Chenopodium (taxons inclus) (consulté le )

- (en) Référence The Plant List : Chenopodium (consulté le )

- (en) Référence Tropicos : Chenopodium L. (+ liste sous-taxons) (consulté le )

- (en) Référence World Register of Marine Species : taxon Chenopodium (+ liste espèces) (consulté le )

- (fr) Référence Tela Botanica (France métro) : Chenopodium L.