Point chaud de Yellowstone

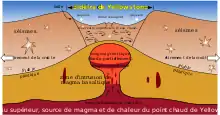

Le point chaud de Yellowstone (Yellowstone hotspot), également appelé point chaud de Snake River Plain-Yellowstone (Snake River Plain-Yellowstone hotspot), est un point chaud volcanique situé à Yellowstone, aux États-Unis. Il est la cause d'événements volcaniques d'importance dans les États de l'Oregon, du Nevada, de l'Idaho et du Wyoming. Il a créé une série de caldeiras, dont la Island Park Caldera, la Henry's Fork Caldera (en) et la Bruneau-Jarbidge caldera (en), qui ont formé la Snake River Plain. Le point chaud est actuellement sous la caldeira de Yellowstone[1].

| N° sur la carte |

44 |

|---|---|

| Type | |

| Existence |

Possible (d) |

| Vélocité |

26 mm/an |

|---|---|

| Direction |

235 ° |

| Plaque | |

|---|---|

| Coordonnées |

44° 30′ N, 110° 24′ O |

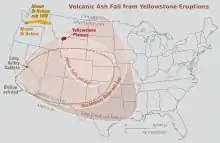

La plus récente superéruption du point chaud, connue sous le nom de l'éruption de Lava Creek, s'est produite il y a environ 640 000 ans et a formé le tuf de Lava Creek ainsi que la caldeira de Yellowstone.

Histoire

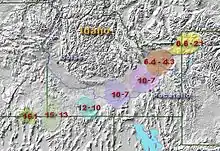

La liste suivante recense les événements géologiques d'importance rattachés au point chaud de Yellowstone. La datation des événements dans le passé est donnée en milliers d'années (ka) ou en millions d'années (Ma). Parfois, l'indice d'explosivité volcanique (VEI), une estimation du volume de lave impliquée (en km3) et l'étendue de l'écoulement sont donnés.

| Nom de la structure | Lieu | Datation | VEI | Volume éjecté | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monument national et réserve nationale Craters of the Moon | nord-est de Rupert (Idaho) | 2,270 ± 0,15 ka | [2] | ||

| Hell's Half Acre Lava Field (en) | de l'ouest jusqu'au sud-ouest de Idaho Falls | 3,250 ± 0,15 ka | [3] | ||

| Shoshone lava field (en) | nord de Twin Falls | 8,400 ± 0,3 ka | [4] | ||

| Monument national et réserve nationale Craters of the Moon | 2-15 ka | Le champ de lave s'est formé lors de huit épisodes éruptifs qui se sont produits il y a 2 à 15 ka[5]. Les champs de lave Kings Bowl et Wapi se sont formés il y a environ 2,25 ka[6]. | |||

| Caldeira de Yellowstone | Parc national de Yellowstone | 70-150 ka | 1 000 km3 | Coulées de lave rhyolitique à l'intérieur de la caldeira[7] | |

| Caldeira de Yellowstone (Lava Creek Tuff) | Parc national de Yellowstone | 640 ka | 8 | ~1 000 km3 (étendue de 45 x 85 km) | [7] |

| Henry's Fork Caldera (en) (Mesa Falls Tuff (en)) | Island Park Caldera et Harriman State Park (en) | 1,3 Ma | 7 | 280 km3 (étendue de 16 km) | [7] |

| Island Park Caldera (Huckleberry Ridge Tuff (en)) | 2,1 Ma | 8 | 2 450 km3 (étendue : 100 x 50 km) | [7] - [8] | |

| Kilgore Caldera (tuff de Kilgore) | Champ volcanique Heise Idaho | 4,45 ± 0,05 Ma | 8 | 1 800 km3 (étendue : 80 x 60 km) | [9] - [8] |

| tuff de Heise | Champ volcanique Heise Idaho | 4,49 Ma | [10] | ||

| tuff d'Elkhorn Springs | Champ volcanique Heise, Idaho | 5,37 Ma | [8] | ||

| tuff de Conant Creek | Champ volcanique Heise, Idaho | 5,51 ± 0,13 Ma (5,94 Ma selon Anders 2009) | [9] - [10] | ||

| tuff de Blue Creek | Champ volcanique Heise, Idaho | 5,6 Ma | 500 km3 | [8] | |

| tuff de Wolverine Creek | Champ volcanique Heise, Idaho | 5,81 Ma | [10] | ||

| tuff de Walcott | Champ volcanique Heise, Idaho | 6,27 ± 0,04 Ma | [9] | ||

| tuff de Edi School | Champ volcanique Heise, Idaho | 6,57 Ma | [10] | ||

| Blacktail Caldera (tuff de Blacktail) | Champ volcanique Heise, Idaho | 6,62 ± 0,03 Ma | 1 500 km3 (étendue : 100 x 60 km) | [9] - [8] | |

| tuff d'America Falls | 7,48 Ma | [10] | |||

| tuff de Lost River Sinks | 8,75 Ma | [10] | |||

| tuff de Kyle Canyon | 9,17 Ma | [10] | |||

| tuff de Little Chokecherry Canyon | 9,34 Ma | [10] | |||

| champ volcanique de Twin Falls | Comté de Twin Falls | 8,6 à 10 Ma | [10] | ||

| champ volcanique Picabo (tuff d'Arbon Valley) | Picabo (Idaho) (en) | 10,09 Ma (Tuff A) 10,21 ± 0,03 Ma (Tuff B) | [9] - [10] | ||

| champ volcanique de la caldeira de Bruneau-Jarbidge (en) | Bruneau Jarbidge River (en) Idaho | 10,0 à 12,5 Ma | Créé lors de l'éruption des Ashfall Fossil Beds (en)[10]. | ||

| champ volcanique Owyhee-Humboldt | Comté d'Owyhee, Nevada Oregon | 12,8 à 13,9 Ma | [10] | ||

| champ volcanique McDermitt | Orevada rift, McDermitt (Nevada-Oregon) (en) Nevada-Oregon | 15-16,1 Ma | superficie de 20 000 km2 | Constitué de sept caldeiras[11]. | |

| Whitehorse Caldera (tuff de Whitehorse Creek) | Trout Creek Mountains (en) Est des Pueblo Mountains (en) Oregon | 15 Ma | 40 km3 (étendue : 15 km) | [8] - [12] | |

| Jordan Meadow Caldera (tuff 2-3 de Longridge) | 15,6 Ma | 350 km3 (étendue : 10–15 km) | [8] - [10] - [12] - [13] | ||

| Longridge Caldera (tuff 5 de Longridge) | 15,6 Ma | 400 km3 (étendue : 33 km) | [8] - [10] - [12] - [13] | ||

| Calavera Caldera (tuff de Double H) | 15,7 Ma | 300 km3 (étendue : 17 km) | [8] - [10] - [12] - [13] | ||

| Pueblo Caldera (tuff de Trout Creek Mountains) | Trout Creek Mountains Oregon | 15,8 Ma | 40 km3 (étendue : 20 x 10 km) | [8] - [12] - [14] | |

| Hoppin Peaks Caldera (Hoppin Peaks Tuff) | 16 Ma | [14] | |||

| Washburn Caldera (Oregon Canyon Tuff) | Oregon | 16,548 Ma | 250 km3 (étendue : 30 x 25 km) | [8] - [12] - [13] | |

| champ volcanique de Lake Owyhee (en) | 15,0 à 15,5 Ma | [15] | |||

| caldeiras Virgin Valley, High Rock, Hog Ranch et autres (tuffs d'Idaho Canyon, Ashdown, Summit Lake et Soldier Meadow) | champ volcanique du nord-ouest du Nevada ouest de Pine Forest Range (en) | 15,5 à 16,5 Ma | [16] - [17] - [18] - [19] - [20] | ||

| Columbia River Basalt Province | Groupe basaltique de Columbia River et Steens flood. Pueblo et la région de Malheur Gorge Pueblo Mountains (en), Steens Mountain Washington, Oregon et Idaho | 14 à 17 Ma | 180 000 km3 | Série d'éruptions dont les plus intenses se sont produites il y a 14 à 17 Ma[8] - [21] - [22] - [23] - [24] - [25] - [26] - [27] | |

| Groupe basaltique du Columbia | 175 000 km3 | [28] - [29] - [30] | |||

| Basaltes de Steens flood | 65 000 km3 | [28] - [31] - [32] | |||

| Siletz River Volcanics (en) Chaîne côtière de l'Oregon | Crescent volcanics Péninsule Olympique Sud de l'Île de Vancouver | 50-60 Ma | Une série de coulées de lave en coussins basaltique[33]. | ||

| Carmacks Group (en) | Yukon | 70 Ma | 63 000 km2 | [34] - [35] - [36] |

Notes et références

- (en) Cet article est partiellement ou en totalité issu de l’article de Wikipédia en anglais intitulé « Yellowstone hotspot » (voir la liste des auteurs).

- (en) « Yellowstone Caldera, Wyoming, USGS ».

- « The Great Rift Zone », sur isu.edu (consulté le ).

- (en) « Hell's Half Acre », sur https://volcano.si.edu, Global Volcanism Program, Smithsonian Institution (consulté le ).

- (en) « Shoshone Lava Field », sur https://volcano.si.edu, Global Volcanism Program, Smithsonian Institution (consulté le ).

- (en) « Craters of the Moon », sur https://volcano.si.edu, Global Volcanism Program, Smithsonian Institution (consulté le ).

- (en) « Wapi Lava Field », sur https://volcano.si.edu, Global Volcanism Program, Smithsonian Institution (consulté le ).

- (en) « Yellowstone », sur https://volcano.si.edu, Global Volcanism Program, Smithsonian Institution (consulté le ).

- (en) « Supplementary Table to P.L. Ward, Thin Solid Films (2009) Major volcanic eruptions and provinces », Teton Tectonics (consulté le ).

- (en)Lisa A. Morgan and William C. McIntosh, « Timing and development of the Heise volcanic field, Snake River Plain, Idaho, western USA », Geological Society of America Bulletin, vol. 117, nos 3–4, , p. 288–306 (DOI 10.1130/B25519.1, Bibcode 2005GSAB..117..288M, lire en ligne).

- (en) « Mark H. Anders, associate professor: Yellowstone hotspot track », Columbia University, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory (LDEO) (consulté le ).

- (en) James J Rytuba et Edwin H. McKee, « Peralkaline Ash Flow Tuffs and Calderas of the McDermitt Volcanic Field, Southeast Oregon and North Central Nevada »(Archive.org • Wikiwix • Archive.is • Google • Que faire ?) [abstract] (consulté le ) : « The McDermitt volcanic field covers an area of 20,000 km2 in southeastern Oregon and northwestern Nevada and consists of seven large-volume ash flow sheets that vented from 16.1 to 15 Ma ago ».

- (en)P.W. Lipman, « The Roots of Ash Flow Calderas in Western North America: Windows Into the Tops of Granitic Batholiths », Journal of Geophysical Research, vol. 89, no B10, , p. 8801–8841 (DOI 10.1029/JB089iB10p08801, Bibcode 1984JGR....89.8801L).

- (en)Steve Ludington, Dennis P. Cox, Kenneth W. Leonard, and Barry C. Moring, « An Analysis of Nevada's Metal-Bearing Mineral Resources », Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology, University of Nevada, .

- (en)J.J. Rytuba et McKee, E.H., « Peralkaline ash flow tuffs and calderas of the McDermitt Volcanic Field, southwest Oregon and north central Nevada », Journal of Geophysical Research, vol. 89, no B10, , p. 8616–8628 (DOI 10.1029/JB089iB10p08616, Bibcode 1984JGR....89.8616R, lire en ligne, consulté le ).

- (en)James J. Rytuba, John, David A. et McKee, Edwin H., « Volcanism Associated with Eruption of the Steens Basalt and Inception of the Yellowstone Hotspot », Rocky Mountain (56th Annual) and Cordilleran (100th Annual) Joint Meeting, vol. Paper No. 44-2, may 3–5, 2004 (lire en ligne, consulté le ).

- (en) Matthew A. Coble et Gail A. Mahood, « New geologic evidence for additional 16.5-15.5 Ma silicic calderas in northwest Nevada related to initial impingement of the Yellowstone hot spot », Earth and Environmental Science 3, Collapse Calderas Workshop, IOP Conf. Series, (DOI 10.1088/1755-1307/3/1/012002, lire en ligne).

- (en)D.C. Noble, « Spring Field Trip Guidebook, Special Publication No. 7 », Geological Society of Nevada, , p. 31–42.

- (en)Castor, S.B., and Henry, C.D., « Geology, geochemistry, and origin of volcanic rock-hosted uranium deposits in northwest Nevada and southeastern Oregon, USA », Ore Geology Review, vol. 16, , p. 1–40 (DOI 10.1016/S0169-1368(99)00021-9).

- (en)Marjorie K. Korringa, « Linear vent area of the Soldier Meadow Tuff, an ash-flow sheet in northwestern Nevada », Geological Society of America Bulletin, vol. 84, no 12, , p. 3849–3866 (DOI 10.1130/0016-7606(1973)84<3849:LVAOTS>2.0.CO;2, Bibcode 1973GSAB...84.3849K, lire en ligne).

- (en)Matthew E. Brueseke and William K. Hart, « Geology and Petrology of the Mid-Miocene Santa Rosa-Calico Volcanic Field, Northern Nevada », Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology, vol. Bulletin 113, , p. 44 (lire en ligne [archive du ]).

- (en) Robert J. Carson et Kevin R. Pogue, Flood Basalts and Glacier Floods : Roadside Geology of Parts of Walla Walla, Franklin, and Columbia Counties, Washington, Washington State Department of Natural Resources (Washington Division of Geology and Earth Resources Information Circular 90), .

- (en)Stephen P. Reidel, « A Lava Flow without a Source: The Cohasset Flow and Its Compositional Members », The Journal of Geology, vol. 113, , p. 1–21 (DOI 10.1086/425966, Bibcode 2005JG....113....1R).

- (en)M.E. Brueseke, « Distribution and geochronology of Oregon Plateau (U.S.A.) flood basalt volcanism: The Steens Basalt revisited », Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, vol. 161, no 3, , p. 187–214 (DOI 10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2006.12.004, Bibcode 2007JVGR..161..187B).

- (en)SummitPost.org, Southeast Oregon Basin and Range.

- USGS, Andesitic and basaltic rocks on Steens Mountain.

- (en)GeoScienceWorld, Genesis of flood basalts and Basin and Range volcanic rocks from Steens Mountain to the Malheur River Gorge, Oregon.

- (en) « Oregon: A Geologic History. 8. Columbia River Basalt: the Yellowstone hot spot arrives in a flood of fire », Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries (consulté le ).

- (en) « High Lava Plains Project, Geophysical & Geological Investigation, Understanding the Causes of Continental Intraplate Tectonomagmatism: A Case Study in the Pacific Northwest » [archive du ], Department of Terrestrial Magnetism, Carnegie Institution of Washington (consulté le ).

- (en)Tolan, T.L., Reidel, S.P., Beeson, M.H., Anderson, J.L., Fecht, K.R. and Swanson, D.A., « Volcanism and tectonism in the Columbia River flood basalt province », Geol. Soc. Amer. Spec. Paper, vol. 239, , p. 1–20.

- (en)Camp, V.E., and Ross, M.E., « Mantle dynamics and genesis of mafic magmatism in the intermontane Pacific Northwest », Journal of Geophysical Research, vol. 109, no B08204, , B08204 (DOI 10.1029/2003JB002838, Bibcode 2004JGRB..10908204C).

- (en)Carlson, R.W. and Hart, W.K., « Crustal Genesis on the Oregon Plateau », Journal of Geophysical Research, vol. 92, no B7, , p. 6191–6206 (DOI 10.1029/JB092iB07p06191, Bibcode 1987JGR....92.6191C).

- (en)Hart, W.K., and Carlson, R.W., « Distribution and geochronology of Steens Mountain-type basalts from the northwestern Great Basin », Isochron/West, vol. 43, , p. 5–10.

- (en)J. Brendan Murphy, Andrew J. Hynes, Stephen T. Johnston et J. Duncan Keppie, « Reconstructing the ancestral Yellowstone plume from accreted », Tectonophysics, vol. 365, , p. 185– 194 (DOI 10.1016/S0040-1951(03)00022-2, Bibcode 2003Tectp.365..185M, lire en ligne, consulté le ).

- (en)Stephen T. Johnston, P. Jane Wynne, Don Francis, Craig J. R. Hart, Randolph J. Enkin et David C. Engebretson, « Yellowstone in Yukon: The Late Cretaceous Carmacks Group », Geology, vol. 24, no 11, , p. 997–1000 (DOI 10.1130/0091-7613(1996)024<0997:YIYTLC>2.3.CO;2, Bibcode 1996Geo....24..997J, lire en ligne, consulté le ).

- (en)P. J. A. McCausland, D. T. A. Symons et C. J. R. Hart, « Rethinking "Yellowstone in Yukon" and Baja British Columbia: Paleomagnetism of the Late Cretaceous Swede Dome stock, northern Canadian Cordillera », Journal Geophysical Research, vol. 110, no B12107, , p. 13 (DOI 10.1029/2005JB003742, Bibcode 2005JGRB..11012107M).

- (en) « O Ma large mafic magmatic events » [archive du ], www.largeigneousprovinces.org (consulté le ).

Références pour les cartes

- (en) Mark H. Anders, « Yellowstone hotspot track », Columbia University, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory (LDEO) (consulté le )

- (en) « Map of Nevada » [archive du ], Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology, University of Nevada (NBMG) (consulté le )

- (en) « Shaded relief map of the northwestern United States » [archive du ], Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology, University of Nevada (NBMG) (consulté le )

Voir aussi

Articles connexes

Bibliographie

![]() : document utilisé comme source pour la rédaction de cet article.

: document utilisé comme source pour la rédaction de cet article.

- (en)Robert B. Smith, « Geodynamics of the Yellowstone hotspot and mantle plume: Seismic and GPS imaging, kinematics and mantle flow », Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, vol. 188, nos 1–3, , p. 26–56 (DOI 10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2009.08.020, lire en ligne)

- (en)Katrina R. DeNosaquo, Robert B. Smith et Anthony R. Lowry, « Density and lithospheric strength models of the Yellowstone-Snake River Plain volcanic system from gravity and heat flow data », Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, vol. 188, nos 1–3, , p. 108–127 (DOI 10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2009.08.006)

- (en)Jamie Farrell, Stephan Husen et Robert B. Smith, « Earthquake swarm and b-value characterization of the Yellowstone volcano-tectonic system », Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, vol. 188, nos 1–3, , p. 260–276 (DOI 10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2009.08.008)

- (en)Michael E. Perkins et Barbara P. Nash, « Explosive silicic volcanism of the Yellowstone hotspot: the ash fall tuff record », The Geological Society of America Bulletin, vol. 114, no 3, , p. 367–381 (DOI 10.1130/0016-7606(2002)114<0367:ESVOTY>2.0.CO;2, Bibcode 2002GSAB..114..367P)

- (en)C.M. Puskas, R.B. Smith, C.M. Meertens et W.L. Chang, « Crustal deformation of the Yellowstone-Snake River Plain volcanic system: campaign and continuous GPS observations, 1987–2004 », Journal of Geophysical Research, vol. 112, no B03401, , B03401 (DOI 10.1029/2006JB004325, Bibcode 2007JGRB..11203401P)