Marie d'Argyll

Maria de Ergadia c'est-à-dire Marie d'Argyll (morte 1302) est une noble écossaise du XIIIe siècle qui fut reine du royaume de Man et des Îles puis comtesse de Strathearn.

| Comtesse |

|---|

| Décès | |

|---|---|

| Sépulture |

Greyfriars, London (en) |

| Famille | |

| Père | |

| Conjoints |

Malise II de Strathearn (à partir de ) Hugh of Abernethy (d) (à partir de ) William FitzWarin Magnús Óláfsson |

| Enfant |

Alexander de Abernethy (en) |

Mariages multiples

Maria est la file de Eóghan Mac Dubhghaill, seigneur d'Argyll (mort c.1268 × 1275), et ainsi une membre du Clann Dubhghaill[2].

Elle contracte pas moins de quatre unions successives avec: Magnús Óláfsson, roi de Man et des Îles (mort en 1265)[3], Maol Íosa II de Strathearn (mort en 1271)[4], Hugh, seigneur d'Abernethy (mort en 1291/1292)[5], et William FitzWarin (mort en 1299)[6]. Ces unions remarquables révèlent la politique matrimoniale de haut rang à laquelle avait accès les membres Clann Dubhghaill[7].

On ignore quand Maria épouse son premier mari[8]. La dernière mention de son père dans les sources se situe en 1268, lorsqu'il est témoin d'une charte de Maol Íosa. Il est possible que c'est vers cette époque que Maria épouse ce dernier[9].La même année les sources notent que Maol Íosa a obtenu un prêt de 62 livres du roi d'Écosse[10], une somme qui est sans doute en rapport avec son mariage[11]. Les comtes de Strtathearn sont parmi les plus puissants magnats du royaume d'Écosse, et il est probable que le mariage de Maol Íosa avec la veuve du roi de Man et des Îles contribue à sa puissance et renforce son prestige[12]. De ce fait pendant une grande partie de sa vie, Maria porte le titre de « Comtesse de Strathearn »[13].

Maria et son troisième époux, Hugh, ont plusieurs enfants[14].Un de ses fils avec Hugh est Alexandre[15]. Après la mort d'Hugh, Maria est convoquée devant le parlement pour justifier les droits d'Alexandre sur divers domaines[16]. En 1292, Maria s'endette envers Nicholas de Meynell de 200 marks, une partie de la dot d'une de ses filles[13]. Lorsque Maria rend l’hommage au roi Édouard Ier en 1296, elle se dénomme elle-même « la Reẏne de Man »[17]. La date du quatrième mariage de Maria est également inconnue, toutefois on sait que son quatrième mari meurt en 1299[18].

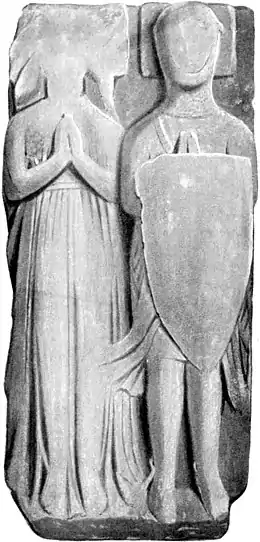

Cette année là, Maria reçoit sa part des possessions de William et son douaire d'Alan, un fils de William né d'une précédente union. Sa part de douaire comprend le garde et l'organisation du mariage de John, fils de Alan Logan[19]. In 1300, John de Lyndeby, Prieur de Holmcultram est nommé son avocat et reçoit pour elle son douaire en Irlande[20]. En 1302, Maria meurt à Londres entourée de ses parents du Clann Dubhghaill[21], elle est inhumée aux côtes de William dans l'église des Frères mineurs conventuels de la cité[22]. Un gisant représentant son second époux et peut-être de Maria elle-même se trouve également dans la cathédrale de Dunblane[1].

Références

- (en) Cet article est partiellement ou en totalité issu de l’article de Wikipédia en anglais intitulé « Maria de Ergadia » (voir la liste des auteurs).

- Holton (2017) pp. 196–197; Neville (1983a) p. 116; Brydall (1894–1895) pp. 350, 351 fig. 14.

- Holton (2017) p. xviii fig. 2; Sellar (2004); Sellar (2000) p. 94 tab. ii.

- Holton (2017) pp. xviii fig. 2, 140; Higgit (2000) p. 19; Sellar (2004); Sellar (2000) pp. 205–206 n. 96; Duffy (1993) p. 158; Neville (1983a) p. 112; Barrow (1981) p. 130; Paul (1911) p. 246; Paul (1902) pp. 19–20; Bain (1884) p. 124 § 508; Turnbull (1842) p. 109; Rymer; Sanderson (1816) p. 773; Rotuli Scotiæ in Turri Londinensi (1814) p. 26.

- Holton (2017) pp. xviii fig. 2; Higgit (2000) p. 19; Sellar (2004); Sellar (2000) pp. 205–206 n. 96; Cowan (1990) p. 122; Neville (1983a) pp. 112–113; Barrow (1981) p. 130; Cokayne; White (1953) pp. 382–383; Paul (1902) pp. 19–20; Bain (1884) pp. 124 § 508, 285 § 1117, 437 § 1642; Turnbull (1842) p. 109; Rymer; Sanderson (1816) p. 773; RPS, 1293/2/10 (n.d.); RPS, 1293/2/10 (n.d.).

- Beam (2008) p. 132 n. 59; McQueen (2002) pp. 148–149 n. 23; Higgit (2000) p. 19; Sellar (2004); Sellar (2000) pp. 205–206 n. 96; Neville (1983a) p. 113; Barrow (1981) p. 137; Cokayne; White (1953) p. 383; Paul (1911) pp. 246–247; Paul (1902) p. 19; Bliss (1893) p. 463; Theiner (1864) p. 125 § 277; The Acts of the Parliaments of Scotland (1844) p. 446; Rotuli Scotiæ in Turri Londinensi (1814) p. 26; PoMS, H2/152/1 (n.d.); PoMS Transaction Factoid, No. 38476 (n.d.); RPS, 1293/2/10 (n.d.); RPS, 1293/2/10 (n.d.).

- Sellar (2004); Higgit (2000) p. 19; Sellar (2000) pp. 205–206 n. 96; Duffy (1993) p. 158; Watson (1991) p. 245; Neville (1983a) p. 113; Cokayne; White (1953) p. 383; Paul (1911) p. 247; Paul (1902) p. 20; Henderson (1898); Bain (1884) pp. 270 § 1062, 280 § 1104, 285 § 1117, 437 § 1642; Sweetman (1881) p. 330 § 698.

- Sellar (2004).

- Holton (2017) p. 141.

- Holton (2017) p. 144; Sellar (2000) p. 205; Neville (1983a) p. 112; Neville (1983b) pp. 98–100 § 53; Cokayne; White (1953) p. 382, 382 n. p; Paul (1911) p. 246, 246 n. 10; Lindsay; Dowden; Thomson (1908) pp. 86–87 § 96.

- Neville (1983a) pp. 112, 239.

- Neville (1983a) p. 112.

- Neville (1983a) p. 240.

- Neville (1983a) p. 113.

- Sellar (2000) pp. 205–206 n. 96; Cokayne; White (1953) p. 383 n. a; Bliss (1893) p. 463.

- Beam (2008) p. 132 n. 59; McQueen (2002) p. 149 n. 23.

- Beam (2008) p. 132 n. 59; McQueen (2002) pp. 148–149, 149 n. 23; The Acts of the Parliaments of Scotland (1844) p. 446; RPS, 1293/2/10 (n.d.); RPS, 1293/2/10 (n.d.).

- Holton (2017) p. 140 n. 76; Neville (1983a) p. 113; Bain (1884) p. 212; Instrumenta Publica (1834) p. 164; PoMS, H6/2/0 (n.d.); PoMS Transaction Factoid, No. 79965 (n.d.).

- Duffy (1993) p. 158.

- Duffy (1993) pp. 158, 160, 205; Sweetman (1881) p. 330 § 698.

- Duffy (1993) p. 158 n. 39; Calendar of Chancery Warrants (1927) p. 115.

- Sellar (2000) pp. 205–206 n. 96; Neville (1983a) p. 113; Simpson; Galbraith (n.d.) p. 173 § 290.

- Higgit (2000) p. 19; Cokayne; White (1953) p. 383; Kingsford (1915) p. 74.

Sources

Sources primaires

- Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland, vol. Vol. 2, A.D. 1272–1307, Édimbourg, H. M. General Register House, (lire en ligne)

- Calendar of Entries in the Papal Registers Relating to Great Britain and Ireland, vol. Vol. 1 (pt. 2), Londres, Her Majesty's Stationery Office, (lire en ligne)

- Calendar of Chancery Warrants, A.D. 1244–1326, Londres, Her Majesty's Stationery Office, (lire en ligne

)

) - Instrumenta Publica Sive Processus Super Fidelitatibus Et Homagiis Scotorum Domino Regi Angliæ Factis, A.D. MCCXCI–MCCXCVI, Édimbourg, The Bannatyne Club, (lire en ligne)

- CL Kingsford, The Grey Friars of London : Their History with the Register of Their Convent and an Appendix of Documents, Aberdeen, Aberdeen University Press, coll. « British Society of Franciscan Studies (series vol. 6) », (lire en ligne)

- Charters, Bulls and Other Documents Relating to the Abbey of Inchaffray : Chiefly From the Originals in the Charter Chest of the Earl of Kinnoull, Édimbourg, Scottish History Society, coll. « Publications of the Scottish History Society (series vol. 56) », (lire en ligne)

- CJ Neville, The Earls of Strathearn From the Twelfth to the Mid-Fourteenth Century, With an Edition of Their Written Acts, vol. Vol. 2, Université d'Aberdeen, 1983b

- « PoMS, H2/152/1 », sur People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1314, n.d. (consulté le )

- « PoMS, H6/2/0 », sur People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1314, n.d. (consulté le )

- « PoMS Transaction Factoid, No. 38476 », sur People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1314, n.d. (consulté le )

- « PoMS Transaction Factoid, No. 79965 », sur People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1314, n.d. (consulté le )

- Rotuli Scotiæ in Turri Londinensi, vol. Vol. 1, George III of the United Kingdom, (lire en ligne)

- « RPS, 1293/2/10 », sur The Records of the Parliaments of Scotland to 1707, n.d. (consulté le )

- « RPS, 1293/2/10 », sur The Records of the Parliaments of Scotland to 1707, n.d. (consulté le )

- Fœdera, Conventiones, Litteræ, Et Cujuscunque Generis Acta Publica, Inter Reges Angliæ, Et Alios Quosvis Imperatores, Reges, Pontifices, Principes, Vel Communitates, vol. Vol. 1 (pt. 2), Londres, (hdl 2027/umn.31951002098036i, lire en ligne

)

) - Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland, vol. Vol. 5, (Supplementary) A.D. 1108–1516, Archives nationales d'Écosse, n.d. (lire en ligne)

- Calendar of Documents Relating to Ireland, Preserved in Her Majesty's Public Record Office, London, 1293–1301, Londres, Longman & Co., (lire en ligne)

- The Acts of the Parliaments of Scotland, vol. Vol. 1, (hdl 2027/mdp.39015035897480, lire en ligne

)

) - Vetera Monumenta Hibernorum et Scotorum Historiam Illustrantia, Rome, Vatican, (hdl 2027/mdp.39015022391661, lire en ligne

)

) - Extracta E Variis Cronicis Scocie : From the Ancient Manuscript in the Advocates Library at Edinburgh, Édimbourg, The Abbotsford Club, (lire en ligne)

Sources secondaires

- GWS Barrow, Kingship and Unity : Scotland 1000–1306, Toronto, University of Toronto Press, (ISBN 0-8020-6448-5)

- (en) AG Beam, The Balliol Dynasty, 1210–1364, Édimbourg, John Donald, , 391 p. (ISBN 978-1-904607-73-1)

- R Brydall, « The Monumental Effigies of Scotland, From the Thirteenth to the Fifteenth Century », Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, vol. 29, 1894–1895, p. 329–410 (DOI 10.5284/1000184, lire en ligne [PDF])

- The Complete Peerage, vol. Vol. 12, part 1, Londres, The St Catherine Press,

- (en) EJ Cowan, Scotland in the Reign of Alexander III, 1249–1286, Édimbourg, John Donald, , 103–131 p. (ISBN 0-85976-218-1), « Norwegian Sunset — Scottish Dawn: Hakon IV and Alexander III »

- S Duffy, Ireland and the Irish Sea Region, 1014–1318, Trinity College, (hdl 2262/77137, lire en ligne

)

) - TF Henderson, Dictionary of National Biography, vol. Vol. 55, Londres, Smith, Elder & Co., , 35–36 p. (lire en ligne), « Strathearn, Malise »

- J Higgitt, The Murthly Hours : Devotion, Literacy and Luxury in Paris, England and the Gaelic West, Londres, The British Library, coll. « The British Library Studies in Medieval Culture », (ISBN 0-8020-4759-9)

- CT Holton, Masculine Identity in Medieval Scotland: Gender, Ethnicity, and Regionality, University of Guelph, (hdl 10214/10473, lire en ligne)

- AAB McQueen, The Origins and Development of the Scottish Parliament, 1249–1329, Université de St Andrews, (hdl 10023/6461, lire en ligne

)

) - CJ Neville, The Earls of Strathearn From the Twelfth to the Mid-Fourteenth Century, With an Edition of Their Written Acts, vol. Vol. 1, Université d'Aberdeen, 1983a

- JB Paul, « The Abernethy Pedigree », The Genealogist, vol. 18, , p. 16–325, 73–378 (lire en ligne)

- The Scots Peerage : Founded on Wood's Edition of Sir Robert Douglas's Peerage of Scotland, Containing an Historical and Genealogical Account of the Nobility of that Kingdom, vol. Vol. 8, Édimbourg, David Douglas, (lire en ligne)

- WDH Sellar, Alba : Celtic Scotland in the Middle Ages, East Linton, Tuckwell Press, , 187–218 p. (ISBN 1-86232-151-5), « Hebridean Sea Kings: The Successors of Somerled, 1164–1316 »

- WDH Sellar, « MacDougall, Ewen, Lord of Argyll (d. in or After 1268) », sur Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, (DOI 10.1093/ref:odnb/49384, consulté le )

- F Watson, Edward I in Scotland : 1296–1305, Université de Glasgow, (lire en ligne)