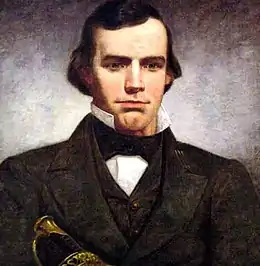

John Quincy Marr

John Quincy Marr ( - ) était un capitaine de compagnie de milice de Virginie et le premier soldat confédéré tué par un soldat de l'Union au combat pendant la guerre civile américaine. Marr a été tué lors de la bataille de Fairfax Court House, en Virginie, le 1er juin 1861. Marr s'est initialement opposé à la sécession de son État de l'Union, mais a finalement soutenu la sécession, tout comme les électeurs. Peu de temps avant son escarmouche fatale.

Jeunesse

John Q. Marr estné le à Warrenton , dans le comté de Fauquier, en Virginie . Il était le fils de Catherine Inman Horner Marr (1797-1879) et John Marr, Esq. (1788-1848), qui s'était marié en 1816. L'aîné John Marr était le petit-fils d'un immigrant français du nom de "La Mar". L'aîné John Marr avait été commissaire de chancellerie aux cours suprêmes et de comté, un peu comme un administrateur nommé par le tribunal à une époque ultérieure, ainsi que juge de paix[1]. Il posséder des esclaves noirs[2], comme le feraient sa veuve et son fils John Q. Marr en 1860[3].

John Quincy Marr est diplômé deuxième de la classe de 1846 du Virginia Military Institute (VMI)[4]. Cependant, son père est mort le 3 juin 1848, et son frère aîné Robert Athelstan Marr (1823-1854) était un officier de marine[5]. Bien que John Q. Marr ait enseigné au VMI en tant que professeur adjoint de mathématiques et de tactique après avoir obtenu son diplôme, il est rentré chez lui en 1848 pour prendre soin de sa mère et de ses sœurs Sarah / Sally (1819-1895), Margaret (1830-1903), Francis (1835-1918) et Jane (1840-1927), puisque ses jeunes frères Thomas Scott Marr (1830-1897) et James Ripon Marr (1832-1879) ont quitté la maison en 1850. Les juges locaux lui ont donné les mêmes nominations que celles détenues par son père; Marr a également servi un mandat de deux ans en tant que shérif du comté de Fauquier[6].

Route vers la guerre civile

Après le raid de John Brown sur Harpers Ferry , Marr a organisé la compagnie de milice "Warrenton Rifles"[7].

Au début de 1861, les électeurs du comté de Fauquier ont élu Marr comme délégué à la Convention de sécession de Virginie[8]. Bien qu'initialement opposé à la sécession, et appelé à la maison par une "affliction familiale" lors des délibérations, il a ensuite signé l'ordonnance de sécession[9] - [10].

Le 5 mai 1861, Marr a été nommé lieutenant-colonel dans les forces de Virginie, mais il n'a jamais reçu la commission parce qu'elle a été envoyée par erreur à Harpers Ferry[9].

Mort

Le samedi 1er juin 1861 [11], une compagnie de cavalerie de l' armée de l' Union en mission de reconnaissance est entrée dans les rues du palais de justice de Fairfax après avoir repoussé un piquet confédéré et fait un autre prisonnier. À cette époque, deux compagnies de cavalerie et la compagnie d'infanterie Marr's Warrenton Rifles occupaient la ville. La cavalerie confédérée a commencé à battre en retraite et à couper une partie des fusils Warrenton de ceux qui faisaient face à la charge de cavalerie de l'Union. Seuls une quarantaine d'hommes de la compagnie étaient en mesure de combattre les cavaliers de l'Union[9].

Le lieutenant Charles Henry Tompkins du 2e régiment de cavalerie américain a dirigé la force de l'Union composée de 50 à 86 hommes [12] qui se sont séparés en deux groupes pendant qu'ils traversaient le village. Le capitaine Marr a lancé un défi aux cavaliers en leur demandant: "De quelle cavalerie s'agit-il?" Ce furent ses derniers mots. Des coups de feu dispersés ont été tirés alors que la cavalerie de l'Union passait et que le capitaine Marr était mort[9]. Marr n'était en présence immédiate d'aucun de ses hommes par une nuit noire si peu de temps après sa chute, personne ne savait où il était ni ce qui lui était arrivé[13]. Son corps a été retrouvé plus tard dans la matinée[14] - [15].

Après la chute de Marr, est apparu pour la première fois l'ancien gouverneur de Virginie , puis le général de division William "Extra Billy" Smith , qui venait de démissionner de son siège au Congrès américain . Il était de Warrenton et avait aidé à élever l'entreprise. Il a pris le commandement en l'absence des dirigeants de l'entreprise. Peu après, le lieutenant-colonel (plus tard lieutenant-général ) Richard S. Ewell, qui venait d'être placé à la tête des forces confédérées au palais de justice de Fairfax, est tombé sur l'entreprise. Le lieutenant-colonel Ewell avait reçu une blessure à l'épaule en sortant de l'hôtel du village alors que les forces de l'Union traversaient les rues pour la première fois, il saignait alors qu'il prenait en charge la compagnie d'infanterie sur le terrain et en redéployait 40 d'entre eux[16]. Ewell partit bientôt pour envoyer des renforts et Smith redéploya les hommes à nouveau dans la même zone générale mais dans une position moins exposée à environ 100 mètres en avant[17]. Après que la cavalerie d'Union ait traversé le village, ils se sont regroupés et sont revenus par les rues du village. Une volée des hommes redéployés des Warrenton Rifles les fit reculer[18]. Les Confédérés ont tiré des volées supplémentaires sur les Fédéraux alors qu'ils tentaient de traverser à nouveau la ville sur le chemin du retour vers leur base près de Falls Church, en Virginie[18] . Après une troisième tentative infructueuse de passer devant les Confédérés, les hommes de l'Union ont été forcés de quitter la ville vers Flint Hill dans la région d'Oakton du comté de Fairfax au nord de la ville de Fairfax avec plusieurs hommes blessés[19].

Les victimes confédérées de l'affaire ont fait un mort, quatre blessés (dont le lieutenant-colonel Ewell) et un disparu, selon leur rapport[14]. Un compte rendu ultérieur déclare que seulement deux ont été blessés, mais cinq ont été capturés[20]. La force de l'Union a perdu un tué, quatre blessés (dont le lieutenant Tompkins) et trois disparus, qui avaient été faits prisonniers. Le soldat de l'Union tué a été identifié comme étant le soldat Saintclair[21]. Le gouverneur Smith a rapporté plus tard que Marr avait apparemment été touché par une balle ronde usée parce qu'il avait une large ecchymose au-dessus de son cœur mais que sa peau n'avait pas été pénétrée[22].

Conséquences

Le corps du capitaine Marr est arrivé à Warrenton ce soir-là. L'après-midi suivant, une foule nombreuse a assisté à une cérémonie dans la cour du bureau du greffier avant son inhumation au cimetière de Warrenton[14] - [23] - [24].

Charles Henry Tompkins a reçu la médaille d'honneur pour ses actions lors de la bataille de Fairfax Court House (juin 1861) . Il s'agissait de la première action d'un officier de l'armée de l'Union durant la guerre civile américaine pour laquelle une médaille d'honneur a été décernée, bien qu'elle n'ait été décernée qu'en 1893[25] - [26]. Sa citation se lit comme suit: "Deux fois chargés à travers les lignes ennemies et , prenant une carabine d'un homme enrôlé, a tiré sur le capitaine de l'ennemi. " [27] Aucun autre compte référencé sur cette page n'indique que Tompkins a personnellement tiré sur le capitaine Marr[28].

Un monument au capitaine Marr a été érigé le 1er juin 1904 près de la façade du palais de justice où il se trouve encore aujourd'hui. Il se lit comme suit: "Cette pierre marque le théâtre du début du conflit de la guerre de 1861-1865, lorsque John Q. Marr, capitaine des Warrenton Rifles, qui fut le premier soldat tué au combat, tomba à 800 pieds au sud, 46 degrés ouest. du lieu. 1er juin 1861. Érigé par le camp Marr, CV, 1er juin 1904. "[18]

Décès plus tard du soldat Henry L. Wyatt

De nombreux auteurs ont déclaré que le soldat Henry L. Wyatt du 1st North Carolina Volunteers, plus tard le 11th North Carolina Infantry Regiment, le seul soldat confédéré tué à la bataille de Big Bethel, en Virginie, le 10 juin 1861, était le premier soldat confédéré tué en combat dans la guerre civile. Cela n'est vrai que dans la mesure où une distinction est faite entre le premier officier tué, le capitaine John Quincy Marr, et le premier enrôlé tué, ce que semble avoir été le soldat Wyatt[29].

Notes et références

- (en) Cet article est partiellement ou en totalité issu de l’article de Wikipédia en anglais intitulé « John Quincy Marr » (voir la liste des auteurs).

- Walker, Charles D. Memorial, Virginia Military Institute: Biographical sketches of the Graduates and Eleves of the Virginia Military Institute Who Fell in the War Between the States. Philadelphia: J. P. Lippincott & Company, 1875. (OCLC 229174667). Retrieved May 11, 2011. p. 359–360

- 1840 U.S. Federal Census for Leeds, Fauquier County, Virginia shows John Marr as owing 6 or 7 male and 7 female black slaves. The 1850 U.S. Federal census slave schedules for the family may have been misdigitized or missing.

- Virginia's 1860 slave schedules for both Catherine "J" Marr and John "D" Marr of Fauquier County are referenced by ancestry.com, but not available online. The 1860 U.S. Federal Census for the Southwest Revenue District of Fauquier County shows Catherine as owning a 17 year old male and 45 and 19 year old female black slaves. The corresponding 1860 federal census slave schedule for John Q. Marr may have been misdigitized or missing.

- At least one account says Marr was first in the class.

- findagrave numbers 46877736, 154382252. However the elder John Marr's death is listed as occurring in 1846. Their marriage record is not available at ancestry.com, likewise the probate record, and Virginia began compiling death records decades later. Fauquier may have been one of the counties to send its court records to Richmond, where they were burned during the Confederate Evacuation Fire of April 1865

- Walker, 1875, p. 361

- Captain Marr's company, the Warrenton Rifles, was still a unit of the "Virginia Army," even though the secession of Virginia was ratified by a popular vote on May 23, 1861. Governor John Letcher issued a proclamation transferring Virginia forces to the Confederacy on June 6, 1861 and Major General Robert E. Lee, commanding state forces, issued an order in compliance with the proclamation on June 8, 1861. United States. War Dept, Robert Nicholson Scott, et al. The War of the Rebellion: a compilation of the official records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I, Volume II. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1880. (OCLC 427057). Retrieved May 14, 2011. p. 911–912. The company became Company K of the 17th Virginia Infantry Regiment when that regiment was organized on June 10, 1861. Wise, 1870, p. 17. The forces at Fairfax Court House were under the command of Lt. Col. Richard S. Ewell of the Provisional Army of the Confederate States. Even before the popular vote on secession in Virginia, the State had agreed that its separate force would cooperate with the Confederacy.

- Walker, 1875, p. 360–361

- Walker, 1875, p. 363

- All but one of the accounts that mention Marr's marital status say that he was unmarried or do not mention this aspect of his personal life. Poland Jr., Charles P. The Glories Of War: Small Battle And Early Heroes Of 1861. Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse, 2006. (ISBN 1-4184-5973-9). p. 42–43 says Marr had a wife and six children and a Cherokee mistress named Eliz Nickens with whom he had six more children. He also says that Marr had been mayor of Warrenton. None of the other references for this page confirm these details. Poland's detailed account relies at least in part on a private letter in the Warrenton Public Library for these personal details.

- The report of the Confederate adjutant general for the year ending September 30, 1862 notes the death of Captain Marr but gives the date as May 31, 1861. This can be reconciled in that the Union force left their base at 10:30 p.m. on May 31 and the battle took place on the "night" of May 31, albeit in the early morning hours of June 1, 1861. The entry in the report also states: first blood of the war. Walker, 1875, p. 366

- Walker, 1875, p. 363 says Tompkins had 86 men. Poland Jr., 2006, p. 37, says there were about 50 men in the patrol; he says that Tompkins reported he had 51 men, although he notes that General Irvin McDowell reported that Tompkins had 75, Poland Jr., 2006, p. 82. Longacre, Edward G. Lincoln's Cavalrymen: A History of the Mounted Forces of the Army of the Potomac. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2000. (ISBN 0-8117-1049-1). p. 18 uses the number of 75 men from McDowell's report for the size of Tompkins's force.

- Wise, George. History of the Seventeenth Virginia Infantry, C. S. A.. Baltimore: Kelly, Piet and Company, 1870. (OCLC 1514671). Retrieved May 13, 2011. p. 18

- Walker, 1875, p. 364

- Donald Pfanz in Richard S. Ewell: a Soldier's Life, states that Lt. Col. Ewell challenged the riders with similar words, out of concern that they might be the Confederate horsemen, and was answered with a pistol shot which wounded his shoulder. Pfanz, Donald C. Richard S. Ewell: A Soldier's Life. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998. (ISBN 0-8078-2389-9). p. 127. Other accounts of his wounding state that Ewell was wounded as he emerged from the hotel to find the Warrenton Rifles.

- As noted earlier, Pfanz, 1998, p. 127 states that Ewell was wounded after he took charge of the Warrenton Rifles. Walker, 1875, p. 364 says that Ewell received a wound in the shoulder at the beginning of the fight.

- Pfanz says that Ewell deployed the men behind stone walls. Pfanz, 1998, p. 127

- Poland, 2006, p. 82

- Wise. 1870, p. 19

- Poland, 2006, p. 40

- Moore, ed., Frank. The Rebellion Record: A Diary of American Events. 11 volumes. Volume 1, p. 321–322. New York: G.P. Putnam, D. Van Nostrand, 1861–1863; 1864–68. (OCLC 2230865). Retrieved May 13, 2011

- Poland, 2006, p. 42

- Sifakis, Stewart. Who Was Who in the Civil War, p. 433. New York: Facts On File, 1988. (ISBN 0-8160-1055-2). "In a little remembered action at Fairfax Court House, Virginia, John Q. Marr was the only fatality, becoming the first martyr of the Confederacy to die in combat."

- A "Captain" Stephen Roberts, sometimes mistakenly identified as Christian Roberts, is mentioned in a few accounts as the first "armed Confederate officer" killed in the Civil War. He was killed by a small patrol of the Union 2d Virginia (U.S.) Infantry Regiment (later the 5th West Virginia Cavalry Regiment) led by Lt. Oliver R. West at Glover's Gap, Virginia (later West Virginia) on May 28, 1861. West and six men were sent to arrest certain local rebels who were suspected of cutting telegraph wires and tearing up railroad tracks about midway between Wheeling and Grafton, Virginia. Although Roberts was a local secessionist leader and his "company" intended to join the Confederate forces within a few days, the more detailed and convincing accounts (and the ones that got Roberts's first name right) state that he was not a regularly enrolled or mustered in officer but in effect was a freelance secessionist militiaman at the time of his death. They say his men disbanded thereafter. Leib, Charles. Nine months in the quartermaster's department: or, The chances for making a Million. Cincinnati: Moore, Wilstach, Keys & Co., 1862. (OCLC 1113021) Retrieved May 20, 2011. p. 11; Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, May 30, 1861. It appears that Roberts, like Jackson, must be considered a civilian at the time of his death.

- Longacre, Edward G. Lincoln's Cavalrymen: A History of the Mounted Forces of the Army of the Potomac. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2000. (ISBN 0-8117-1049-1). p. 19

- Private Francis E. Brownell was awarded the Medal of Honor for his action in killing James W. Jackson (middle initial sometimes given as "T"), the man who had just killed Colonel Elmer E. Ellsworth at Alexandria, Virginia on May 24, 1861. His award also was received considerably later, in 1877. His was the first action for which the Medal of Honor was awarded. Sifakis, 1988, p. 81

- « Medal of Honor recipients Civil War (M-Z) » [archive du ], United States Army Center of Military History (consulté le )

- Poland, 2006, p. 83 says that a rumor began to circulate that Marr had been shot by his own men but that the consensus became that he was killed by a stray shot from a Union trooper. Governor Smith agreed with this view. Longacre, 2000, p. 19–20 and Pfanz, 1998, p. 128 also give the stray shot account.

- Norris, David. The Battle of Big Bethel p. 226–227 In Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History, edited by David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000. (ISBN 0-393-04758-X)

Bibliographie

- Leib, Charles. Nine months in the quartermaster's department: or, The chances for making a Million. Cincinnati: Moore, Wilstach, Keys & Co., 1862. (OCLC 1113021) Retrieved May 20, 2011.

- Longacre, Edward G. Lincoln's Cavalrymen: A History of the Mounted Forces of the Army of the Potomac. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2000. (ISBN 0-8117-1049-1).

- Moore, ed., Frank. The Rebellion Record: A Diary of American Events. 11 volumes. New York: G.P. Putnam, D. Van Nostrand, 1861–1863; 1864–68. (OCLC 2230865). Retrieved May 13, 2011.

- Norris, David. The Battle of Big Bethel p. 226–227 in Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History, edited by David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000. (ISBN 0-393-04758-X).

- Pfanz, Donald C. Richard S. Ewell: A Soldier's Life. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998. (ISBN 0-8078-2389-9).

- Poland Jr., Charles P. The Glories Of War: Small Battle And Early Heroes Of 1861. Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse, 2006. (ISBN 1-4184-5973-9).

- Sifakis, Stewart. Who Was Who in the Civil War. New York: Facts On File, 1988. (ISBN 0-8160-1055-2).

- United States. War Dept, Robert Nicholson Scott, et al. The War of the Rebellion: a compilation of the official records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I, Volume II. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1880. (OCLC 427057). Retrieved May 14, 2011.

- Walker, Charles D. Memorial, Virginia Military Institute: Biographical sketches of the Graduates and Eleves of the Virginia Military Institute Who Fell in the War Between the States. Philadelphia: J. P. Lippincott & Company, 1875. (OCLC 229174667). Retrieved May 11, 2011.

- Wise, George. History of the Seventeenth Virginia Infantry, C. S. A.. Baltimore: Kelly, Piet and Company, 1870. (OCLC 1514671). Retrieved May 13, 2011.